Eretria is an ancient Greek city state located in the southern part of Euboea, a Greek island facing the coast of Attica. Eretria is said to have been founded during the 8th century BC and was one of the Greek city states that played an important role in the Greek colonization movement, which lasted from the 8th to the 6th centuries BC.

At the beginning of the 5th century BC, Eretria was destroyed and its population deported by the Achaemenid ruler, Darius I the Great, as punishment for their involvement in the Ionian Revolt. Although the Persians did not succeed in turning Greece into one of their satrapies, Eretria fell under the dominion of Athens after the Graeco-Persian Wars.

During the 4th century BC, Eretria became a part of the Macedonian Empire, before falling to the Roman Republic during the 2nd century BC. Eretria was destroyed during the First Mithridatic War and gradually fell into decline after that. The city was eventually abandoned and the present town was only recently founded during the 19th century.

The History of Eretria

The name ‘Eretria’ means ‘City of the Rowers’ and is an indication of the city’s strong links to the sea. The site was already occupied by humans as early as prehistoric times. This is evident in the finding of pottery sherds from the end of the Neolithic period at the site. The sherds also suggest that during that period, the people inhabiting the site were in contact with other Neolithic communities in the Aegean, and further up in the north.

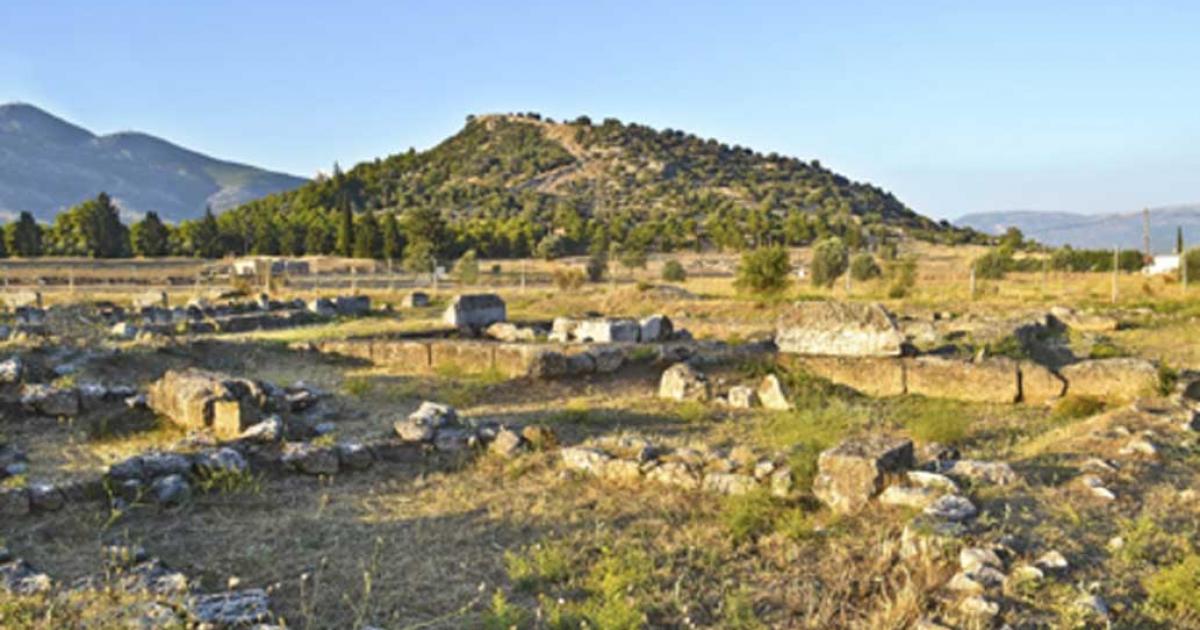

Eretria known as ‘City of the Rowers’. (Dan Diffendale / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Eretria continued to be inhabited during the Early and Middle Helladic periods. The Helladic period refers to the Early Bronze Age in mainland Greece, which lasted from about 3200 to 2100 BC. Among the buildings from this period that have been discovered at Eretria are the remains of a pottery kiln, which indicates that the people of the town were participating in industrial activities.

The last phase of the Greek Bronze Age is known as the Mycenaean period, which lasted from around 1600 to 1100 BC. The finds at Eretria that date to this period, though not many, show that Eretria was prosperous, and its people enjoyed a high standard of living. Eretria was a significant enough settlement, as it was mentioned in the Catalogue of Ships, in Book II of Homer’s Iliad, though not a major settlement like Mycenae, Tiryns, or Pylos.

After the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization, Greece entered the so-called ‘Dark Ages’ (less controversially known as the Early Iron Age). One of the best-known sites from this period is Lefkandi, situated on the island of Euboea, and not far to the west of Eretria.

The archaeological evidence shows that during the ‘Dark Ages’, Lefkandi was a large but scattered settlement, with a loose cluster of houses and villages spread over a large area. It is also estimated that the population of Lefkandi at that time was fairly low.

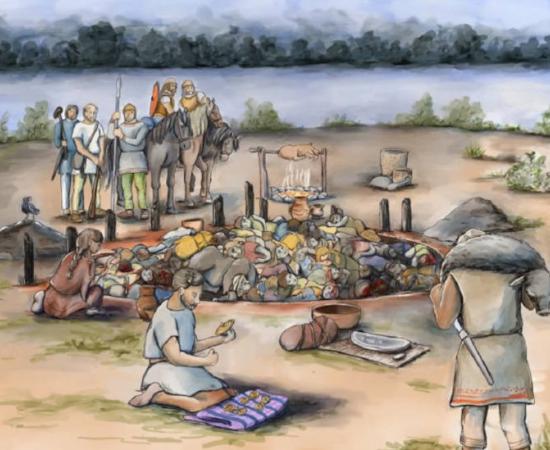

One of the most intriguing finds at Lefkandi is a cemetery called Toumba, named as such due to its location on the lower east slope of the Toumba hillock. Within this cemetery are the remains of a structure thought to be a heröon (a hero shrine). The size of the heröon at Lefkandi is impressive, being 10 times as large as any known contemporary structure in the area.

- Archaeologists Explore Incredible Ancient City in Supposed Backwater Region of Greece

- Satraps of the Persian Empire – Rebellious Protectors of the Realm

- Eagle Mistakes Bald Head for a Rock: The Bizarre Circumstances Surrounding the Death of Aeschylus

Heroon of Lefkandi, as seen from the main door. Lefkandi is a coastal village on the island of Euboea close to Eretria. (Pompilos / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Beneath the heröon, a number of rich burials have been found. Grave goods include an amphora from Cyprus, a Babylonian gorget, an electrum ring, and faience scarabs, all of which indicate that the inhabitants of Lefkandi were trading with civilizations outside Greece. The heröon and its graves therefore challenge the notion that the ‘Dark Ages’ were a time Greek civilization was in decline.

Lefkandi’s connections with the outside world meant that a port was required so that trade ships from other civilizations could dock. Some have suggested that Eretria may have originally been founded as a port for Lefkandi. One of the factors contributing to the site’s suitability as a port is the presence of a tall mountain, Mount Olympus, to the northeast of Eretria.

This would have been a prominent landmark and would have made it easy for ships to find the port. Some ancient authors, the geographer Strabo, for instance, wrote that Eretria was actually a colony of Athens.

A third foundation story, or more precisely, foundation myth, states that the city was founded by Apollo Daphnephoros, ‘Apollo bearing the laurel’, who is worshiped as the patron god of the city. In any case, as time went by, Lefkandi gradually went into decline, and was ultimately abandoned, while Eretria continued to flourish.

Landscape of the ancient city of Eretria (photo_stella / Adobe Stock)

Eretria Becomes a Prominent City

It was during the 9th century BC that Eretria became a prominent city state as a result of its participation in the Greek colonization movement, which occurred between the 8th and 6th centuries BC. During this period, the Greek city states sent settlers to establish colonies in other parts of the Mediterranean, including Sicily and southern Italy (which became known as Magna Graecia, meaning ‘Great Greece’), the coast of North Africa, and as far west as the Mediterranean coasts of modern France and Spain.

Greek colonies were also founded along the coast of the Black Sea, including Thrace, the Crimea, and the northern coast of Anatolia. Eretria is recorded to have founded such colonies as Pantikapaion and Phanagoreia in the Crimea, as well as Pithikouses and Cumae (co-founded with its neighbor, Chalcis) in Italy.

Eretria had commercial ties not only with its colonies, but also with other civilizations in the eastern Mediterranean. This is evident in the discovery of Eretrian pottery in places like Asia Minor, Syria, Lebanon, and Cyprus. No doubt, Eretria grew rich and influential as a result of trade.

Two-headed phial, one of the notable pieces of pottery from ancient Eretria. (Jona Lendering / Public Domain)

The city’s prosperity, however, was viewed as a threat by its neighbor and rival, Chalcis. As a consequence, a war broke out between the two Euboean city states. This war is known today as the Lelantine War, and its name is derived from the Lelantine Plain that separates Eretria and Chalcis. It was here that one of the battles took place, during which the Chalcidians, thanks to the Thessalian cavalry, defeated the Eretrians.

The significance of this conflict is seen in the fact that it was not just a war between two individual cities, but one that involved two coalitions. The allies of Chalcis included Samos, Corinth, and Thessaly, while Eretria was supported by Miletus, Megara, and perhaps Chios as well.

Eretria Loses Some of Its Influence

The Lelantine War broke out during the late 8th century BC, though its exact dates are unclear. Neither was there a clear victor at the end of the war. For instance, while Eretria lost its influence in the west (both sides of the Straits of Messina were controlled by Chalcis, as were the richest agricultural sites in Sicily), it retained its influence in Euboea, and may have even grown stronger after the war.

Moreover, Eretria still had the resources required to establish colonies. Among the colonies founded by the Eretrians during this period were Therma (which would later be known as Thessaloniki), and cities on the Pallene and Athos peninsulas.

In spite of that, the Lelantine War had taken its toll both on Eretria and Chalcis. As a consequence, Euboea, which had been one of the most advanced regions in Greece, slowly declined into a backwater.

Around the end of the 6th century BC, Eretria became a democratic city state. Around a century later, in 499 BC, the Ionian Revolt broke out. The revolt was initially led by Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus, and therefore originated in that city state.

The Ionian Revolt however, soon spread to other parts of Asia Minor as well. This revolt saw the Ionians rebelling against their Persian overlords. Aware that the Ionians were not powerful enough to take on the Persians by themselves, Aristagoras sought help from the city states of mainland Greece.

While the Spartans refused to send help, Aristagoras secured 20 ships from Athens. Eretria also sent five ships to Asia Minor. The Milesians had sided with Eretria during the Lelantine War, so the small fleet of five ships was meant to repay this debt.

Lelantine War. (Wikibelgiaan / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Following the retreat by the Ionian forces from Sardis in 498 BC, a battle took place between the Persians and the rebels not far from Ephesus, during which the latter was soundly beaten. The Eretrian commander was killed during the battle, and it is assumed that the remaining Eretrian troops returned home. The Ionian Revolt ended in 493 BC, following the brutal reconquest of the rebel provinces by the Persians.

Eretria is Targeted by the Persians

In the following year, the Persian ruler, Darius I the Great, launched the first Persian invasion of Greece, as he had vowed to punish Athens and Eretria for the aid they had given to the Ionian rebels. The Persians arrived in Eretria in 490 BC, razed the city to the ground, and had its inhabitants deported to Elam. As late as the middle of the 1st century AD, the descendants of these exiled Eretrians could still be recognized.

During the sacking of Eretria, many of its citizens were hiding in Oropus, a town on the opposite shore, and therefore successfully evaded capture by the Persians. During the second Persian invasion of Greece, which was launched by Darius’ successor, Xerxes I the Great, the Eretrians participated in the Battle of Artemisium (480 BC), the Battle of Salamis (480 BC), and the Battle of Plataea (479 BC). Although the first of these three battles was won by the Persians, they were defeated during the other two battles, and therefore failed to conquer Greece.

Battle of Salamis. (Alonso de Mendoza / Public Domain)

Although the Greeks had successfully defended their homeland, it was unknown at that time whether the Persians would try to conquer Greece once again. Therefore, the Delian League, a confederacy of Greek states with its headquarters on the island of Delos (hence its name), was founded in 478 BC, in order to defend Greece in the event of another Persian invasion. Apart from that, the founding of the Delian League was also aimed at supporting the Greeks in Asia Minor against the Persians.

The Spartans, however, were reluctant to support this overseas war, and thus did not join the league. Without the Spartans, the Athenians did not have any competition, and therefore became the leaders of the Delian League. Eretria, as well as the rest of Euboea, was a member of the league.

Tensions between Athens and Sparta rose in the decades that followed, though the Thirty Years’ Treaty was signed in 445 BC. Hostilities were renewed in 433 BC, and two years later, the Peloponnesian War broke out between the Delian League and Peloponnesian League, i.e. Sparta and its allies. During this war, the Athenians were not only fighting against the Peloponnesian League, but also had to deal with rebellions by the league’s members.

This was due to the fact that Athens had turned the Delian League into an Athenian Empire, and its less powerful members were not satisfied with it. This included the Eretrians, who tried to leave the league in 446 BC, though they were not successful in doing so.

In 411, Eretria, along with other Euboean cities, successfully revolted against Athens. Eretria prospered in the decades that followed, and renovations were carried out on the city walls and the Agora. Nevertheless, the city was later recaptured by the Athenians and became part of the Second Delian League.

In 338 BC, the Battle of Chaeronea was fought between a new power in the region, Macedon, and a coalition of Greek city states led by Athens and Thebes. The Greeks were crushed during the battle, and Macedon now exerted its influence over much of Greece, including Eretria. Under the Macedonians, Eretria enjoyed a period of prosperity, which enabled them to construct such monuments as the Theatre, the Temple of Dionysus, the northern Gymnasium, and the southern Palaestra.

The ancient Theatre of Eretria. (Bdubosso / CC BY-SA 3.0)

- King Leonidas of Sparta and the Legendary Battle of the 300 at Thermopylae

- Archaeologists discover Mycenaean palace and treasure trove of artifacts in southern Greece

- Apadana – The Everlasting Hall of the Achaemenids

Aerial view of the Apollo Daphnephoros Temple at Eretria. (Tomisti / CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 200 BC, the Second Macedonian War broke out between the Macedonians and the Romans. In 198 BC, the Romans besieged, captured, and sacked Eretria. It has been speculated that the famous painting of the Battle of Issus, made by Philoxenus of Eretria for Cassander, was one of the spoils of war seized by the Romans. The painting was copied in Rome and is preserved in the form of the Alexander Mosaic in Pompeii.

The Romans allowed Eretria to maintain its independence. During the First Mithridatic War, which broke out in 89 BC, the Eretrians sided with Mithridates, the king of Pontus, against Rome. As punishment, the Romans destroyed Eretria in 86 BC.

From then on, Eretria gradually declined, until it was abandoned during the 6th century BC. Eretria was re-founded in 1834, when the town of Nea Psara was established. Since 1964, archaeological work has been carried out at the site by the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece.

Top image: Landscape of the ancient city of Eretria, Euboea, Greece. Source: photo_stella / Adobe Stock

By Wu Mingren

References

Anastopulos, H. 2019. Lefkandi. [Online] Available at: https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/greekpast…

Blakely, S. 2006. Myth, Ritual and Metallurgy in Ancient Greece and Recent Africa. Cambridge University Press.

Current World Archaeology. 2010. Lefkandi. [Online] Available at: https://www.world-archaeology.com/features/lefkandi/

Hemingway, C., and Hemingway, S. 2003. Mycenaean Civilization. [Online] Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/myce/hd_myce.htm

Hirst, K. 2019. Lefkandi (Greece). [Online] Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/lefkandi-greece-village-cemeteries-171525

Lendering, J. 2019. Eretria. [Online] Available at: https://www.livius.org/articles/place/eretria/

Ministry of Culture and Sports. 2012. Eretria. [Online] Available at: http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/3/eh351.jsp?obj_id=5988

Museum of Cycladic Art. 2019. Greek Colonisation. [Online] Available at: https://cycladic.gr/en/page/ellinikos-apikismos

Rickard, J. 2015. Ionian Revolt, 499-493 BC. [Online] Available at: http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/wars_ionian_revolt.html

Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece. 2019. Eretria. [Online] Available at: https://www.esag.swiss/eretria/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2015. Delian League. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Delian-League

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2013. Eretria. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Eretria

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Euboea. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Euboea-island-Greece

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2017. Lelantine War. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Lelantine-War

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Peloponnesian War. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Peloponnesian-War

www.fhw.gr. 2019. Early Bronze Age on the Greek Mainland. [Online] Available at: http://www.fhw.gr/chronos/02/mainland/en/eh/intro/index.html