Builders of Stonehenge Feasted On Parasites Shows Prehistoric Poop Study

A new study published in the journal Parasitology analyzed prehistoric Stonehenge feces from Durrington Walls, a Neolithic settlement just 2.8 kilometers (1.7 miles) from Stonehenge and found that it contained parasitic worm eggs.

The researchers studied 19 coprolites or Stonehenge poop and found five, 1 human and 4 canine, to be full of parasitic worm eggs. The coprolites were taken from a midden (a rubbish and dung heap) in Durrington Walls. This suggests that the inhabitants ate undercooked or raw cow offal and fed their leftovers to their dogs. The site dates to 2500 BC, the period when most of the megaliths were erected at Stonehenge and is believed to have seasonally housed the builders of the famous stone monument.

According to the press release by the research team, it is the earliest evidence for parasitic infection found in the UK where the host species that produced the feces has also been identified. “This is the first time intestinal parasites have been recovered from Neolithic Britain, and to find them in the environment of Stonehenge is really something. The type of parasites we find are compatible with previous evidence for winter feasting on animals during the building of Stonehenge,” said lead author Piers Mitchell from the Department of Archaeology at Cambridge University.

Fragments of the human coprolite or Stonehenge feces sample number DW11465 used in the study. (Lisa-Marie Shillito /Parasitology)

Stonehenge Poop and the Six-stage Construction of Stonehenge

The Stonehenge prehistoric stone circle and cemetery, a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1986, was built in six stages from 3000 to 1320 BC, during the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. It is unique as a prehistoric stone circle because of its artificially shaped Sarsen stones that are arranged in a post-and-lintel formation. The stones were fashioned with mortise and tenon joints to hold the lintels in place.

- Natural Harmony: How did the Stonehenge Druids Measure the Landscape?

- Fifteen previously unknown monuments discovered underground in Stonehenge landscape

Although its purpose can only be speculated upon, it was likely a religious site and an expression of the power of the chieftains and priests who had it built and were buried in the nearby barrows. It was aligned with the sun and could have been used to observe the movement of the sun and the moon and chalk out a farming timetable. It could also have been a site for ancestor worship or perhaps druidical rituals.

It is around 2500 BC, or the second stage of its building, that the famous trilithons of Stonehenge, two gigantic vertical rocks supporting a horizontal one, were raised. These dates correspond with the habitation of Durrington Walls, most likely on a seasonal basis.

The builders of the iconic monument probably resided at Durrington Walls and feasted there, as pottery and a huge number of animal bones found at the site show. No such evidence of habitation and feasting has been recovered at the Stonehenge monument itself.

Earlier isotopic analyses of cow teeth from Durrington Walls indicated that some of the cattle had been brought there from Devon or Wales, as much as 100 kilometers (62 miles) away, for large-scale feasting. The cut marks on cattle bones from the site, meanwhile, suggested that beef was primarily chopped for stewing, and bone marrow was extracted.

It was while excavating the main midden at Durrington Walls that pottery and stone tools as well as 38,000 animal bones were found. Some 90 per cent of these bones were from pigs while the remaining belonged to cows. This is also where archaeologists recovered the coprolites or Stonehenge feces used in the study.

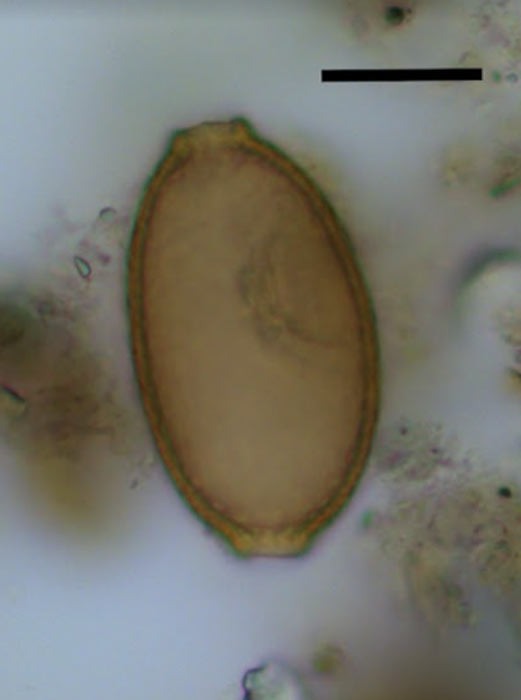

A parasitic capillariid egg from coprolite DW12164 at Durrington Walls. (Parasitology)

How the Stonehenge Poop Study Revealed New Dietary Evidence

The Stonehenge poop samples were tested for sterols and bile acids at the National Environment Isotope Facility at the University of Bristol to ascertain whether they were from humans or animals.

Four of the coprolites, including the human one, were found to be infected with the lemon-shaped eggs of capillariid worms. Capillariid worm types, all parasites, infect many animal species all over the world. However, when the European capillariid species infects animals, the eggs get deposited in the liver, which is a cow part that is still consumed today.

- Durrington Shafts: Is Britain’s Largest Prehistoric Monument a Sonic Temple?

- Feeding Stonehenge: Hearty Menu for Monument Builders Revealed - Barbeque Pork, Roast Beef, Yogurt and Cheeses

That the human coprolite contained capillariid eggs meant that the person had consumed raw or undercooked lung or liver from an infected animal, resulting in the eggs passing directly into their poop. “As capillariid worms can infect cattle and other ruminants, it seems that cows may have been the most likely source of the parasite eggs,” said Mitchell.

Co-author Evilena Anastasiou added, “Finding the eggs of capillariid worms in both human and dog coprolites indicates that the people had been eating the internal organs of infected animals, and also fed the leftovers to their dogs.”

One of the dog coprolites was found to be infected with the eggs of fish tapeworm, showing that it had eaten raw freshwater fish. But since no evidence of fish bones were found at the site, it was concluded that it had come to the site carrying the infection. The fish tapeworm clearly indicates that the inhabitants of Durrington Walls ate fish. Current research indicates that the people who lived and worked at Durrington Walls likely came from places in southern Britain.

The latest study tells us something new about the diets of the people building Stonehenge as we slowly understand more about this incredible Neolithic-Bronze Age monument.

Top image: A new study has clearly revealed new information about the people who built Stonehenge (left image) by analyzing their Stonehenge feces! The image on the right shows a parasitic capillariid worm egg found in Stonehenge poop at Durrington Walls. Source: Left: Adam Stanford; Right: Evilena Anastasiou / Parasitology

By Sahir Pandey

References

Mitchell, P.D. et al. 2022. Intestinal parasites in the Neolithic population who built Stonehenge (Durrington Walls, 2500 BCE). Parasitology. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182022000476

Comments

Interesting, sort of. Paracites are normally species specific. Not always though. Some require two different species for a life cycle, like liver flukes. A snail and and a mammal. None the less it's interesting to know today's common paracites have been around for a very long time, and it's a good idea to cook food today too.