England’s Oldest Known Shipwreck Found, With A Morbid Cargo

A wreck hunter in England has discovered a rare 13th century ship, the oldest shipwreck known in English waters. Onboard her well-preserved hull, buried among a collection of valuable marble stones, divers have identified two carved-crosses which have already changed what medieval historians previously thought about such symbols.

Poole Bay is in the English Channel on the coast of Dorset in southern England. It was on the edge of the bay’s Swash Channel that local charter boat skipper Trevor Small of Rocket Charters discovered a wrecked 13th century ship. After gaining permission to dive the site to check it out, he reported its location to Bournemouth University who have performed an underwater archaeological investigation.

With its ancient cargo encased in a thick sea-crust, archaeologists from Bournemouth University have been able to investigate the ship and its contents. The researchers say this is the “earliest” shipwreck site ever discovered where the vessel has an intact hull. What’s more, among the cargo, two decorated gravestones are already changing how historians interpret medieval cross-symbols.

Tale of the Clinker Hunter

In a report released by Bournemouth University archaeologists Captain Trevor Small of Rocket Charters claims he has “skippered thousands of sea miles looking for shipwrecks,” sailing in and out of Poole. What this comment means, is that this discovery of a rare 13th century “Clinker” was not by chance, but by the perseverance, determination, and commitment of one person, Mr Small.

The term “Clinker” refers to a medieval shipbuilding method for larger vessels. This style of shipbuilding utilized huge overlapping strakes (hull planks) while smaller ships had shorter planks meeting end to end. Mr Small first identified the hull of the 13th century clinker in the summer of 2020. Having since obtained permission to dive the wreck site “the rest is history… I've found one of the oldest shipwrecks in England,” says Captain Small.

13th century artifacts collected from the wreck. (Bournemouth University)

Ancient Tree Rings Help Date the Oldest English Shipwreck

Tom Cousins is a marine archaeologist at Bournemouth University who in the release says, “very few 750-year-old ships have ever been discovered.” And with the ship dating back to the reign of King Henry III of England the research team say they feel “extremely lucky.” An analysis of the tree rings within the ship timbers established that they were Irish oak trees that were felled between 1242-1265 AD.

So well preserved was this so-called “mortar” ship that its cargo of Purbeck stone was fully intact. The term “mortar” refers to the ship’s cargo of stones which had been quarried on the Isle of Purbeck, Dorset in southern England. The particular type of stones discovered onboard the wreck were all ‘Purbeck Marble.’ These were quarried from limestone beds in the Upper Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous Purbeck Group and they were valued by builders across Europe because they take a high polish. In this case, most of the marble stones were destined for service in mills where they would be turned on wheels to grind grains into flour.

- Viking Camp Complete with Ship Building and Weapon Workshops Unearthed in England

- Dead Viking Dynasty Invade Scottish Neolithic Tombs

Rewriting How Gravestones Were Produced

Also discovered in the hull of the clinker was a cauldron for cooking, and two Purbeck marble gravestone slabs. Brian and Moira Gittos from the Church Monuments society said Purbeck marble gravestone slabs were widely used in the south of England, Ireland and across the continent. However, these two examples have already “re-written our understanding of” how these stones were produced, said Brian and Moira Gittos.

One of the grave slabs depicts a 13th century wheel-headed cross and the second features a cross pattée, with arms narrow at the center that flare broader at the edges. What’s new here, according to Moira Gittos, is that until this pair of gravestones were discovered, these two cross designs were believed to be part of a “developmental sequence” and not in use in the same time period.

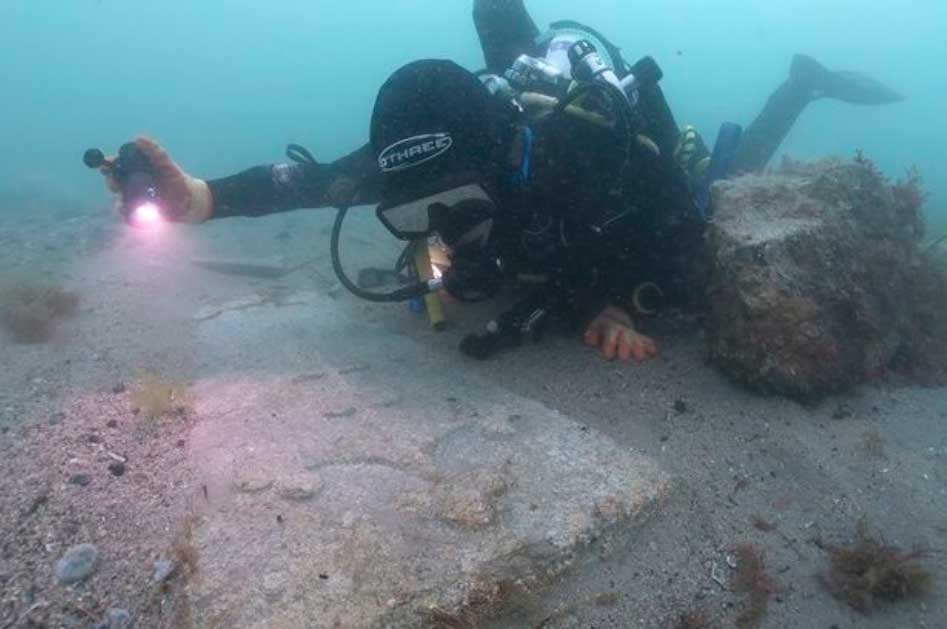

One of the two perfectly preserved Purbeck marble gravestones, in situ on the sea bed, featuring a wheel headed cross, an early 13th century style. (Bournemouth University)

Loaded Too Heavy For The Swash, Perhaps

Putting this shipwreck into historical perspective, the town of Poole was founded on a peninsula in the early 12th century by merchants from nearby Wareham. Surrounded by water on three sides the town was easy to defend but it burned to the ground in 1139 AD during the ‘Anarchy,’ a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 AD and 1153 AD.

By the early 13th century Poole had been rebuilt and thrived again as an important maritime trade and fishing port. Sometime between 1242-1265 AD, the currently nameless clinker with her cargo of millstones and gravestones, perhaps struggled to balance her heavy load as she entered the Swash Channel and capsized. Rebecca Rossiter, Engagement and Collections Manager at Poole Museum said in the University release that the wreck and her cargo will be going on display in one of Poole Museum’s three new maritime galleries when it reopens in 2024.

Top image: One of the two perfectly preserved Purbeck marble gravestones cargo of the oldest known English shipwreck, Dorset. Source: Bournemouth University

By Ashley Cowie

Comments

Interesting. Strange gravestones. No doubt even older wrecks lie waiting discovery.

Probably just ballast stones. If they were cargo, for commerce, then the stones would have to be replaced with something else as heavy. Lead was often used. Big wooden ships do require a lot of weight down in the lower holds for stability. And if not for ballast, you wouldn’t want to have to the heaviest (difficult to load/unload) cargo way down in there, which would take a lot of man-power (with pulleys and such) to haul in and out. So maybe the grave stone theory (like many theories!) needs a rethink.

Nobody gets paid to tell the truth.