Fiery Illusions of Rock Carvings: Prehistoric Movies

A virtual reality investigation of prehistoric rock art has concluded that flickering firelight may have been used to animate a selection of engraved rocks discovered in France. This could mean that this rock art was used as a form of entertainment, making them the first cartoons in history or even early examples of prehistoric cinema.

The Montastruc Rock Shelter and Finding the First Cartoons

Back in 1866, the French engineer Peccadeau de l’Isle was working on a rail project near Toulouse, when he decided to conduct excavations near Bruniquel on the banks of the River Aveyron in southern France. A lover of archaeology, within the Abri Montastruc rock shelter he unearthed a fascinating find known as the Swimming Reindeer of Montastruc, a 13,000-year-old Magdalenian sculpture created out of a mammoth tusk.

Alongside apparent examples of the first cartoons in history, Peccadeau de l’Isle unearthed the Swimming Reindeer of Montastruc – seen here - at the same site. (British Museum / CC BY 2.0)

Carved during the last Ice Age, this sculpture depicts two swimming reindeer and was included in the BBC’s A History of the World in 100 Objects. This stunning artifact was discovered after Peccadeau de l’Isle had patiently excavated 7 meters (23 ft) of material. Along with the Swimming Reindeer, de l’Isle unearthed various examples of prehistoric art, including 50 limestone engraved stones, known as plaquettes, a form of portable art, covered in representations of animals. These are now curated by the British Museum in London, and can be seen online at their website.

- Oxygen Deprivation Led To Altered States For Subterranean Artists

- Discovered! An Ancient Mongolian Stone Selfie!

This portable rock art is believed to have been created by Magdalenian people, early hunter-gatherers who lived between 23,000 and 14,000 years ago, a time of very cold conditions described as a near-glacial climate, and abundant food allowing for leisure time. In fact, the “Magdalenian era saw a flourishing of early art, from cave art and the decoration of tools and weapons to the engraving of stones and bones,” highlighted a press release from the University of Durham.

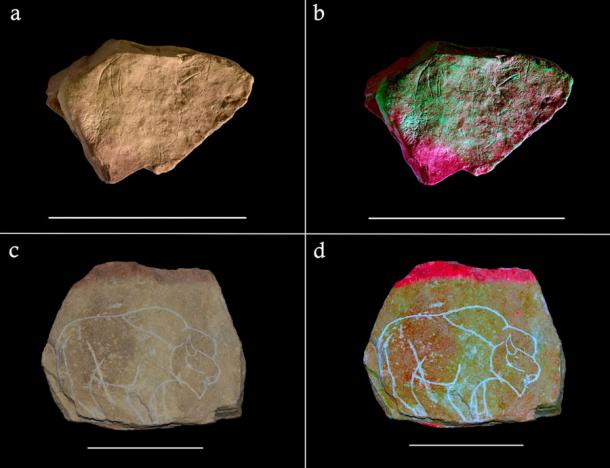

Photographs and digital tracings of two plaquettes from Montastruc. (Needham et al. - PLOS ONE / CC-BY 4.0)

High-Tech Analysis of First Cartoons

Created using stone and flint blades to etch into the rock surface, some of the engraved stones depict animals such as chamois, red deer, horses, reindeer or even ibex. Although discovered in the 19th century, there were still some unanswered questions. This portable rock art is however now located at the British Museum, far from its original context, which makes research all the more difficult.

Some of the stones showed evidence of heat damage consistent with having been exposed to fire, such as pink heat damage along the edge of some of the stones. Researchers at the Universities of York and Durham decided to delve further using experimental archaeology to discover if this heat damage had happened later or if it was part of the creative process which made these incredible examples of prehistoric rock art.

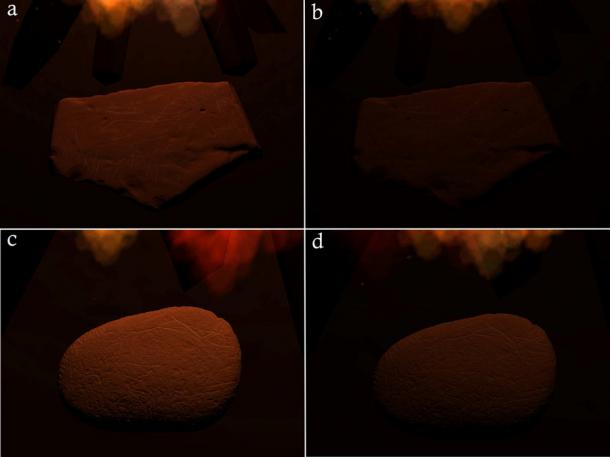

Using virtual reality software and a series of replica plaquettes, they began a series of experiments at the York Experimental Archaeology Research (YEAR) Centre in order to understand how the stones could have ended up with heat damage. In order to compare the resulting heat patterns, some were positioned as if used for practical ends, such as being used as part of the hearth, while others were buried to recreate accidental exposure long after they were originally etched. They even placed some near the hearth, as if the firelight was used purposefully to view them.

“It has previously been assumed that the heat damage visible on some plaquettes was likely to have been caused by accident, but experiments with replica plaquettes showed the damage was more consistent with being purposefully positioned close to a fire,” explained Dr. Andy Needham from the Department of Archaeology at the University of York in the United Kingdom and lead author of the study.

The research project concluded that the art had been repeatedly placed in a circle near the fire, while being created or viewed. The heat damage allowed them to understand how the portable rock art would have been positioned. Their results were published on April 20th in the journal PLOS ONE, in an article entitled Art by firelight? Using experimental and digital techniques to explore Magdalenian engraved plaquette use at Montastruc (France).

The research team made replicas of the 50 limestone plaquettes and analyzed the damage caused by heat exposure. (Needham et al. - PLOS ONE / CC-BY 4.0)

Animating Rock Art to Create the First Cartoons in History

Continued experiments using virtual reality software recreated the way in which the etched stones would have been seen in situ by the light of the fire thousands of years ago. Under these conditions, the researchers were surprised to witness the way in which the flickering firelight combined with the uneven rock surfaces to generate movement within the ancient rock art.

This virtual reality and simulated firelight “brought the engraved animals to life with the roving firelight and shifting shadows giving the impression that the animals were subtly moving,” explained Wisher and Needham in an article published by the Bradshaw Foundation.

“You can see for example a plaquette with several horses on it, and as the light flickers across the surface you see different forms kind of emerging, popping in and out of your perception, and it creates a kind of cool narrative of horses moving across the surface of the rock,” explained co-author Izzy Wisher, a PhD student at University of Durham in Smithsonian Magazine.

“Creating art by firelight would have been a very visceral experience, activating different parts of the human brain,” explained Needham in a University of York press release. “We know that flickering shadows and light enhance our evolutionary capacity to see forms and faces in inanimate objects and this might help explain why it's common to see plaquette designs that have used or integrated natural features in the rock to draw animals or artistic forms.”

The use of 3D scans and virtual reality revealed the way the different rock carvings could have been animated using flickering firelight. Could this be the first cartoon in history? (Needham et al. - PLOS ONE / CC-BY 4.0)

Using Visual Trickery to Bring Rock Art to Life

Could it really be true that these ancient rock carvings were actually used as a form of prehistoric animated cartoon? This isn’t the first time that researchers have found evidence for the origins of cinema in rock art, evidenced in the use of animation, shadow puppetry, special 3D effects and even visual trickery in order to bring rock art and its narratives to life. “It seems they were kind of playing around with this effect of the light to create these animated forms of art in the Paleolithic world,” highlighted Wisher in Smithsonian Magazine.

- Lascaux Cave and the Stunning Primordial Art of a Long Lost World

- ‘Unbiased’ Computer Software Learns To Decipher Australian Rock Art

Back in 2012, Marc Azéma and Florent Rivère published a paper in Antiquity which looked at 53 examples of cave art dating back to 30,000 years from within a selection of caves. The rock art within the famed Lascaux Cave in southwestern France is a case in point. Here animals, and especially horses, are drawn with various heads, legs or tails. “When these paintings are viewed by flickering torchlight the animated effect achieves its full impact,” explained Azéma.

This research provides a window into life in prehistoric times thousands of years ago. “Our findings reinforce the theory that the warm glow of the fire would have made it the hub of the community for social gatherings, telling stories and making art,” explained Wisher, co-author of the study. “This feels really human to me in a powerful way,” concluded Needham

Top image: Photo showing replica rock art etchings by firelight. Source: Needham et al. - PLOS ONE / CC-BY 4.0

By Cecilia Bogaard