The Untold Story of Walpurga Hausmannin: An Infamous German Witch

The legend of Walpurga Hausmannin is one of the scariest witch stories in the world. It is told as a tale of one of the most horrible killers in German history. However, the story seems to be half-truth and half legend. It also holds an unsolved mystery related to one of the darkest human practices.

Her exact birth date is unknown, but she was born between 1510 and 1527. For most of her life, she wasn't a particularly well-known person, but in the 16th century witch hunts she became a victim of terrible tortures and a trial which ended before it had even started.

Torturing accused witches, 1577. (Public Domain)

Killer Witch or Unstable Woman?

Walpurga worked as a maid for many years. She seems to have been a respected and valued worker - there are no stories about bad behavior until later in her life. Who could have imagined that she would be accused of witchcraft, vampirism, and murdering children?

The accusations took place in 1587, when she was an older woman. It is known that when Walpurga was accused, she was already a widow. There is no information about her having children. She lived in poverty, and perhaps hoped to die of old age, but instead she died in one of the most famous witch trails in German history.

1627 engraving of the malefizhaus of Bamberg, Germany. This is one location where suspected witches were held and interrogated. (Public Domain)

It is said that Walpurga’s confession was not typical or similar to others. She said a lot - much more than she was expected to. She was tortured and began to speak. This was probably in an attempt to end her suffering. She was aware that there was no other option because the intensification of the tortures showed her that she would not survive her trial. Therefore, she started to explain things the best she could.

- Gone and Forgotten: The Sad Fate of the Witches of Prussia

- Pointing to Witchcraft: The Possible Origin of the Conical Witch's Hat

- The Malleus Maleficarum: A Medieval Manual for Witch Hunters

First of all, she claimed that just after she was widowed in 1556 she had sex with a demon named Federlin. When he returned the next night he promised to save her from poverty, but she had to do some things for him. The first thing she had to do was swear and contract herself to Satan. When she agreed, Federlin apparently took her to Lucifer, who was described by Walpurga as a tall man with a long grey beard. She said that he reminded her of a great prince due to his rich jewelry and behavior. When he confirmed her contract, he invited her to drink wine, eat roasted babies, and have sex. She said that she also joined the ritual of despoiling the Blessed Sacrament, which she had stolen from the church.

“Teufelsbuhlschaft” (Sex with the Devil) (c. 1489) by J. Otmar. (Public Domain)

According to Walpurga, the demon gave her an ointment which she used to murder people and animals. She claimed that he visited her regularly to have sex, even while she was in prison. With his guidance, she decided to murder 40 children before they were baptized, and then sucked their blood. She explained that she used their bones and hair for sorcery and had eaten the bodies of the children she killed.

She was sentenced to death as a result of these confessions. Walter Stephens wrote about her execution in his book:

“On 20 September 1587, Walpurga Hausmannin, a licensed midwife practicing at Dillinged in the diocese of Augsburg in southern Germany, was burned at the stake as a witch. Walpurga confessed to a long list of maleficia, as deeds of harmful magic were called. Most of these were related to her profession as a midwife; in twelve years she had supposedly killed forty-one infants and two mothers in labor. But she also confessed to attacking other people: Georg Klinger's small son, the wives of the governor and town scribe, Hans Striegel's cloistered daughter, and Michel Klingler. Of these five people, three were not expected to live, according to the contemporary account of Walpurga's trial. Nor was her maleficence limited to people, it was claimed: she was blamed for the death of nine cows (although “she confesses that she destroyed a number of cattle over and above this”), a horse, and an unspecified number of pigs and geese. And she attacked crops, causing hailstorms “once or twice a year”.”

Walpurga’s right hand was cut off before she was burned on the stake. On her way to her death, she was further mutilated and tortured in public.

- Agnes Waterhouse: The First Woman Executed for Witchcraft in England

- Witch Familiars, Spirit Guardians and Demons

- The Biblical Witch of Endor: Contacting the Spirit of a Prophet

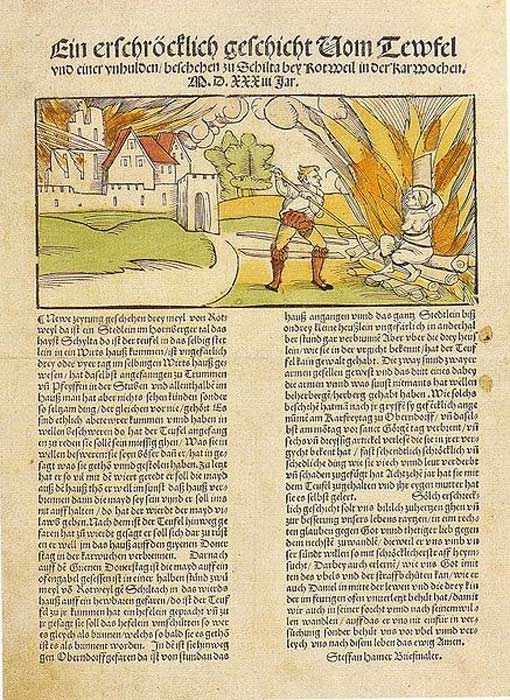

1533 account of the execution of a witch who was charged with burning the German town of Schiltach in 1531. (Public Domain)

Who Was Walpurga?

It is difficult to discover who Walpurga really was, but the evidence against her is not very convincing today. In fact, her own words were the strongest pieces of evidence in her conviction. However, she confessed all of her crimes under torture. Was she mentally ill? A victim of anti-witch propaganda? Or was she really a serial killer?

The last option on this list actually seems to be the most unlikely. When Walpurga was in prison, she was tortured without mercy. As was common during witch trials in that part of the world, the accused woman was tortured until she admitted that she was a witch. Scholars say that the story of Walpurga is “sadly typical of witchcraft trials.” It was common to accuse an old woman who had her own way of living - which was not always understood by younger generations. They were often attacked and nobody protected them.

Witch burning in Derenburg (Reinstein county) 1555. (Public Domain)

Walpurga’s ashes were scattered in the river - she didn't receive the privilege of being buried. Like many other women who were judged and executed due to the suspicions of a blindly religious society, she died without the right to have a real trial; one which could have used facts, not superstitions, to decide her fate.

Top Image: Detail of an execution scene from the chronicle of Schilling of Lucerne (1513) illustrating the burning of a woman in Willisau (Switzerland) in 1447. Source: Public Domain

References:

Walter Stephens, Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief, 2002.

The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed, by Brian P. Levack, John E Green, 2003.

Famous Witches - Walpurga Hausmännin (? - 1597), available at:

http://www.witchcraftandwitches.com/witches_hausmannin.html

Judgment on the witch Walpurga Hausmännin, available at:

http://courses.washington.edu/hsteu305/Walpurga%20Hausman.PDF

Comments

"...a barrier to the oncoming patriachal society and to christianity taking hold over Europe."

My friend, by the 1500s both of these had been firmly in place for centuries.

These women were our healers both physical and spiritual.They had to go didn’t they as they were a barrier to the oncoming patriachal society and to christianity taking hold over Europe.

The excerpt says “Walpurga confessed to a long list of maleficia, as deeds of harmful magic were called. Most of these were related to her profession as a midwife; in twelve years she had supposedly killed forty-one infants and two mothers in labor.” Infant mortality rate in the old world was about 30%-50% so her 41 infants are probably all due to natural causes/illnesses of the time. That being said, I’m sure the local people knew the infants she was talking about. Who wouldnt know that their neighbor had 10 kids but only 4 survived? or that another neighbor had 6 kids but only 3 survived? Or that you lost a number of your own children?

--Still learning--

So she maintained she killed more than 40 children – did she identify them by name and where they lived? Were any of these claims actually verified? Were any of the children who had been murdered by her, according to her confessions, even reported missing?

I bet at the time, no one even cared enough to verify what she said. As long as they had something to burn, did they even need to? Anyone would confess anything under torture – anything, just as long as they could stop the pain. Believing otherwise is pure stupidity.

- Moonsong

--------------------------------------------

A dreamer is one who can only find his way by moonlight, and his punishment is that he sees the dawn before the rest of the world ~ Oscar Wilde

This is great context for Goethe's Faust.