Palmyra Busts - A Window into the Ancient Palmyra’s Customs

Throughout history, many ethnicities and civilizations were often distinguished by their funerary beliefs and burial customs. From the Egyptian pyramids to the Neolithic Passage tombs, burial always had a special meaning for ancient peoples. The inhabitants of ancient Palmyra, a wealthy trade city whose ruins are situated in modern-day Syria, also had their one-of-a-kind burial custom. Their exquisitely carved Palmyra busts were a unique way of portraying the deceased and preserving their likeness throughout the centuries. Thanks to the skill with which they were carved, we can today learn a lot about this ancient culture, and see the faces of people who lived thousands of years ago.

The Palmyra Busts Serve as a Window into the Past

The ancient city of Palmyra, also known as Tadmor in Arabic, was a significant cultural and commercial hub located in present-day Syria. It is renowned for its well-preserved ruins, which showcase a unique blend of Roman and Persian architectural styles. Palmyra's history dates back to the second millennium BC, with evidence of habitation from the Neolithic period. However, it rose to prominence during the first and second centuries AD when it became a vital trading center along the Silk Road, connecting the Roman Empire in the west with Persia, India, and China in the east. Palmyra's strategic location at the crossroads of several trade routes contributed to its prosperity.

The city was originally inhabited by Semitic peoples, likely belonging to the Aramaeans. Over time, Palmyra's culture and society became a fusion of Roman, Greek, and Persian influences. The city was known for its distinct art, religious practices, and unique architecture, which reflected this multicultural synthesis. One of the most famous figures associated with Palmyra's history is Queen Zenobia (Septimia Zenobia). She was a capable and ambitious ruler who, after the death of her husband, King Odaenathus, took control of the city and expanded its territory. At its height, the Palmyrene Empire encompassed parts of modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt. However, her conflict with the Roman Empire eventually led to her defeat and the reassertion of Roman control over the region.

Syria. Palmyra (Tadmor). The central part of the Great Colonnade leading along Main Street. This site is on UNESCO World Heritage List. (WitR/AdobeStock)

Thanks to its wealth and success, Palmyra was able to focus on its unique culture. The architectural wonders of Palmyra included grand colonnades, temples, theaters, and tombs. The Great Colonnade, a 1.2-kilometer-long (0.75 mi) street lined with columns, was a particularly impressive feature of the city. It served as a processional way and commercial center, showcasing Palmyra's prosperity and grandeur. And equally magnificent were the famed Palmyra Busts, which were built in their thousands, and many survived unscathed to the present day.

- Gone Forever? The History and Possible Future of the Recently Destroyed Monumental Arch of Palmyra

- Scholar Made the Ultimate Sacrifice to Save Ancient Palmyra Treasures from the Hands of ISIS

A Unique Funerary Custom Exclusive to Palmyra

The Palmyra Busts are also known as the Palmyrene statues or Palmyrene funerary busts. They are remarkable examples of the artistic and cultural heritage of the ancient city. Artistically, they blend a traditional Palmyrean element with distinct Roman influences. They are a clear insight into the cultural exchange between these two civilizations, and how powerful the influence of Roman art was. Most of the busts date to the middle of the first century BC, when Palmyra was at the height of its power and wealth. The busts were placed atop the burial monuments of the deceased and served as a way to honor and remember them in death.

The busts were sculpted from limestone, a common material in the region, which allowed for intricate details and skilled craftsmanship. Limestone is easy to work with and to shape, and it is lasting to boot. The statues were usually carved in a semi-realistic style, capturing the facial features and clothing of the deceased individuals, in great detail. The sculptors demonstrated their skill in representing the individualized traits of the people they depicted. However, scholars today think that the likenesses were rather symbolical, and not the exact representations of the deceased.

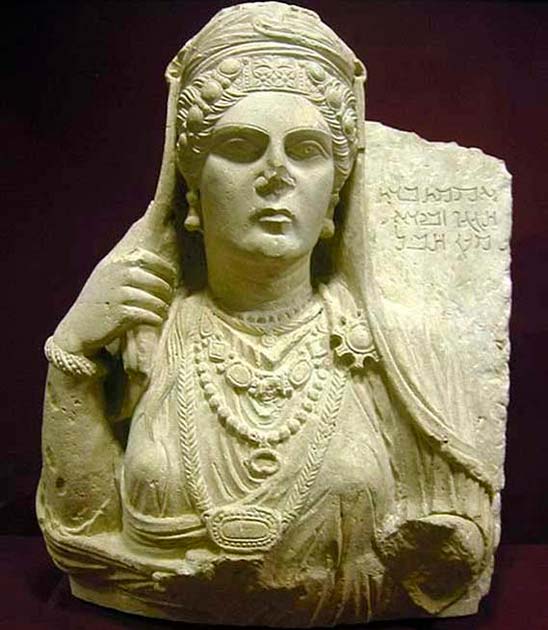

Funerary bust of Aqmat, daughter of Hagagu, descendant of Zebida, descendant of Ma'an, with Palmyrenian inscription. Stone, late 2nd century AD. From Palmyra, Syria. (CC BY SA 3.0)

One of the fascinating aspects of the Palmyra Busts is the fusion of different cultural influences in their artistic style. The busts showcase a blend of Greco-Roman artistic traditions with distinct local elements, reflecting the multicultural nature of Palmyra. The artists often portrayed their subjects wearing Roman-style clothing and hairstyles but incorporated local and Persian influences in the portrayal of facial features. Many of the Palmyra Busts feature inscriptions in the Palmyrene Aramaic script, providing valuable information about the deceased individuals and sometimes their families. These inscriptions often contain the names of the deceased, their titles or professions, their family connections, and occasionally, religious or mythological references. This served as a great way for historians to study the Palmyrene script and language.

- Erasing History: Why Islamic State is Blowing Up Ancient Artifacts

- Valuable 3,500-Year-Old Statue of a Syrian Refugee Turned King from Aleppo Goes Online

With the End of Palmyra Came the End of the Busts

The Palmyra Busts were rediscovered during archaeological excavations in the 20th century. Many of these sculptures were found in funerary contexts, often adorning tombs and burial chambers. Some of the busts were displayed in the National Museum of Damascus, showcasing their significance as cultural artifacts. At the time of their discovery, they were amongst the most precious finds from Palmyra: the level of detail helped recreate the clothing, jewelry, and other cultural aspects of ancient Palmyra.

Alas, the Roman Empire put an end to this tradition - and to Palmyra altogether. After the Crisis of the Third Empire, Palmyra made an attempt to create a vast Empire in the region, led by Queen Zenobia. But one does not challenge the Roman Empire so easily. Zenobia’s attempt was quickly met with Rome’s wrath. Palmyra was destroyed and subsequently abandoned - forever. It was a brutal and quick end to a centuries-old city.

Top image: Limestone bust from a Palmyrene funerary relief; double bust of man and his wife; she is veiled with the fillet; wears drop ear-rings and two long curls of hair; holds in left hand distaff and spindle; he wears a toga and holds a strip of writing material in his right hand; inscription; 2 ll. Inscription: OYIPIA ( ) OIBH () AIOCOYIIOC () KIMOC - Viria Phoebe and Gaius Vurus. Left: Bust of a noblewoman nicknamed "Beauty of Palmyra” Copenhagen, Denmark. Source: Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany/CC BY-SA, FunkMonk/CC BY-SA 4.0

References

Colledge, M. A. R. 1976. The Art of Palmyra. Westview Press.

Heyn, M. K. 2010. Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra. American Journal of Archaeology.Ingholdt, H. 1954. Palmyrene and Gandharan Sculpture: An Exhibition Illustrating the Culture Interrelations Between the Parthian Empire and its Neighbors West and East. Yale University Press.