Ancient skull was drilled and harvested for medicine in the 18th century

The skull of a man who was beheaded in the 15 th century was at the center of a mystery until experts revealed the cranium was harvested to be used as medicine.

Within the crypt of Italy’s Otranto Cathedral resides an unnerving sight – the skulls and bones of some 800 men sit behind large glass panels, staring out as a commemoration of a tale of religious resistance. The dead men, alleged to have been executed by invading Ottoman Turks in 1480, are known as the “martrys of Otranto.”

Skulls and bones of ‘the Martyrs of Otranto’ stare out from behind glass panels in Otranto Cathedral, Italy. Laurent Massoptier, Wikimedia Commons

According to Discovery News, one of these skulls is unique in that it possesses 16 perfectly round holes on its top. How the holes were made, and for what purpose, confounded experts and visitors to the cathedral. However researchers were recently able to determine that the holes were trepannated – or drilled – into the skull after death as a way of harvesting the ground-up powder.

The skull was kept behind the glass and could not directly be accessed by researchers, but visual examination determined the holes were all regular, round shapes. Eight of the 16 holes were bored all the way through the skull, notes Discovery News.

Skull and bone powder was thought to treat many illnesses and diseases, such as epilepsy, paralysis or stroke. These ailments and others were believed to be caused by demons or magical influences.

A research paper on the skull has been published in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology. It details the findings of Gino Fornaciari, professor of history of medicine and paleopathology at the University of Pisa, and colleagues.

18th-century French illustration of trepanation. Public Domain

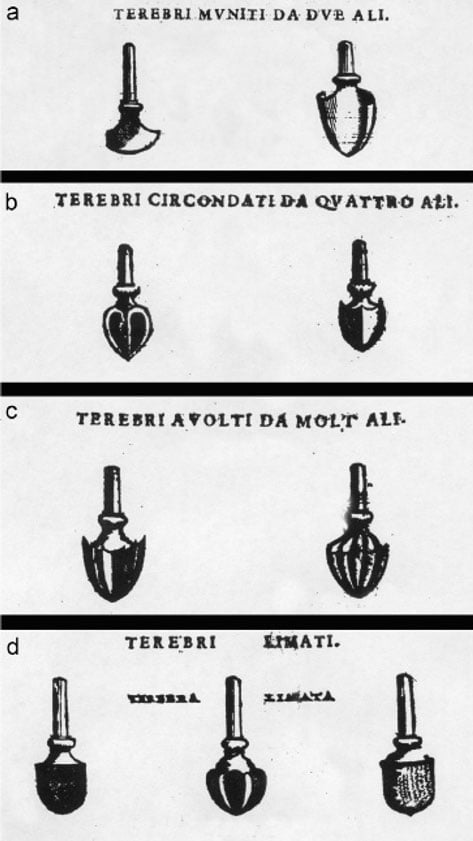

Fornaciari and colleagues surmise that the depressions and holes were drilled into the skull long after the death of the victim, and were made by a tool specifically designed to pulverize the bone into powder. He describes the tool as “a particular type of trepan, with semi-lunar shaped blade or rounded bit; a tool of this type could not produce bone discs, but only bone powder.”

Rounded drill bits used in trepanning wherein the bone is pulverized so as to collect the powder. Credit: Gino Fornaciari et al.

The skull specimen is significant. The unique evidence supports known texts and historical accounts of bone powder use in medicine. It is also of interest to the researchers due to its religious context.

The 813 ‘martyrs of Otranto’ are known as the patron saints of the Italian city of Otranto. They are said to have died on Aug. 14, 1480 after a 15-day assault on the city by an overwhelming Ottoman force. Thousands were slaughtered, and thousands more women and children were sold into slavery. Any soldiers or fighting men who lived through the siege were taken prisoner. The story goes that they were instructed to convert from Christianity to Islam. When they refused, it is said they were beheaded one by one in a mass execution, and their skulls and bones now reside in Otranto Cathedral.

Skull of ‘the Martyrs of Otranto’ in Otranto Cathedral, Italy. Andrea Marutti/Flickr

Fornaciari and colleagues theorize that as the remains were considered to be from martyrs and saints, the bones were likely regarded as having potent medicinal properties, a “powerful ingredient for pharmacological preparations.”

Valentina Giuffra, from Pisa University’s division of paleopathology and co-author of the study told Discovery News, “The head was considered the most important part of the human body. It was believed that right there invisible spiritual forces remained active even after death.”

MORE

- Mummy Brown – the 16th century paint made from ground up mummies

- 11,000-year-old site of Asikli Hoyuk in Turkey reveals early brain surgery and ancient craftsmanship

- Ancient Pazyryk nomads carried out highly advanced cranial surgery in Siberia

French chemist Nicolas Lémery (1645 –1715) wrote in his work “Pharmacopée universelle”, that powdered skull, when combined with water and swallowed, was an effective treatment for “illness of the brain,” reports LiveScience. Lémery continued, “The skull of a person who died of violent and sudden death is better than that of a man who died of a long illness or who had been taken from a cemetery: the formers has held almost all of his spirits, which in the latter they have been consumed, either by illness or by the earth.”

In the 18 th century skull powder was used as medicine to treat illnesses. This jar label represents “CRAN(IUM) HUM(A)N(UM) P(RE)P(ARA)T(UM)”. Credit: Museum of Pharmacy, Cracow

It’s not known why that particular skull was chosen out of the many to be drilled. The researchers can only suggest that the procedure took place when the skulls and bones were being carefully arranged within the glass cabinets, in 1711.

Much has been gleaned on the practice of trepanation and ancient surgery, with archaeological finds revealing trepanning surgeries performed in Siberia 2,000 years ago, leg drilling surgery in prehistoric Peru, and skull trepanation in skulls in Turkey dating back to 9000 B.C.

This historically significant holy (and holey) skull gives a rare glimpse into the world of historical medicine, and the use of human remains in pharmacological treatments.

Featured Image: Skull with multiple drill markings. Credit: Gino Fornaciari/University of Pisa

By Liz Leafloor

Comments

Do you suppose this is what the Skull and Bones have done with Geronimo's skull? Making medicine out of it?