When In Rome: Legends - Fact Or Fiction, Does It Matter?

The Greeks exhibited an amazing aptitude for fashioning myths about gods and heroes. Not so the Romans, who failed to produce an independent mythological tradition. But what the Romans did excel at was in shaping legends about the men and women who were instrumental in giving their city its distinctive character in the first centuries of its existence.

Many scholars eschew the word ‘legend’ altogether and prefer to classify as ‘myth’ any story told over the course of several generations that has significance for the community as a whole. By this definition, whereas a myth is a story set in the remote past, in an imaginary era when the world was still in its infancy and when gods and humans were in direct and regular contact with one another, a legend is set squarely in human history, irrespective of whether it is historical or fabricated. Most of Rome’s legends recounted would have been regarded as historical by the Romans. Any visitor to Rome in the first century BC, asking any inhabitant a related question, would have been pointed to the tree where the basket containing the twins Romulus and Remus washed up, the cave where the she-wolf later nurtured them, and the hut where the boys grew up under the care of their adoptive parents.

Romulus and Remus being cared for by a wolf, the god of the Tiber river sitting on his urn, a woodpecker that brought them food, and a shepherd discovering the infants, by Peter Paul Rubens (1615) Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome (Public Domain)

Invented Legends of Rome

It is indisputable, however, that many of Rome’s legends were invented or at least partly invented. Romulus, believed to have been the son of Mars, is clearly a mythical figure, though some present-day historians give credence to the deeds attributed to him. The life and deeds of the six kings who succeeded Romulus should also be treated with caution, though it seems likely that a period of kingship preceded the Republic, since an inscription found in the Forum contains the word rex or king, albeit followed by the limiting noun sacrorum in the genitive case, meaning ‘in relation to sacred affairs’.

Some etiological legends may have been invented to explain obscure customs or traditions. An example is Horatius Cocles’ jump from the Sublician Bridge into the River Tiber, which recalls the tradition of throwing straw puppets from the bridge at a festival known as the Argei.

Like this Preview and want to read on? You can! JOIN US THERE ( with easy, instant access ) and see what you’re missing!! All Premium articles are available in full, with immediate access.

For the price of a cup of coffee, you get this and all the other great benefits at Ancient Origins Premium. And - each time you support AO Premium, you support independent thought and writing.

Based on an extract from Roman Legends Brought to Life Pen and Sword.

Dr Robert Garland obtained his M.A. in Classics from McMaster University and his Ph.D. in Ancient History from University College London. His research focuses on the social, religious, political, and cultural history of both Greece and Rome. He has written 17 books including Roman Legends Brought to Life

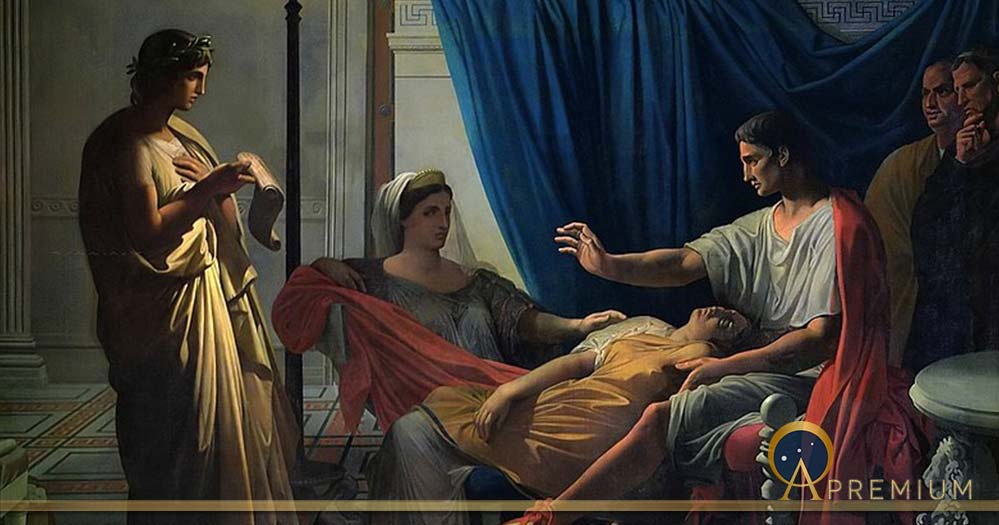

Top Image: Virgil reading The Aeneid before Augustus, Livia and Octavia, by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1812) Toulouse, Musée des Augustins (Public Domain)

By: Robert Garland