2,000-Year-Old Cooling System for Chariot Horses Unearthed at Ancient Carthage Site

In the Classical world, chariot races were the equivalent of today’s highest-profile sports and had the highest-paid athletes in history. But how did the chariot horses of North Africa cope with the searing heat? Archaeologists have now found the answer after unearthing an advanced system that cooled the horses and kept the popular races running at the Roman Circus of Carthage in Tunisia 2,000 years ago.

The circuses in Carthage, Rome and elsewhere around the empire were built specifically for the chariot races, which were fast, violent and wildly popular. Haaretz, which has a report on the horse-cooling features recently discovered, says one charioteer won 36 million sesterces (silver coins) —the equivalent of about $15 billion in today’s money.

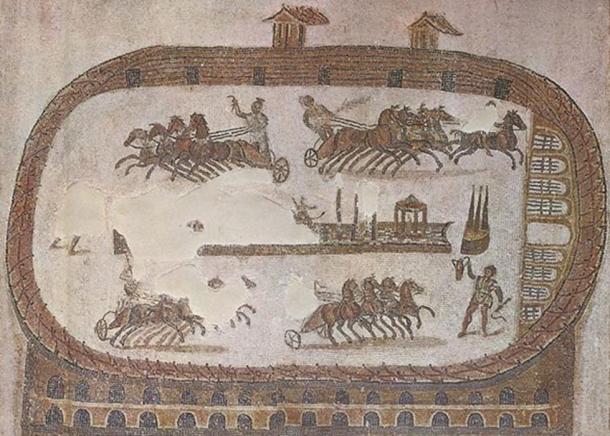

An ancient mosaic shows the circus of Carthage. (Wikimedia Commons/University of Chicago)

Carthage’s circus was 470 meters (1542 feet) long and 30 meters (98.4 feet) wide. This was smaller than the Circus Maximus in Rome, which was wider and 80 meters longer. And while the Circus Maximus could seat 150,000 to 200,000 people, scholars believe the Carthage circus held far fewer spectators at around 45,000. Still, the Carthage circus was the largest sporting venue of the empire except for those in Rome itself.

The arches of the ruins of the Circus Maximus in Rome—the largest chariot racetrack of them all. (Wikimedia Commons/Joris van Rooden)

There was ancient poetry about the chariot races (read one such poem here), mosaics, and of course the circuses around the empire that attest to the sport’s popularity.

Chariot drivers wore uniforms of distinct color and teams represented different groups in society, social or political, Haaretz says. According to accounts of the time, supporters applauded wildly when their favorite team took the field. Certain charioteers were so adulated that their portraits were hung in homes.

There were riots, including one at Pompeii that Roman historian Tacitus told about, when Pompeians fought with fanatics from nearby Nucreia.

Part of the reason the archaeologists determined that the ancient Carthaginians cooled the horses came with the discovery of water-resistant mortar at the circus.

“This kind of mortar is called hydraulic mortar. It's a type of waterproof lime mortar mixed with crushed and pulverized ceramics that the Romans used in hydraulic engineering,” Frerich Schön of Tübingen University told Ha’aretz. He is a water technology specialist who discovered the hydraulic mortar at the spina, or the median.

Water basins were built along the track and spina at Carthage and elsewhere. Sparsores—the people who sprinkled the horses—dipped clay vessels into the water and sprinkled it on the chariots as they passed, according to Ralf Bockmann of the German Archaeological Institute, co-director of the excavations with Hamden Ben Romdhane of the Institut National du Patrimonie de Tunisie.

The men say this was without doubt a dangerous job.

“The sparsores would usually be on foot, directly on the spina, presumably at the level of the arena, to cool down the chariot wheels driving by at high speed. How exactly the cooling was organized is not clear. But for sure, it must have been a dangerous business,” Dr. Bockmann told Haaretz.

Chariot racing was popular not just in Rome but also in Greece and the Byzantine Empire. It was less violent than the gladiatorial contests, but still, many horses and men suffered grave injuries and death in the races.

Nike rides a chariot to victory in this relief from ancient Greece; the sport was popular all over the Classical world. (Wikimedia Commons/Jastrow)

The charioteers were slaves or freedmen. They drove light chariots, which made the sport all the more dangerous. Races were run for seven laps, and up to a dozen chariots ran in them.

“Many drivers were thrown from a broken or overturned chariot,” says an article on PBS. “They could then be trampled and killed by the charging horses, or get caught in the reins and dragged to their deaths.”

Aristocrats sneered at the chariot races, thinking them childish and unremarkable. But the public was in thrall to them.

Top image: Chariot racing in ancient Rome (University of Wisconsin)

By Mark Miller