Pyramids of Meroë stand as Last Remnants of a Powerful Civilization

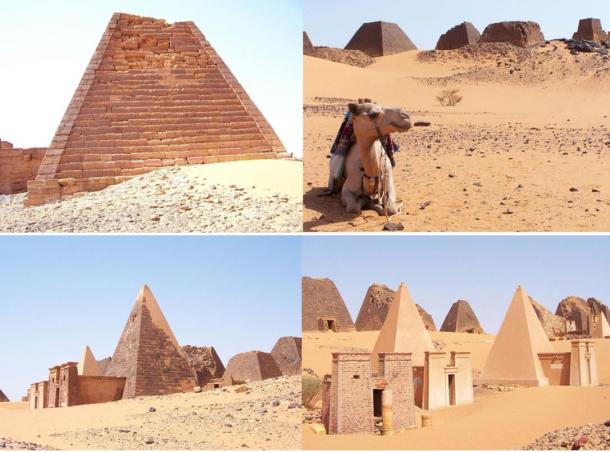

The Great Pyramids of Giza are among the most recognizable structures in the world today. Yet just south of the Egyptian border is a set of equally impressive pyramids that stand beautifully maintained in the barren landscape of Sudan. Unlike the pyramids of Egypt, however, they are deserted and rarely spoken of or visited, despite their recognition of great historical importance as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Today, the pyramids of Meroë stand as the last remnants of the great Kingdom of Kush, one of the earliest known civilizations in the Nile region.

Meroë was an important city in the ancient Kush Kingdom. According to the archaeological evidence, the city was settled as early as the beginning of the 9 th century BC. By around 300 BC, Meroë became the capital of the Kingdom of Kush, and remained so until the middle of the 4 th century AD, when it was invaded and conquered by the Kingdom of Aksum.

Photographs of the Pyramids at Meroe in Sudan, 2005. Photos taken by: Fabrizio Demartis (Wikimedia Commons)

Due to the contacts between the Kingdom of Kush and Pharaonic Egypt (the Kushites even managed to control Egypt for about a century), it was only natural for cultural practices to move between the two entities. One of the Egyptian practices adopted by the Kushites was the building of pyramids. Unlike the pyramids built by their northern neighbours, the pyramids of the Kushites were constructed using large blocks of sandstone, and have a steeper angle. Additionally, these pyramids are smaller in size when compared with the Egyptian ones. What these pyramids lack in size, however, they make up for in numbers.

At present, archaeologists have discovered more than 200 pyramids in Meroë. The pyramids are divided between three areas, the South Cemetery, the North Cemetery, and the West Cemetery. Incidentally, recent excavations at Sedeinga, a contemporary site about 700 km from Meroë, uncovered a dense field of miniature pyramids. This has been regarded as evidence that the practice of building pyramids trickled down from the royals at Meroë to provincial elites such as those living in Sedeinga.

- Could this Finding Dwarf the Pyramids of Giza? Long-Lost Pyramids Confirmed in Egypt

- The Mystery of the Miniature Pyramids of Sudan

- What is a Pyramid doing in the Heart of Rome?

An aerial view of some of the pyramids at Meroë. Photo source: Wikimedia.

Like the Egyptians, the Kushites also believed that the afterlife was a more perfect version of life on earth, and that the dead ought to be buried with the things they need in the netherworld. Unfortunately, most of the tombs at Meroë were plundered in ancient times. Some of the pyramids were further damaged in the 19 th century by the Italian explorer and treasure hunter, Giuseppe Ferlini. In his quest for the treasures of the Kushites, Ferlini is reported to have demolished the tops of more than 40 pyramids. As a result of ancient looting, however, only one pyramid was found to contain treasure, and Ferlini sold the priceless artifacts to European museums.

Despite the destruction caused over the centuries, archaeologists are still able to piece together a rough idea of the way the Kushite elites treated their dead based on the reliefs found in the tombs. According to these images, the dead were mummified, covered with jewellery, and then laid to rest in wooden coffins. In addition, later archaeological excavations have unearthed some pretty interesting artifacts. For instance, the American expedition led by George Reisner at the beginning of the 20 th century found a 5 th century BC wine vessel from Athens and a 1 st century A.D. silver wine cup from Italy, indicating that the Kushites were in contact and trading with the Mediterranean world.

- The Mysterious Ancient Etruscan Underground Pyramids Discovered in Italy

- In Search of the Legendary 1,000-ft White Pyramid of Xian

The archaeological importance of the pyramids of Meroë has earned them a place in UNESCO’s World Heritage List, as part of the ‘Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroë’. Despite this prestigious status, the pyramids of Meroë do not receive even a fraction of the tourists that visit Giza each year. According to one reporter, a ticket seller at Meroë mentioned that the site usually receives just 10 visitors a day. The fact that Meroë is much less crowded than Giza, plus the lack of merchants and ‘guides’ pestering tourists, would certainly make Meroë an attractive destination for those who wish to travel off the beaten track.

Featured image: Pyramids of Sudan. Credit: Galyna Andrushko | Dreamstime

References

Gray, M., 2014. Pyramids of Meroe. [Online]

Available at: http://sacredsites.com/africa/sudan/pyramids_of_meroe.html

Melikian, S., 2010. The Mysteries of Meroe. [Online]

Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/22/arts/22iht-melik22.html?_r=1

Powell, E. A., 2013. Miniature Pyramids of Sudan. [Online]

Available at: http://www.archaeology.org/issues/95-1307/features/940-sedeinga-necropolis-sudan-meroe-nubia

Smith, D., 2014. Sudan: pyramids, souqs and Gaddafi's hotel in the land tourism forgot. [Online]

Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/09/-sp-sudans-tourist-gems-pyramids-gaddafi-bin-laden

UNESCO, 2015. Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe. [Online]

Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1336

Zijlma, A., 2015. The Meroe Pyramids, Sudan. [Online]

Available at: http://goafrica.about.com/od/peopleandculture/p/meroepyramids.htm

By Ḏḥwty

Comments

I'd think all the unrest in the Sudan would be the reason why so few people visit this site.