The Book of the Dead is not a book per se, but rather, a corpus of ancient Egyptian funerary texts from the New Kingdom. Each ‘book’ is unique, as it contains its own combination of spells. In total, about 200 spells are known, and these may be divided into several themes.

In general, the spells are meant to aid the recently deceased in their journey through the underworld, which is perilous, and full of obstacles. Many of the spells have their origin in the earlier Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, which shows the continuity, as well as changes in the beliefs held by the ancient Egyptians regarding the afterlife. Although it is commonly called the Book of the Dead, its original name in ancient Egyptian is transliterated as rw nw prt m hrw, which may be translated as Book of Coming Forth by Day or Book of Emerging Forth into the Light.

Origin of the Book of the Dead

It is unclear as to when the Book of the Dead was first produced. Nevertheless, the earliest known example of this work was found on the sarcophagus of Mentuhotep, a 13th dynasty queen. Due to the presence of new spells, scholars have considered the Mentuhotep’s sarcophagus as the earliest example of the Book of the Dead that we have at present. The 13th dynasty is often considered to be part of the Middle Kingdom (though some consider it to be part of the Second Intermediate Period), during which two collections of funerary texts, the Pyramid Texts and the Coffin Texts, were being used.

The Pyramid Texts are the older of the two and were ‘written’ during the time of the Old Kingdom. Like the Book of the Dead, the Pyramid Texts are also a collection of spells. These spells were found to have been carved onto the walls and sarcophagi of the pyramids at Saqqara (hence the name of the work), which were constructed during the 5th and 6th dynasties. Unlike the later Coffin Texts and Book of the Dead, the Pyramid Texts do not contain any illustrations.

During the Old Kingdom, the Pyramid Texts were reserved for the pharaoh, and this is reflected in the spells found in this work. These spells deal mainly with the protection of the pharaoh’s physical remains, the reanimation of his body after death, and his ascension to the heavens, the three primary concerns of the Old Kingdom pharaohs regarding their afterlife.

The ultimate goal of the pharaoh was to become the sun or the new Osiris, but this journey of transformation was full of perils. Therefore, the Pyramid Texts contains spells that could be used to call upon the gods for their aid in the afterlife, a feature found in later funerary texts as well. Interestingly, if the gods refused to comply, the Pyramid Texts provides spells that the deceased pharaoh could use to threaten them.

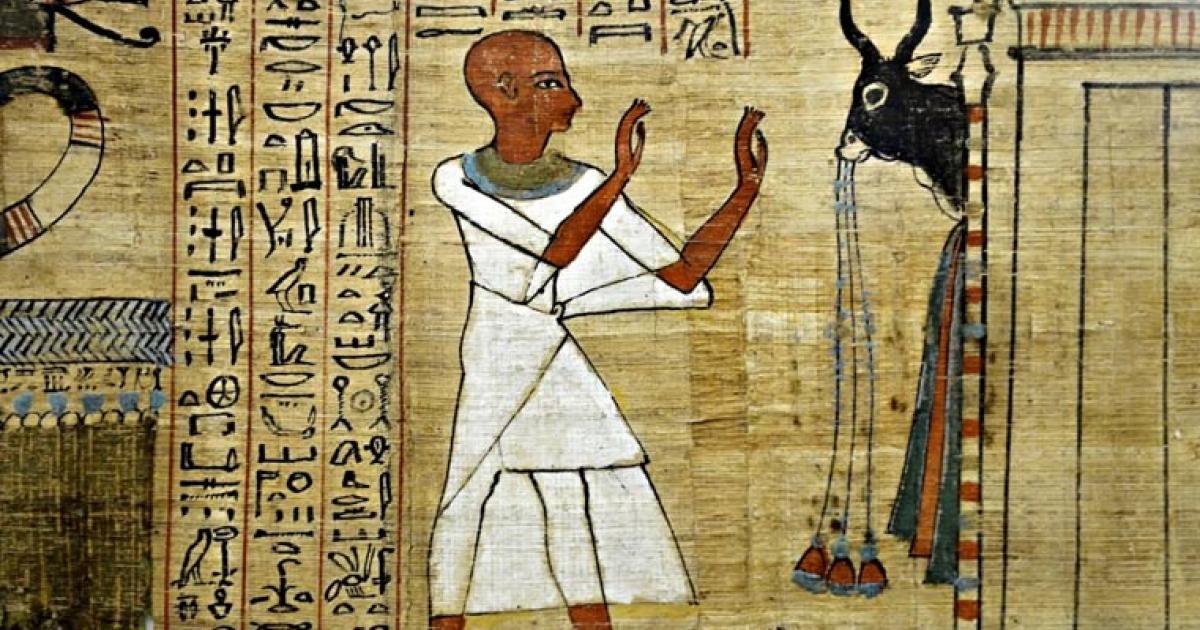

The mystical Spell 17, from the Papyrus of Ani. The vignette at the top illustrates, from left to right, the god Heh as a representation of the sea; a gateway to the realm of Osiris; the Eye of Horus; the celestial cow Mehet-Weret; and a human head rising from a coffin, guarded by the four sons of Horus. (The Land / Public Domain)

During the First Intermediate Period, the ancient Egyptians began writing spells on coffins. It was, however, only during the Middle Kingdom that it became widespread. Currently, the work known as the Coffin Texts consists of around 1,185 spells, most of which are found to have been written on coffins, hence its name.

Other places where the spells are found to have been written on include tomb walls, papyri, and stelae. The Coffin Texts reflect a change in the beliefs that the ancient Egyptians had about the afterlife. Prior to this, the afterlife seems to have been the exclusive domain of the pharaoh, since the Pyramid Texts were only found in their funerary monuments.

The Coffin Texts show that any ordinary Egyptian who could afford a coffin now had access to the afterlife as well, hence the so-called ‘democratization of the afterlife’. Although some of the material from the Pyramid Texts continued to be used, it is clear that many new spells were added as well.

These new spells were concerned with the everyday desires of the common man, and is further evidence that by this time, commoners were also given a shot at the afterlife. Unlike the Pyramid Texts, which emphasizes the pharaoh’s ascent into the heavens, the Coffin Texts focus on the journey of the deceased to Duat, the ancient Egyptian version of the underworld, which is ruled by the god Osiris. Thus, the spells of the Coffin Texts are aimed at protecting the deceased during his/her journey in the underworld, and to help him/her pass the judgment of Osiris.

- Nine Parts of the Human Soul According to the Ancient Egyptians

- Pharoah’s Little Helpers: The Shabti Funerary Statuettes of the Ancient Egyptians

- Has the Function of the Great Pyramid of Giza Finally Come to Light?

Middle Kingdom sarcophagus with Coffin Texts and a map of the underworld painted on its panels. (Jon Bodsworth / Copyrighted free use)

The Book of the Dead’s Use Becomes Widespread

As mentioned earlier, the earliest known example of the Book of the Dead is found on the sarcophagus of Queen Mentuhotep. It was, however, only during the 17th dynasty that the Book of the Dead became more widespread. By this time, it was used not only by members of the royal family, but also by courtiers and other officials.

Although the spells were typically inscribed on the linen bandages used to wrap the mummies at this point of time, they have also been found occasionally written on coffins and papyri. The development of the Book of the Dead continued during the New Kingdom. In addition, the spells were now more commonly written on papyri, and the text is often accompanied by beautiful illustrations.

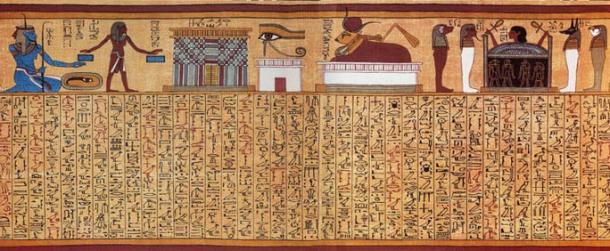

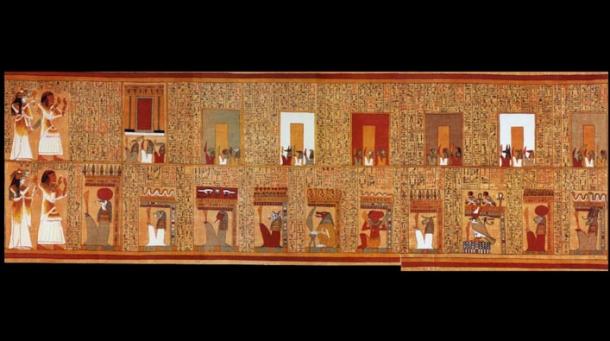

One of the most famous examples of a Book of the Dead from this period is the Papyrus of Ani, which is today displayed in the British Museum in London. The Papyrus of Ani consists of six distinct pieces of papyri and has a total length of 78 feet (23.7 meters).

Like many other examples of the Book of the Dead from the New Kingdom, the Papyrus of Ani was written in cursive hieroglyphs. Almost all of the spells on this papyrus are accompanied by an illustration, making it a beautiful work of art.

In the succeeding period, i.e. the Third Intermediate Period, the hieratic script began to be used as well. This was a cheaper version that more people could afford. The reduced cost meant that the text lacked illustrations, apart from a single one at the beginning of the work.

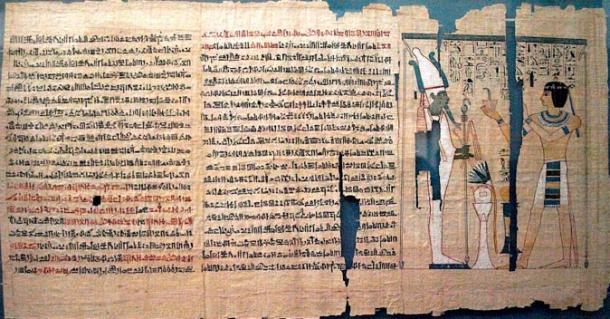

Part of the Book of the Dead of Pinedjem II. The text is hieratic, except for hieroglyphics in the vignette. (Captmondo / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Finally, it was during the 25th and 26th dynasties (the end of the Third Intermediate Period and the beginning of the Late Period) that the Book of the Dead was standardized. Thus, for the first time, the Book of the Dead obtained a coherent structure and was split into chapters. This version of the text is known as the ‘Saite Edition’ (named after the 26th or Saite dynasty), which distinguishes it from the earlier ‘Theban Edition’.

It is unclear, however, if this standardized version was the norm, since very few manuscripts can be dated with absolute certainty to the 26th dynasty. At present, there are perhaps less than 20 known copies of the Book of the Dead from this period. As a comparison, about 400-500 manuscripts from the later Ptolemaic Period are known.

The Spells of the Book of the Dead

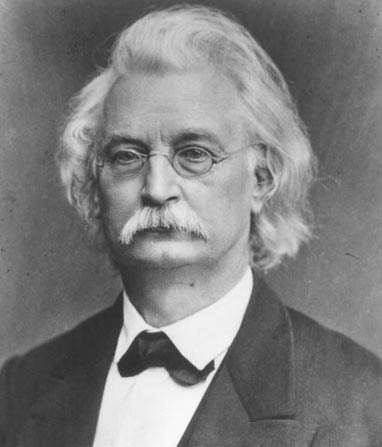

Although the spells from the Book of the Dead were already known to scholars prior to the 19th century, it was only in 1842 that the first collection of the texts were published by Karl Richard Lepsius, a German Egyptologist. It was Lepsius who coined the modern name of this text. Incidentally, the Arabs too referred to this funerary text as the Book of the Dead, alluding to the fact that they were often found accompanying mummies.

Karl Richard Lepsius, first translator of a complete Book of the Dead manuscript. (Andro96~commonswiki / Public Domain)

Apart from publishing the text, Lepsius also carefully ordered the spells, and assigned a chapter number to each of them, and this system is still in use today. Although there is no canonical Book of the Dead, and the spells contain variations, Lepsius’ system has provided it with some sense of order and allowed later scholars to view it as a coherent piece of work.

For his work, Lepsius referred to a Book of the Dead from the Ptolemaic Period. The text was written on papyrus and belonged to a man by the name of Iufankh. Today, the artifact is housed in Turin’s Egyptian Museum.

Lepsius numbered the spells in Iufankh’s Book of the Dead from 1 to 165, and these were later divided into five segments. It may be mentioned that there were spells used during the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period that were no longer used during the Late Period, and therefore were not included in Lepsius’ work. Therefore, another Egyptologist, Edouard Naville (one of Lepsius’ students), began to assign number to these other spells, starting with the number 166.

His work was continued by Wallis Budge, who brought the number of spells to a total of 190. Since then, several new chapters have been identified and more numbers proposed. Nevertheless, scholars are cautious about adding new chapters, since it is unknown if they were considered by the ancient Egyptians as part of the Book of the Dead or another funerary text.

Although it was Lepsius who numbered the spells in the Book of the Dead, it was only much later that its internal structure was established. Although scholars have not yet fully understood the principles employed by the ancient Egyptians in the composition of individual Books of the Dead, the standardized version published by Lepsius has been divided into four main sections. This division, which attempts to decipher the logic behind the text’s sequence, was made by Paul Barguet in 1967.

Barguet divided the text into the following headings: ‘Proceeding to the burial-place’ (Chapters 1 – 16); ‘Regeneration’ (Chapters 17 – 63); ‘Transfiguration – including taking various forms; and the Judgment of the Dead’ (Chapters 64 – 129); ‘The Underworld’ (Chapters 130 – 162); and a supplementary ‘Additional formulae’ (Chapters 163 – 165).

An example of a spell from each of the four sections is as follows: ‘Formula for going out by day and living after death’ (Chapter 2); ‘Formula for opening the mouth of a man in the underworld’ (Chapter 23); ‘Formula for taking the form of Ptah, eating bread, drinking beer, excreting from the anus’ (Chapter 82); and ‘Formula for preventing the body from perishing’ (Chapter 154).

Two 'gate spells'. On the top register, Ani and his wife face the 'seven gates of the House of Osiris'. Below, they encounter 10 of the 21 'mysterious portals of the House of Osiris in the Field of Reeds'. All are guarded by unpleasant protectors. From the Book of the Dead. (The Land / Public Domain)

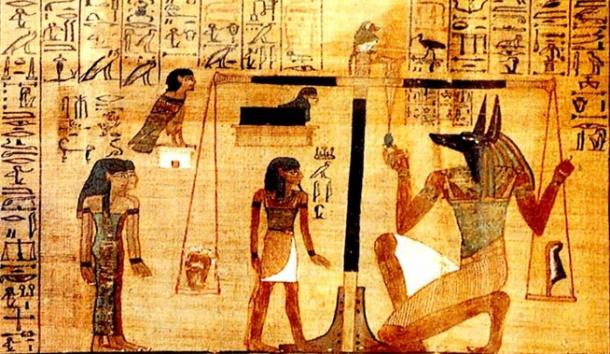

Needless to say, the ancient Egyptians believed that the journey through the underworld was a perilous one, and the deceased needed all the help they could get in order to arrive in paradise, as reflected in the spells found in the Book of the Dead. The climax of the journey, however, was the judgment of the deceased. The chief judge, of course, was Osiris, the ruler of the underworld.

In addition, there were also 42 gods who assisted Osiris in his judgment of the deceased. The spells required by the deceased for passing the final judgment in the underworld can be found in Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead.

According to Lepsius’ arrangement, Chapter 125 is known as ‘The book of entering the broad hall of the Two Goddesses Right’. This chapter is known also as the ‘Negative Confessions’, as the deceased is supposed to demonstrate his/her innocence by listing all the evil things that he/she did not do during his/her lifetime. The ‘Negative Confessions’ is fascinating not only as a funerary spell, but also as a window into ancient Egyptian morality.

The list of offences gives us some insight into what was regarded as proper and improper behavior in ancient Egypt. Chapter 125 begins with a declaration of innocence before Osiris. The deceased is then required to address each of the 42 gods accompanying Osiris.

In this spell, the names of the deities are not revealed. Instead, only their epithet and place of origin are given. Some examples of these gods are “An-hetep-f, who comest forth from Sau”, “Sekhriu, who comest forth from Uten”, and “Neheb-nefert, who comest forth from thy cavern”.

In addition to addressing the 42 gods individually, the deceased is required to declare his/her innocence once more by confessing to each of them an offence that he/she had not committed. The confessions include “I am not a man of deceit”, “I have not debauched the wife of any man”, and “I have not blasphemed”.

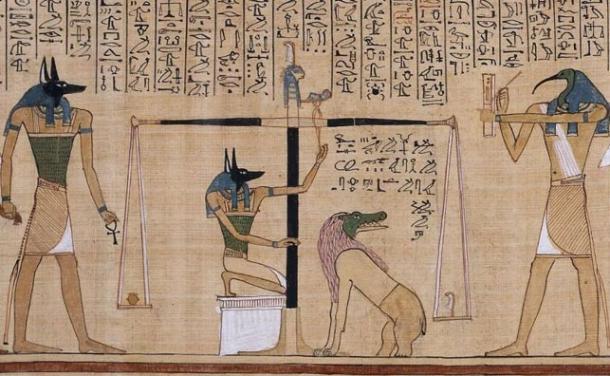

Having made his/her confessions before the gods, the final test for the deceased is the ‘weighing of the heart’, during which the heart of the deceased is weighed against the feather of Maat, the goddess of truth and justice. If the heart and the feather were of equal weight, the deceased was allowed to enter paradise. On the other hand, if the heart was heavier than the feather, it was fed to the monster Ammit, and the deceased would die a second (and permanent) death.

- Egyptian Hieroglyphs: The Language of the Gods

- Lost Artifacts of the Great Pyramid: The Mysterious Case of the Dixon Relics

- Egyptian Demons and Magic: Exorcising Evil Spirits

The ‘Weighing of the Heart’ ritual, shown in the Book of the Dead. (Alonso de Mendoza / Public Domain)

In order to prevent the heart from telling on the deceased, the ancient Egyptians had recourse. The spell in Chapter 30, is known as the ‘Formula for preventing the heart of a man being kept away from him in the underworld’. This spell was so important that it is often carved onto amulets in the shape of scarabs and placed on a mummy’s chest before it was wrapped.

A vignette in The Papyrus of Ani, from Spell 30B: ‘Spell For Not Letting Ani's Heart Create Opposition Against Him’, in the gods' domain. (FinnBjo~commonswiki / Public Domain)

Top image: Egyptian papyrus, Book of the Dead. Source: BlackMac / Adobe Stock.

By Ḏḥwty

References

Castellano, N. 2019. The Book of the Dead was Egyptians' inside guide to the underworld. [Online] Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2016/01-02/egypt-book-of-the-dead/

crystalinks.com. Date Unknown. Ancient Egyptian Funerary Texts. [Online] Available at: https://www.crystalinks.com/egyptexts.html

egyptianmyths.net. 2019. The Funerary Texts. [Online] Available at: http://www.egyptianmyths.net/funerarytexts.htm

Hill, J. 2018. Coffin Texts. [Online] Available at: https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/coffintexts/

Hill, J. 2018. Negative Confession. (Spell 125 Book of the Dead). [Online] Available at: https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/negativeconfession/

Hill, J. 2015. Pyramid Texts. [Online] Available at: https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/pyramidtext/

Moore, J. 2016. The Book of the Dead: A Practical Guide for the Recently Deceased. [Online] Available at: https://theculturetrip.com/africa/egypt/articles/the-book-of-the-dead-a-practical-guide-for-the-recently-deceased/

sacred-texts.com. Date Unknow. The Papyrus of Ani. [Online] Available at: https://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ebod/ebod12.htm

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2017. Book of the Dead. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Book-of-the-Dead-ancient-Egyptian-text

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. Coffin Texts. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Coffin-Texts

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2013. Pyramid Texts. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pyramid-Texts

The Fitzwilliam Museum. 2019. Egyptian funerary literature. [Online] Available at: https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/papyrus/bod/funeralliterature.html

Thorpe, V. 2010. Book of the Dead: Scroll down and learn how to die like an Ancient Egyptian. [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2010/oct/24/book-of-the-dead-egypt-exhibition

touregypt.net. 2019. The Negative Confessions from the Papyrus of Ani. [Online] Available at: http://www.touregypt.net/negativeconfessions.htm

University College London. 2002. Background information on the Book of the Dead - formulae for going out in the day. [Online] Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/literature/religious/bdquestions.html

University College London. 2003. The Book of the Dead, Chapters in modern numerical order. [Online] Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/literature/religious/bdbynumber.html

Warren, K. 2019. Book of the Dead: A Guidebook to the Afterlife. [Online] Available at: https://www.arce.org/resource/book-dead-guidebook-afterlife

Book of the dead

Permalink

I would love to read these spells