Khentkawes I: The Mysterious Mother of two Kings of Egypt and a Forgotten Ruler of the 4th Dynasty

Queens of Ancient Egypt played significant roles throughout history both in life and in death, but the attention is usually given to striking noble women such as: Nefertiti, Hatshepsut, Nefertari, Cleopatra, and a few others. The stories told of these prominent royal women are enough to fill libraries and a plethora of artifacts pertaining to them are carefully preserved in museums. However, lesser-known queens— particularly Khentkawes (Khentkaus) I—are just as deserving of consideration for their lives and accomplishments as rulers.

The Rediscovery of Khentkawes I Tomb

Renowned as the mother of two Egyptian pharaohs, Khentkawes I is a mysterious figure who ruled in the 4th dynasty and has intrigued historians and archaeologists since the discovery of her burial complex at Giza. Though evidence for ancient Egyptian queens is as fragmented as their male counterparts at times, the remains of this female leader were undisturbed for two millennia within the necropolis until its excavation in the 1930s.

Her mastaba is believed to have been the final royal tomb that was constructed at the necropolis, and many scholars believe that it is strongly connected to Pharaohs of the 4th and 5th Dynasties. Evidence shows us that Khentkawes I unquestionably left her imprint in Egypt.

An orthophotographic point cloud (3D survey) image of Khentkawes I’s Tomb in Giza, Egypt. (Yukinori Kawae/Ancient Egypt Research Associates)

Title as the Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt

The status of Khentkawes I status in ancient Egypt has been argued since the location of her pyramid complex became known in the twentieth century. She was born circa 2550-2520 BC and died sometime between 2510-2490 BC. Many scholars believe her to be the daughter of Menkaure and the wife of king Shepseskaf (who reigned between 2510-2502 BC). It is said that Khentkawes I bore two children who went on to become successful pharaohs.

- New Study Presents Evidence of Extensive Inbreeding among Ancient Egyptian Royalty

- Ten Powerful and Fearsome Women of the Ancient World

- Archaeologists uncover 4,200-year-old Tombs of ancient Egyptian priests

Archaeologist Selim Hassan first implied the queen’s significance as a ruler following the examination of her burial complex in 1933. Hieroglyphic inscriptions concerning her title had been discovered and subsequently became open for interpretation. Her title was initially regarded to be ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt’ and then a “philologically tenable” substitute that translated her title to “mother of two kings” was proposed by British Egyptologist Alan Gardiner. However, due to later archaeological discoveries, Khentkawes I’s formal title is construed to be Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, [holding office as] King of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Khentkawes I’s Grand Burial Structure

Khentkawes I’s burial structure, known as LG100 and G8400, is located in the Giza Central Field. Cut from the rock of a nearby quarry, many features of the tomb were partially damaged during the antiquity era but there are several remaining aspects that allow one to reconstruct some of the phases of the royal woman’s life.

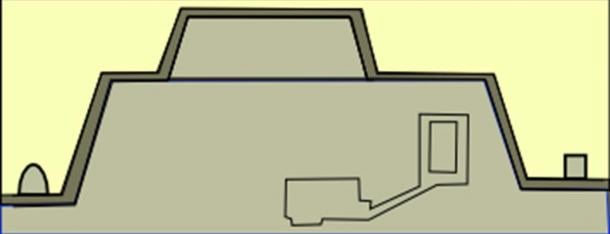

Unfortunately, the public are not able to view the structure from the inside but its stratigraphy is highly noticeable from the outside. From the outside, it is visible that the structure resembles a step-pyramid, with two steps and a passage, as well as a superstructure built on top. There are also cased outer walls reminiscent of other complexes built at the time, particularly comparable to King Shepseskaf’s funerary monument in Saqqara.

Cross-section of Khentkawes I tomb, Giza, Egypt. (CC By SA 2.5)

The mausoleum is as grand as other pyramids of her predecessors and includes a solar boat, a chapel, granaries and a water tank. Inside, there is a sloping passage that descends into the underground chambers and an antechamber to deter grave thieves was intricately built. Adjustments and additions were made until the 6th dynasty—possibly a reflection of her continued role in folklore and religion after her death.

A boat pit, for instance, is a common feature of royal mausoleums from as early as the Early Dynastic era. The exact functions of these boat pits are unknown, but they have been considered to be related to religious practices. Boats may have acted as the vessels to facilitate one’s transition to the afterlife and many deem them to be a representation of the sun god Ra.

Interestingly, Khentkawes I was depicted on a granite column grasping onto a scepter and wearing the royal ‘uraeus’ cobra at her brow and a false beard of kingship combined with her traditional female garments, (although her name is not written on the cartouche,) this is another strong indication of her being a ruler.

Khentkawes I as depicted in her tomb. Giza, Egypt (Jon Bodsworth/Wikimedia Commons)

The Settlement Located Near Khentkawes Tomb

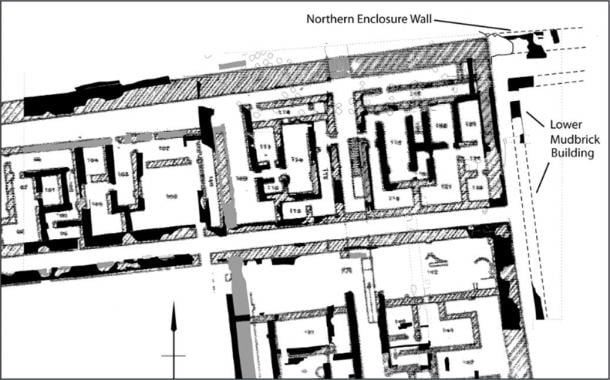

In addition, there is a small settlement made of mudbrick with many streets that is located on the east side of Khentkawes I’s burial structure. Granaries and a magazine were discovered in this settlement. Experts believe that this area may have been a residential space for religious rituals or for employees involved in religious practices around Giza.

The settlement to the east of Khentkawes I’s burial structure. (Lisa Yeoman/Selim Hassan)

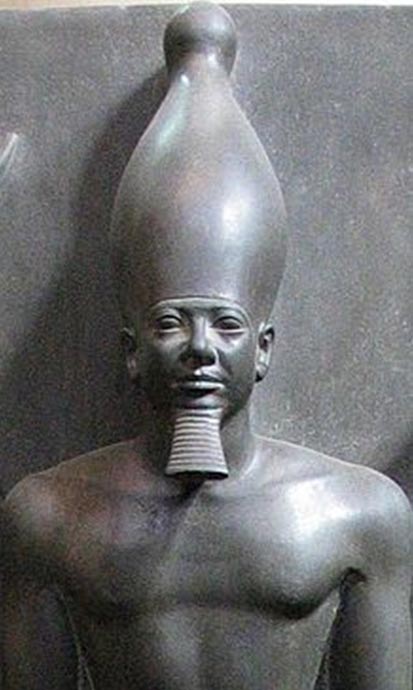

There is a path that joins the pyramid chapel to the valley temple of Khentkawes I, which is also found near to the temple of Menkaure. Due to the close proximity of the two, many people believe that the royals had a very close relationship. A small structure known as the “washing tent of the female king” had been built in front of her temple and here the body of the lifeless Khentkawes I was washed and ritually purified prior to being embalmed.

Statue of Menkaure, Egyptian Museum, Cairo. The temples of Menkaure and Khentkawes I are close together leading many to believe that there was some kind of familial relationship between the two. (CC by SA 3.0)

Further Indications of Khentkawes I High Status and the Discovery of Khentkawes II

According to Ana Tavares, a field director of on-going excavations occurring at the Giza site, the “valley temple and basin/harbor” is an indication of Khentkawes I’s kingly position as pharaoh—such manifestations were usually reserved for people of the highest status.

- Hatshepsut: The Queen who became King

- Reconstructed Temple of the Night Sun in Mortuary of Queen Hatshepsut opens to the public

- Archaeologists unearth tomb of previously unknown Queen in Egypt

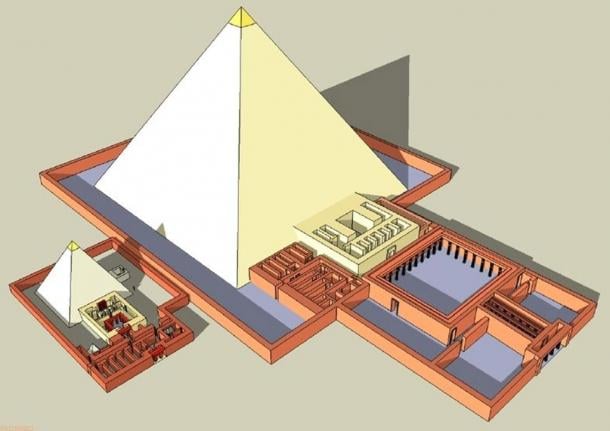

The mysterious quality of Khentkawes I's role in Egypt intensified when Czech archaeologists working within Abusir discovered a pyramid belonging to a Queen Khentkawes in the 1970s. Initially believed to have been the same She King, as she was given the same title and portrayed adorning similar royal attire, it was later discovered that the true owner was the wife of Neferirkare and mother of Neferefre, - the two women were in reality a generation apart. Confusion continues, but the royal woman found at Abusir has now been identified as Khentkawes II.

The pyramid complex of Khentkaus II (smaller) and her husband Neferirkare Kakai from Abusir, Egypt. (Wikimedia Commons)

Although research regarding mysterious royal women such as Khentkawes I is lacking in comparison to better-known queens of Egypt, a reconstruction of her life is slowly beginning to appear. One day, the story of Khentkawes I and her true roles will come to full light.

Featured image: The mastaba of Khentkawes I, Giza, Egypt. (Jon Codsworth/Wikimedia Commons).

References

Shaw, Ian. Nicholson, P. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. New York: Abrams Inc. 1995.

Simpson, W.K. The Mastabas of Kawab, Khafkhufu I and II. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. 1978.

Smith, W.S. Inscriptional Evidence for the History of the Fourth Dynasty. JNES XI (1952).

Verner, M. The Pyramids. New York: First Grove Press, 2001.

Hassan, Selim. Excavations at Giza IV. 1932–1933. Cairo: Government Press, Bulâq, 1930.