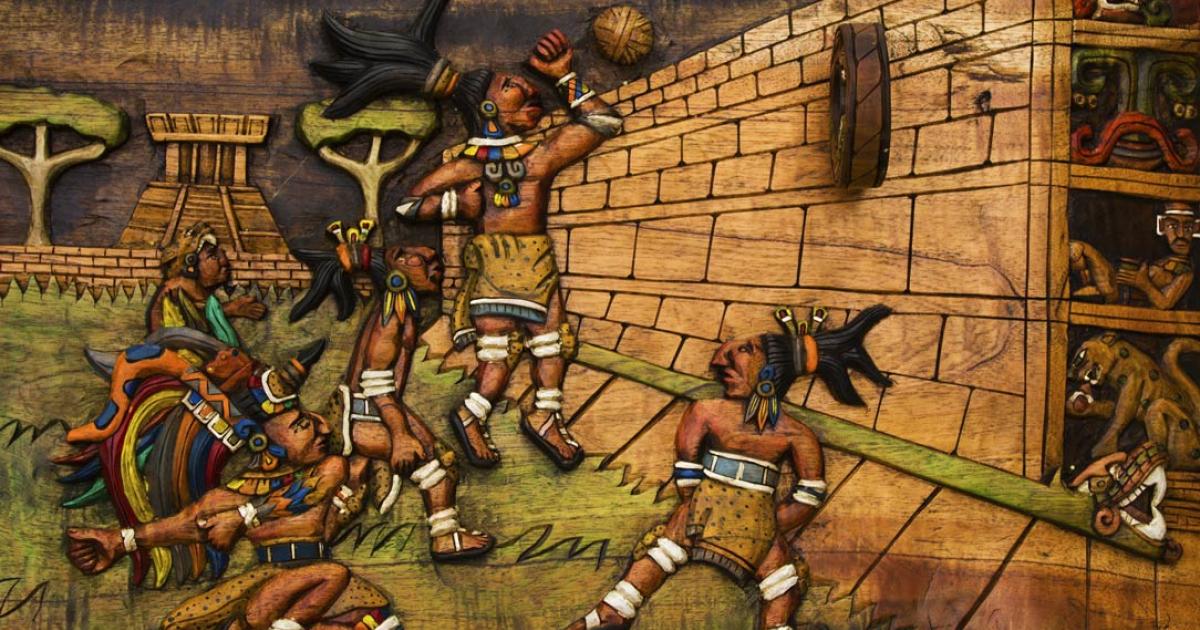

The Mesoamerican ball game is the oldest known team sport in the world. It was practiced by ancient Pre-Columbian cultures of Central America and played almost a millennium before the establishment of the first Greek Olympic Games. A fast-paced, often brutal game tied in with religious ritual, contestants often lost their lives and human sacrifices were regular occurrences.

From ancient times until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century, the sport was not just a game but a major part of Mesoamerican culture played by the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations.

Violence in the Mesoamerican Ball Game

To the Maya people, it was known as Pok a Tok, to the Aztec it was Tlachtli. Today it is called Ulama. The Mesoamerican ball game was a game where the action reached unimaginable levels of violence even by today’s standards. Serious injury was common as players dove onto stone courts to keep a ball in play and would end the game bloodied and bruised. When the high-speed movement of a heavy flying ball hit a player, it could cause internal bleeding to unprotected body zones and sometimes even death.

- Ancient Ball Courts Found in Mexico Rewrite Deadly Ballgame’s History

- 4 Billion People Can’t Be Wrong: The Record-Shattering Popularity of Football, an Ancient Game

- Playing Ball in Ancient Belize: 1,300-year-old Stone s Depicting Mayan Ballplayers Revealed

Ball player disc from Chinkultic, Chiapas. (LRafael /Adobe Stock)

The Mesoamerican Ball Court

Believed to have extended as far south as Paraguay and north into present day Arizona, the earliest known Mesoamerican ball court is Paso de la Amada in Mexico, which has been radiocarbon dated to around 3600 years old. This places it historically between the Mokaya and Olmec cultures and only a few hundred years after the early hunter-gatherers had settled into stable residential communities.

The oldest example of a ball court found in the Mexican highlands was identified in 2020. It is a ball court at Etlatongo, in the mountains of Oaxaca, southern Mexico and was built in about 1374 BC.

Roughly 1,300 Mesoamerican ball courts have been discovered and almost all the main Mesoamerican cities of antiquity had at least one. The Classic Maya city of Chichen Itzá had the largest – the Great Ballcourt, which measures 96.5 meters long (315 feet) and 30 meters wide (98 feet).

By comparison, the Ceremonial Court at Tikal (in modern day Guatemala) is 16 meters by 5 meters (52.49 by 16.4 feet) - smaller than a tennis court. The Olmec courts, on the other hand, were the size of a modern day football field and when seen from an aerial view, look like a capital “I” with two perpendicular end zones at the top and bottom.

They were lined with stone blocks and played on a rectangular court with slanted walls. These walls were often plastered and brightly painted. Serpents, jaguars, and raptors were depicted alongside images of human sacrifice - suggesting a connection to the divine.

The ball game court of Chichen Itzá. (lesniewski /Adobe Stock)

What were the Rules of the Ancient Mesoamerican Ball Game?

The exact rules of the game are unknown since the evidence available is garnered from the interpretations made from sculptures, art, ball courts, and glyphs. Some interpretations suggest that players were spread out along the court and the ball was passed at a fast rate. Teams seemed to vary in size from two to six players, and the object was to hit a solid rubber ball across a line.

On each side of a playing alley there were two long parallel walls against which a rubber ball was resounded and bounced from each team. This is similar to the game of volleyball except for the fact that players had to use their hips to return the ball and there was no net (the ball had to cross a line). The ball also had to be kept in motion, without touching the ground, and in some versions of the game it could apparently not be hit with hands or feet.

Later on, the Maya culture added two stone hoops or rings in the center of the court on either side. When a player did manage to get a ball through a ring, that usually ended the game. Points were also scored when opposing ball players missed a shot at the vertical hoops placed at the center point of the side walls, were unable to return the ball to the opposing team before it had bounced a second time, or allowed the ball to bounce outside the boundaries of the court. The team with the most points won.

Stone hoop on the Mesoamerican ball court at Chichen Itzá. (Matyas Rehak /Adobe Stock)

Equipped to Play a Dangerous Game

The large rubber ball could weigh up to three to eight pounds (1.36-3.63 kg.) and had a diameter around 25 to 37 centimeters (10 to 12 inches). This was about the size of a basketball, but the ball was more solid on the inside and could weigh a lot more. Because of this, it could inflict major bruises and if it hit someone in the wrong place hard enough, being struck with the heavy sphere could kill them.

Players eventually began wearing equipment to prevent severe injury. The needs and style of this equipment varied over time, but most commonly headdresses or helmets were worn to protect the head, quilted cotton pads covered the elbows and knees, and stone belts known as yokes were worn around the waist or chest. These yokes or “yugos” were used to hit and pass the ball and were elaborately decorated.

Figurine of a ball player wearing thick padded clothing (Wolfgang Sauber/CC BY SA 3.0)

Religious Aspects to the Ball Game

The Mesoamerican ball game has its origin in the cosmos and religious beliefs of the pre-Hispanic peoples. The most common interpretation saw the ball and its movement in the court paralleling the movement of the heavenly bodies in the sky. The game was viewed as a battle of the sun against the moon and stars - representing the principle of lightness and darkness.

If a game had particular religious importance, the losing team could be sacrificed. In illustrations from Pre-Columbian books such as the Codex Borgia and on carved stone friezes decorating the walls of ballcourts at the sites of Chichen Itza and El Tajin, the decapitation of one team captain by the other, or by a priest, is clearly depicted. The sacrifice of ball-players was intimately related to the celestial cycle of the sun and moon, for both the Maya and Aztecs, as was the game itself.

One of the most important episodes in the Popol Vuh (Maya creation myth) mentions two sets of important gods going down into the Underworld to contest with Lords One and Seven Death, the gods of the Underworld, and afterwards being killed and transformed into celestial bodies. The sacrifice of losing teams in the ball game was a reaffirmation of this for the Maya culture, and an aspect of a contract with the Underworld which allowed the sun and moon to rise every day so long as the sacrifices were made.

When the Spanish arrived in central Mexico in the 16th century, priests and conquistadors recorded their impressions of the Mesoamerican ball game. They found that among the Aztec there was a strong connection between the ball game and beheadings. Hernando Cortez ascribed a map of Tenochtitlan and labeled the ball court as Tzompantli (the Aztec word meaning “skull rack”). At this specific court thousands of skulls were found.

The Spanish would go on to ban the game due to its pagan connotations, ending thousands of years of the sport’s tradition.

- Archaeologists uncover ancient Maya ball court used as a ritual centre

- 3,000-Year-Old Ball Game Where Winners Lost Their Heads Is Revived in Mexico

- Ancient Pedigree of the Open Championship: Golf’s Long History and Hidden Beginnings

Ulama – A Modern Take on the Ancient Game

But today, people in Mexico still play a variant of the game that their ancestors once did. Called Ulama, it is a game played in a few communities in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. Ulama de Brazo is played in northern Sinaloa. Two teams of three face each other, and instead of their hips, players hit the ball with their forearms, which are protected by padding.

Ulama de Cadera is found in the south of Sinaloa. In this version of the ball game, teams tend to be made of five or more and in this case, the traditional hip is used to move the ball.

Another version of the game, Ulama de Palo, is different in that the players wield a wooden racket. This particular game was a relic of the past until it was revived in the 1980s.

Modern day Pok-ta-pok players in action. (CC BY SA 2.5)

Top Image: Representation of the ancient Mesoamerican ball game being played on the Great Ballcourt at Chichen Itza. Source: pop_gino /Adobe Stock

References

"The Mesoamerican Ball Game." Bouncing-Balls. http://www.bouncing-balls.com/timeline/ballgame.htm

"Pok-A-Tok: The Sacred Ball Game of the Ancient Maya." Examiner.com. http://www.examiner.com/article/pok-a-tok-the-sacred-ball-game-of-the-ancient-maya

"Mesoamerican Ball Game." http://linux1.tlc.north.denver.k12.co.us/~gmoreno/gmoreno/Mesoamerican_Ballgame.html

"Ulama - Mesoamerican Ballgame | DonQuijote." DonQuijote. http://www.donquijote.org/culture/mexico/sports/the-mesoamerican-ballgame-ulama

"The Mesoamerican Ball Game." Everything2. March 16, 2002. http://everything2.com/title/The Mesoamerican ball game

"A Comparison of Mayan and Aztec Ball Games." A Comparison of Mayan and Aztec Ball Games. April 22, 2014. https://mesoamericangaming.wordpress.com

Berkowitz, M. (n.d.). The Mesoamerican Ball Game. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4uNfzBEMXw

It would be nice to see how

Permalink

It would be nice to see how some of today's international pro footballers would cope with even ten minutes of this! No rolling around clutching shins if you might have your head whipped off!

Mesoamerican ball game

Permalink

I am doing a project on the differences in the Mayan and Aztec versions of the game. I would love it if I could interview you to get more information on the game. I understand if you don't want to do the interview, but I would appreciate any response. Thanks.

Hello Caleb,

Permalink

In reply to Mesoamerican ball game by Caleb Douglas (not verified)

Hello Caleb,

Thank you for your comment. The author no longer writes for Ancient Origins and as such is not available for interview, however if you’d like more information feel free to contact me at lizleafloor(at)ancient-origins.net , or you can search our site (search bar top left) for articles and information on the Maya and Aztec ball games.

All the best,

Liz

Questions

Permalink

In reply to Hello Caleb, by lizleafloor

Hello Liz,

Thanks for the response and I sent an email to you.

Sincerely,

Caleb Douglas

It's a great game and I am

Permalink

It's a great game and I am truly interested. My favorite teacher Mrs.Miller is making me do a wonderful movie about it.