Old Maps and Hi-Tech Scans Reveal A Lost City’s Watery Past at Jerash Jordan

Comparing high definition photography and state-of-the-art airborne laser scans with clues from ancient artifacts, archaeologists in Jordan have reconstructed the ancient waterways of a hidden urban landscape covered with thousands of years of human development.

Cupping water from fish-rich fresh streams and rivers, modern humans (Homo sapiens) have hunted and gathered on this planet for over 200,000 years. Approximately 10,000 years ago, folk adopted an agrarian way of life and the success of new villages and cities depended greatly on fresh water supplies as pathogens transmitted by contaminated water were a serious health risk for these sedentary agriculturists.

- 9,000-Year-Old Skeletons Found in Jordan had been Dismembered, Sorted, and Buried in Homes

- Set of 70 Metal Tablets May Have the Earliest Written Account and Depiction of Jesus

- Garshu, Gerasa, Jerash: the Everchanging City of the Ancient World

A Multi Discipline and Tech Data Dump

It was with a goal of mapping fresh water sources and their channels that Jordanian archaeologists teamed up with Søren Munch Kristiansen from the Centre for Urban Network Evolutions and GeoScience at Aarhus University, Denmark, as well as David Stott from Archaeological IT and Moesgaard Museum. These scientists recently published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) detailing how for the first time archaeologists have successfully mapped the ancient city Gerasa (modern-day Jerash in northern Jordan) “with extreme accuracy and precision.”

Speaking of their methodology, geoscientist David Stott of Aarhus University told reporters:

The novelty of our approach is that it integrates World War I photos, contemporary mm-precise 3D-laser scanning, and decades of scattered archaeological excavation data to produce a detailed map of how an entire ancient city in the Middle East appeared before modern destruction and urban encroachment began.

Views over the Oval Piazza at Jerash from 1898 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-matpc-04523) (A) and 2015 (Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Excavation Project) (B). Note the extensive clearance of rubble, construction of tracks, and reconstruction of ruins in foreground and expansive urbanization in background in B. (Image: David Stott et al/PNAS)

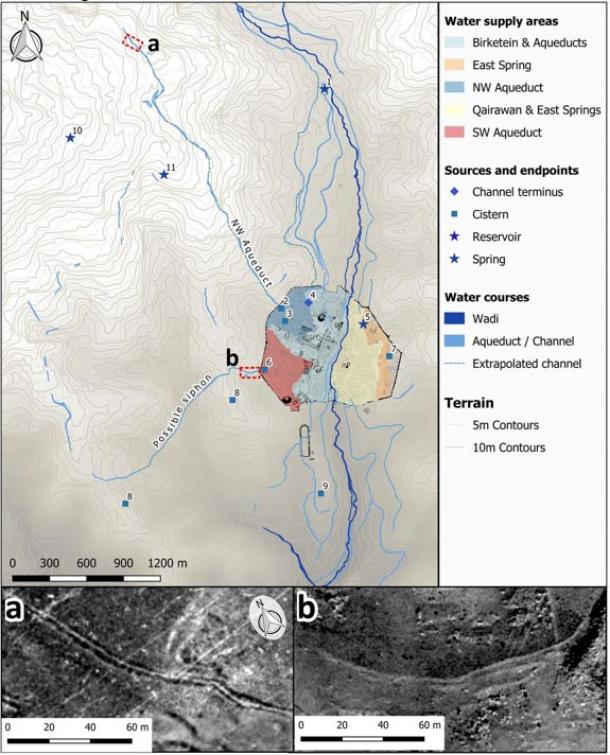

By combining LiDAR data from the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, historical photographs dating back more than a century and satellite images documenting modern day development at Jerash, previously unknown structures were discovered like “possible aqueducts, water channels, springs, and cisterns.” This told David Stott that water management in ancient Gerasa “changed profoundly over time, due to changing settlement patterns and management of the hinterland.”

Urban expansion in and around Jerash is dramatic. Since 1953 much of the area around the city has been developed. Within the city walls, the eastern half of the city is nearly totally overbuilt. (Image: David Stott et al/PNAS)

Peeling Back the Layers of Gerasa

In August 2015, an archaeological excavation team from the University of Jordan unearthed two human skulls dating to the Neolithic Period (7500–5500 BC) at a site in Jerash. Many European explorers visited the lost city of Gerasa in the 19th and 20th centuries. The first official archaeological excavation, however, took place in 1907 which uncovered “a splendid mosaic, which today is spread across the world in a number of collections, including the Pergamon Museum in Berlin,” according to a Science Nordic article. Gerasa was first formally excavated in the 1920s and 1930s by Yale scholar C. H. Kraeling who headed up an American-British archaeological mission which established that Gerasa was an “important city in the eastern Roman Empire covering an area of approximately 90 ha, encircled by more than 4 kilometers of city walls.”

- Unexpected Statues of Mythological Goddess Unearthed in Jordan

- Mysterious Ancient Wall Extending Over 150km Investigated in Jordan

- Experts Uncover Rare Mosaics Showing Biblical Scenes in Ancient Synagogue in Galilee

A colonnade leading to a modern part of the city of Jerash. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Having been destroyed by a devastating earthquake in 749 AD lifestyles diminished and it was not until the Middle Islamic period (starting in the 12th century AD) settlement started again. Even though over the last century many teams of archaeologists have worked in Gerasa, large parts of the city remained unexplored and were being threatened by looting and modern developments.

A Human and Environmental History Revealed

These new archaeological finds indicate that environmental changes took place around ancient Gerasa between the 5th to 8th centuries AD, and “monumental water cisterns were found closed off and falling out of use indicating urban decline or at least significant changes in the management of public works, while at the same time domestic habitation flourished in the Late Antique and early Islamic periods” according to the PNAS paper.

David Stott said these new results reveal the various ways water was managed in the hinterland around Gerasa and while these changes had traditionally been attributed to the devastating earthquake of the 8 th century, the new data suggests that changes began “centuries earlier than previously thought,” and were caused by climate change.

Water sources and infrastructure at Jerash mapped from the remotely sensed 100-y data record, showing supply channels, probable supply areas calculated from the 1953 DTM. (Image: David Stott et al/PNAS)

Archaeologists are in a race against time, and the environment, to record and interpret past societies before the historical remains are destroyed. Non-invasive mapping archaeology is a “crucial part of this endeavor, allowing us to turn back time and document destroyed and lost monuments that connect us with the past,” said David Stott.

Top image: The ancient city of Gerasa with the modern city in the background. (Public Domain)

By Ashley Cowie