Cultures evolve or change over the ages; this is an undeniable fact. However, many of the practices of ancient people and cultures would be practically incomprehensible for most people today. Be they dangerous, painful, or just plain odd by today’s standards, the following are some examples of traditions that would not thrive in the modern world.

Foot Binding

The ancient origins of foot binding are not known for certain, but according to some accounts, it goes back as far as the Shang dynasty (1700 – 1027 BC). Legend says that the Shang Empress had a clubfoot, so she demanded that foot binding be made compulsory in the court. However, historical records from the Song dynasty (960 - 1279 AD) date foot binding as beginning during the reign of Li Yu, who ruled over one region of China between 961 and 975 AD. By the 12th century, foot binding had become much more widespread, and by the early Qing Dynasty (in the mid-17th century), every girl who wished to marry had her feet bound.

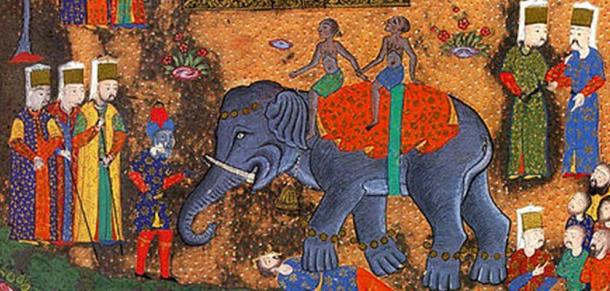

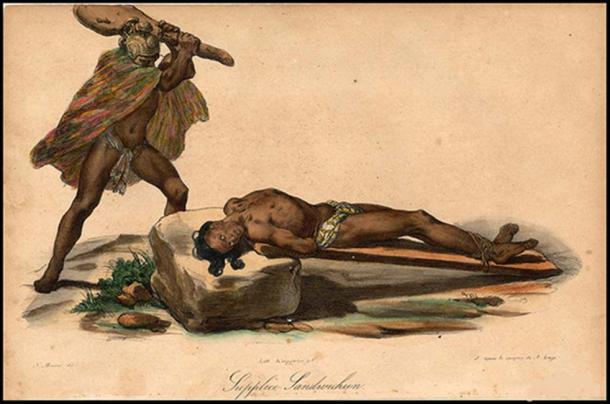

Execution by Elephant

Execution by elephant was a form of capital punishment and a weapon of war for certain societies of the past. This method of punishment was occasionally used in the Western world and several examples can be found in ancient sources. It was more frequently used in South and Southeast Asia, especially in India. This form of capital punishment is known also as gunga rao, and has been used since the Middle Ages. The popularity of this mode of execution continued into the 19th century, and it was only with the increasing presence of the British in India that the popularity of this brutal penalty went into decline.

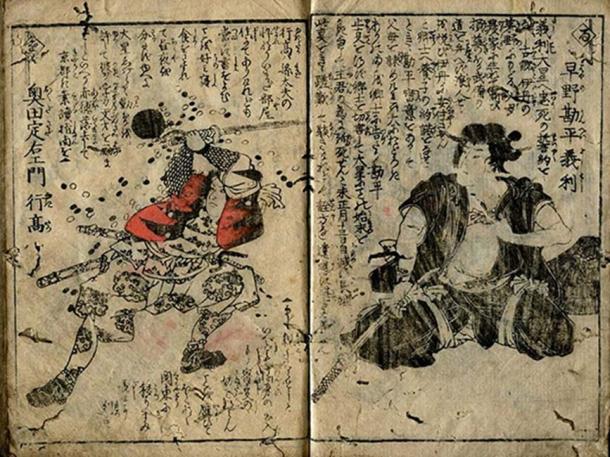

Seppuku

While martial suicide is a practice found in a lot of cultures, the act of seppuku, or ritual self-disembowelment, is peculiar to Japan. The earliest known acts of seppuku were the deaths of samurai Minamoto Tametomo and poet Minamoto Yorimasa in the latter part of the 12th century.

In a typical seppuku, a large white cushion would be placed and witnesses would arrange themselves discreetly to one side. The samurai, wearing a white kimono, would kneel on the pillow in a formal style. Behind and to the left of the samurai knelt his kaishakunin (his “second” or assistant), ready to prevent the samurai from experiencing prolonged suffering by cutting the samurai’s head off once he had slit his stomach.

High Heels for Men

High heels were, at various points of time in history, worn by men as well as women. Whilst it is unclear when high heels were first invented, they were used by ancient Greek actors. The ‘kothorni’ was a form of footwear worn from at least 200 BC, which raised from the ground by wooden cork soles. It is said that the height of the shoes served to differentiate the social class and importance of the various characters that were being portrayed on the stage.

The next appearance of high heels can be traced to the Middle Ages in Europe. During this period, both men and women wore a kind of footwear known as pattens. The streets of many Medieval European cities were muddy and filthy, whilst the footwear of that period were made of fragile and expensive material. Thus, to avoid ruining these garments, both men and women wore pattens, which were overshoes that elevated the foot above the ground and out of the muck.

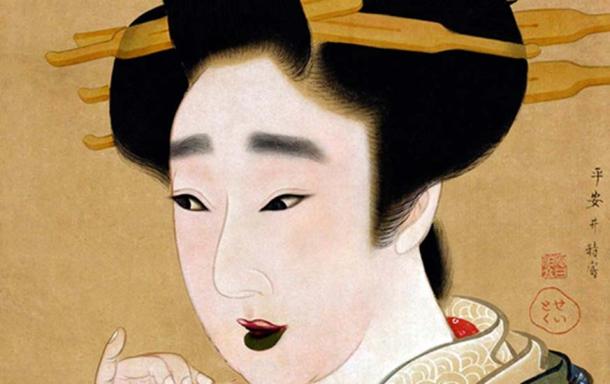

Blackened Teeth

Ohaguro (which may be translated as ‘blackened teeth’) is a practice in which people (usually women) dye their teeth black. Whilst this custom is known to be practiced in different parts of the world, including Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and even South America, it is most commonly associated with Japan. Until the end of the 19th century, black teeth were regarded as a sign of beauty in Japan. But they were more than just a mark of beauty in Japanese society, and served other purposes as well – such as symbolizing a woman’s sexual maturity.

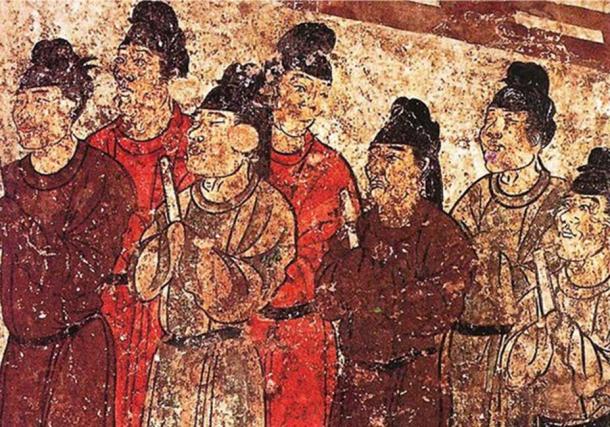

Human Sacrifice

Human sacrifice was practiced in many early human societies throughout the world. In China and Egypt the tombs of rulers were accompanied by pits containing hundreds of human bodies, whose spirits were believed to provide assistance in the afterlife.

Ritually slaughtered bodies are found buried next to rings of crucibles, brass cauldrons and wooden idols in the peat bogs of Europe and the British Isles. Early explorers and missionaries documented the importance of human sacrifice in Austronesian cultures, and occasionally became human sacrifices themselves. In Central America, the ancient Mayans and Aztecs extracted the beating hearts of victims on elevated temple altars. It is no surprise, then, that many of the oldest religious texts, including the Quran, Bible, Torah and Vedas, make reference to human sacrifice as well.

Make-Up Full of Crocodile Dung

Unlike the Greeks and Egyptians, the Romans used makeup to preserve the natural beauty of a woman and not to embellish the facial canvas into a cacophony of colors. The ideal Roman female was a woman of extraordinary white skin as it was evidence to onlookers that she spent much of her time indoors, thus was wealthy enough to afford servants and laymen. However, since the natural skin tone of a Roman woman was closer to olive than ivory, there was still a necessary unnatural process of powdering the face. This involved the use of chalk powder, crocodile dung, and white lead to whiten their entire face.

Eunuchs

In ancient China (up until the Sui Dynasty), castration was one of the Five Punishments, a series of physical punishments meted out by the Chinese penal system. It was also a means of getting a job in the Imperial service. Since the Han Dynasty, eunuchs ran the day to day affairs of the Imperial court. There, eunuchs had the potential to amass an immense amount of political power. Since they were unable to have children of their own and pass down their power, eunuchs were not seriously considered a threat to the ruling dynasty. The powerful emperors of China would sometimes have thousands of concubines within the Forbidden City, with no risk that the women would become impregnated by anyone but themselves.

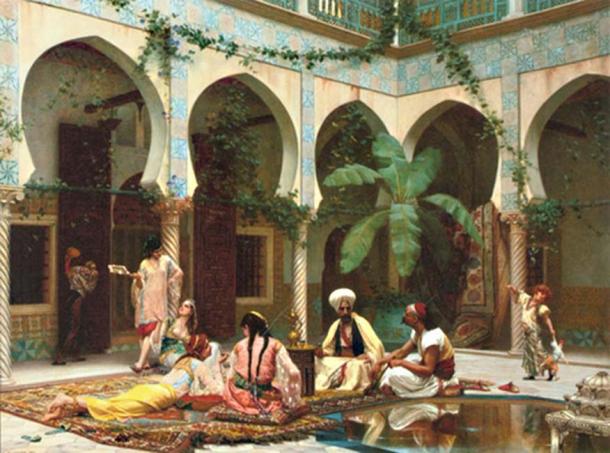

Harems

The term harem comes from the Arabic haram meaning forbidden place. This defines the sphere of women in a polygynous household and makes reference to their enclosed quarters being forbidden to men. The word first appeared in the Middle East, where harems were composed of sultans, mother, sister, wives, children, and concubines. The South Asian equivalent of the harem is the zenana.

As the harem had a secluded nature, there are no exact sources which can present the truth of harem life. Instead, there are only imaginative representations available about what happened within the harem. However, it is known that during the Ottoman Empire the role of the harem was that of the royal upbringing of the future wives of noble and royal men. These women were specifically educated in order to appear in public as royal wives.

Self-Mummification

The early Chinese believed that the soul was composed of multiple parts and after death, these parts dissipated, therefore never perpetuating the existence of the deceased. The only way to keep them together and thus continue (living) in a spiritual form was to leave the body intentionally - requiring awareness at the moment of death. Some Ch’an monks died and then naturally mummified in meditative posture, and it was believed that they had accomplished this feat. Many Chinese ideas entered Japan and were absorbed by the Shugendo tradition. The monks who chose to mummify themselves similarly believed that they must be mindful when the transition from life to death began. Thus, they tried to accomplish a complicated and difficult process that many were unable to complete.