Human Ancestors Were Already Bipeds 7-Million Years Ago

It took millions of years for modern humans to evolve from apelike creatures to today’s Homo sapiens, ie. you and me. At various points along this long and arduous journey certain important milestones were reached, and one of the most significant was the time when archaic humans began walking on two legs rather than four, making them (us) upright-walking bipeds. Because this adaptation was so important, evolutionary scientists have been striving for decades to discover exactly when this vital change took place.

This has not been an easy challenge, since well-preserved fossils of ancient humans and related species are so difficult to find. But a new analysis just published in the journal Nature contends that the switch from quadrupedal to bipedal locomotion in early humans occurred approximately seven million years ago, or one million years earlier than previously believed.

This conclusion is based on a detailed study of thigh (femur) and forearm (ulna) fossils recovered during excavations in the African country of Chad, in 2001. The fossilized bones came from a hominin species identified as Sahelanthropus tchadensis, an extinct primate that lived in North Africa during the Miocene epoch.

This species was unknown before its discovery at the Chad-based desert site known as Toros-Menalla, and if the scientists responsible for the study discussed in Nature are right, it was the first human ancestor to walk upright on the African continent.

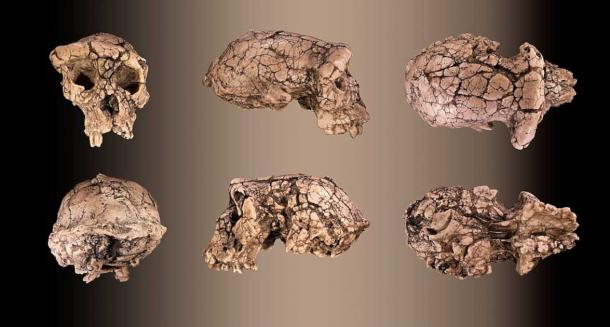

An analysis of 3-D models of approximately 7-million-year-old fossils from Chad, Africa indicate that this individual was a biped or walked upright on two feet. An upper leg bone seen from two angles, far left, and two forearm bones, each also shown from two. (Franck Guy / PALEVOPRIM / CNRS – University of Poitiers)

Finding the Missing Bipedalism Link

In this new research project, scientists affiliated with the paleontology department at the University of Poitiers in France teamed with colleagues from the University of N'Djamena in Chad, Africa to perform a fresh comparative analysis of fossils that were originally discovered more than two decades ago. For the purposes of this study, they compared the Sahelanthropus tchadensis thigh and forearm bones to the same bones taken from chimpanzees, gorillas, and modern humans.

They already knew about the locomotion patterns and physiological characteristics of these other creatures, so they were able to draw conclusions about how Sahelanthropus tchadensis would have moved based on its similarities and differences.

The scientists examined the fossils seeking data about 20 different traits that would help determine whether or not Sahelanthropus tchadensis could walk on two legs. They looked at both the outer shape of the fossils and its internal characteristics, the latter of which were accessed through microtomographic imaging technology. They concluded that the structure of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis fossils were most consistent with a species that would normally walk around on two feet, despite preserving the tree-climbing ability of some of their ancestors.

- Lost in the Mists of Time: The Ancient Sao Civilization in Central Africa

- Did Ancient Humans Acquire Nautical Knowledge by Sailing the Prehistoric Megalakes of Africa?

It was the bones’ “total pattern of features” and not a single “magic trait” that led the research team to conclude that Sahelanthropus tchadensis was bipedal, University of Poitiers paleoanthropologist and study lead author Franck Guy told Science.

If this determination is correct it means there was a species of archaic human walking upright on two legs through the forests surrounding prehistoric Lake Chad at least one million years earlier than either Orrogin tugensis or Ardipithecus, two human ancestors that had been previously identified as the first to make the transition to bipedal locomotion.

Interestingly, even though they were still climbing trees Sahelanthropus tchadensis didn’t do it in quite the same way as some of their primate cousins.

While gorillas and chimpanzees climb trees with their fingers, Sahelanthropus tchadensis was able to scamper upward from branch to branch using a firm hand grip (the same way modern humans climb trees today).

"The curvature and cross-sectional geometric properties of the ulna… are indicative of habitual arboreal behaviors, including climbing and/or 'cautious climbing', rather than terrestrial quadrupedalism,” the researchers explained in their Nature paper.

The type of evolutionary change discovered in this case is indicative of a species in transition. Sahelanthropus tchadensis had not entirely abandoned the old ways, even though they could move about efficiently in an upright position.

The Toumaï skull, found in Chad, Africa, viewed from different angles, which had already suggested that this species was highly advanced and likely could walk upright on two legs, but without the scientific evidence to prove the very claim made in the recent scientific study. (Didier Descouens / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Evolution Works its Magic

In the 2002 study that first introduced Sahelanthropus tchadensis to the world, scientists examined a skull from the species that was recovered at the same site as the thigh and forearm bones. Certain characteristics of this skeletal artifact suggested that these apelike human ancestors could walk on two legs, but more evidence was needed to confirm this startling hypothesis—evidence that has apparently now been discovered.

It was already known that modern humans split from the evolutionary lines of chimpanzees between six and eight million years ago, when Sahelanthropus tchadensis literally walked the earth. The change to bipedal locomotion can now been seen as one of the adaptations that helped cause this divergence.

These early human ancestors resided in a Miocene epoch environment that featured a mixture of forests, palm groves, and grasslands. Being able to walk on two feet while still easily climbing trees would have allowed them to navigate each section of this complex ecosystem successfully, giving them the ability to secure all the food they would have needed to survive.

Two arm bones and a leg bone belonging to Sahelanthropus tchadensis subjected to microtomographic imaging technology scanning. (Franck Guy / PALEVOPRIM / CNRS – University of Poitiers)

A Controversy Ensues

Despite being identified as having come from Sahelanthropus tchadensis back in 2004, the thigh and femur bone remained unstudied until 2017. That’s when Franck Guy and his University of Poitiers associate Guillaume Daver began looking at the bones in earnest, trying to learn more about how Sahelanthropus tchadensis lived and moved. They eventually recruited more specialists to assist them in their analysis, which allowed them to perform the extensive list of tests that apparently demonstrated the newly discovered human ancestor’s bipedal capacities.

It must be noted, however, that the claim made by Guy, Daver, and their team members has not been universally accepted within the scientific community. In fact, their conclusions are being met with quite a bit of skepticism at the moment.

Multiple scientists contacted by Science expressed their doubts that the researchers had achieved any kind of important breakthrough.

- Cretan Footprints Challenge Darwin’s Out of Africa Theory, Says Study

- The Widespread Appearance of Neanderthal DNA: Africans Have It Too

“The evidence is compatible with bipedality” but does not prove it, functional morphologist Chris Ruff of Johns Hopkins University said in the Science article. Paleoanthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri, Columbia acknowledged that “any fossils that speak to this are really important,” but added that “these don’t provide the conclusive information we hoped for.”

Naturally, the University of Poitiers and University of N'Djamena researchers respectfully disagree.

"The most parsimonious hypothesis remains that the postcranial morphology of Sahelanthropus is indicative of bipedality, and that any other hypothesis would have less explanatory power for the set of features presented by the material from Chad," stated the scientists in their Nature paper.

This may eventually become the consensus conclusion. But at least for now, it is clear that the debate about the origin of two-legged locomotion in humans is far from settled.

Top image: Representation of the modes of locomotion practiced by Sahelanthropus in Chad, Africa 7 million years ago, which is one million years earlier than current biped origins. (Sabine Riffaut, Guillaume Daver, Franck Guy / PALEVOPRIM / CNRS – University of Poitiers)

By Nathan Falde

Comments

Evolution is at very best, a hypothesis.