Clash of Titans: The Roman-Etruscan Wars of Ancient Italy

The Roman-Etruscan Wars represent a significant chapter in the ancient history of ancient Italy, marking the clashes between the burgeoning power of Rome and the advanced civilization of the Etruscans. Spanning the centuries, these conflicts emerged from territorial disputes, cultural differences, and ambitions for dominance in the Italian peninsula. The interactions between Rome and Etruria shaped the political landscape of the region, leading to military confrontations that led to the ultimate demise of the Etruscans. These wars saw Rome’s rise to almost unparalleled levels of fall and the Etruscan’s fall from greatness.

- Early Copper Age Tombs Unearthed from Italian City

- Untouched 2,600-Year-Old Fully Intact Etruscan Tomb Uncovered in Italy

The Rise and Fall of Empires: Roman-Etruscans Wars

The Romans need no introduction but for many of us, the Etruscans might. The Etruscans were a civilization that flourished in ancient Italy from around the 8th to the 4th century BC. Originating in the region known as Etruria, encompassing modern-day Tuscany, parts of Umbria, and northern Lazio, the Etruscans left behind a rich legacy of art, architecture, and religious practices.

Their origins are debated among scholars, with theories suggesting connections to indigenous Italian populations and influences from Anatolian and Aegean cultures. The Etruscans developed a distinctive culture characterized by urban centers, sophisticated craftsmanship, and a complex religious and funerary belief system.

Etruscan society was organized into city-states ruled by aristocratic elites, known as lucumones, who governed with the support of councils and assemblies. The Etruscans were skilled traders and seafarers, establishing trade networks across the Mediterranean and importing luxury goods such as Greek pottery and Near Eastern artifacts.

- Mysterious Origins of the Etruscans: DNA Study Solves the Riddle

- Tarchon and Tyrrhenus: The Etruscan Romulus and Remus?

Wall painting in a burial chamber called Tomb of the Leopards at the Etruscan necropolis of Tarquinia in Lazio, Italy. (Public Domain)

Their artistic achievements, including intricate bronze works, vibrant frescoes, and ornate tombs, attest to their cultural sophistication and influence. Despite their prominence in ancient Italy, the Etruscans gradually succumbed to Roman expansionism, eventually assimilating into Roman society by the end of the Roman Republic.

The Origin of the Roman-Etruscan Wars

One of the biggest problems with covering the Roman-Etruscan Wars is that no one seems to agree on when they began or ended. This is because they took place incredibly early in Roman history and little information on the wars survives in ancient sources. We have a “rough idea” of what happened, but the details can be blurry.

Making things even more complicated, much of the information we can glean from the ancients includes a heavy dose of mythology - making it unreliable. Our best source is Livy, but he was writing on the wars four hundred years or so after they occurred, and his sources weren’t exactly reliable.

It’s generally accepted that the wars began around the beginning of the fifth century BC. Many modern historians put the date at 509 BC while Livy believed it was 483 BC. But the ancient sources go back even further.

First War- Romulus vs. the Etruscans

According to legend, the Romans’ first clash with the Etruscans occurred during the 8th century BC. During the reign of Rome’s first king, Romulus, an Etruscan people called the Fidenates are said to have become concerned that Rome was growing too quickly and was going to become a threat.

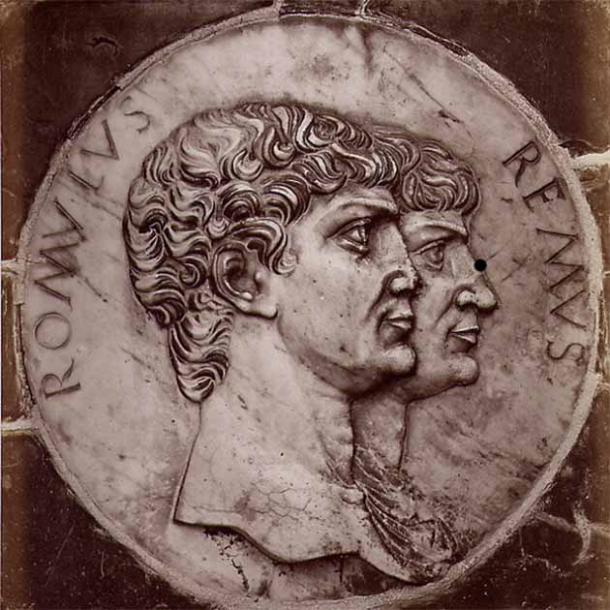

Romulus and his twin brother Remus from a 15th-century frieze. (Public Domain)

They began attacking Roman lands, which led Romulus to lead an attack on the city of Fidenae itself. The attack was a success but caught the attention of the Veientes of nearby Veii, another Etruscan people. They also decided to raid Rome’s lands, soon returning home with plenty of booty.

Romulus didn’t take this lightly and retaliated, meeting the Veientes outside of their home city. The Romans won the initial battle but lacked the manpower to lay siege to Veii.

At somewhat of a stalemate, the Veientes decided to sue for peace. An agreement was reached, and a one-year peace treaty was signed on the understanding that the Romans would receive a chunk of Etruscan territory.

Second and Third Wars

This peace lasted into the seventh century BC and the reign of Rome’s third legendary king, Tullus Hostilius. This time the Romans were ganged up on by both the Fidenates and the Veientes, who according to Livy, had been stirred up by the dictator of Alba Longa, Mettius Fufetius. Mettius had recently been defeated by Rome and his kingdom turned into a vassal of Rome.

Tullus Hostilius defeating the army of Veii and Fidenae during the Roman-Etruscan wars, modern fresco. (Public Domain)

The plan was for the Etruscans to meet the Romans in battle and for Mettius and his men to betray the Romans, ensuring an Etruscan victory. However, due to a miscommunication, the Fidenates ended up retreating and the Veientes were defeated.

The third war came in the 6th century BC when Rome’s sixth king, Servius Tullius, decided to attack the Etruscans (seemingly for no other reason than the most recent peace treaty had expired). There are few surviving records of the war, but it would seem it was a clear victory for the legendary Roman king, who used his win to cement his claim to the throne.

Overthrowing the Etruscan Leaders of Rome

Despite the fact the Romans and Etruscans had already fought several times over the preceding centuries at some point it seems an Etruscan dynasty began ruling over Rome. We know this because Rome's seventh (and last) legendary king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was Etruscan by blood. His family hailed from Tarquinii, in Etruria.

In 509 BC Superbus was overthrown by prince Lucius Junius Brutus. In his place the republic commenced, and the first consuls were elected. Superbus then escaped to the Etruscans and asked the cities of Veii and Tarquinii for help. After centuries of losing both their pride and lands to the Romans, they were happy to step in.

The two Etruscan cities sent their armies to attack Rome but were defeated by the Roman army at the Battle of Silva Arsia. A triumph was then celebrated in Rome on 1 March 509 BC. According to Livy consul Valerius then led an attack on the Veientes, although it’s unclear if this was connected to the Battle of Silva Arsia or if there had been yet another dispute.

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus still wanted his throne back, however. His next stop was the Etruscan city of Clusium in 508 BC. Upon arriving he asked the city’s powerful king, Lars Porsena, for help. He readily agreed.

Porsena gave the Romans a run for their money. He took the fight straight to Rome and marched his army on the great city. As his army was preparing to cross the Pons Sublicius (one of the great bridges that led to Rome) the Romans burnt it down, stalling the Etruscan attack. Porsena responded by changing tactics and blockaded Rome.

Lars Porsena watches as Gaius Mucius Scaevola puts his hand into fire, which fooled Porsena into striking a peace deal with Rome. (Public domain)

It’s unclear how long the siege lasted, nor how it ended. A popular Roman story told how the Romans sent a young soldier, Gaius Mucius, to the Etruscan camp to assassinate Porsena. Porsena foiled the attempt on his life but was so impressed with the young man’s bravery that he decided to offer peace.

Etruscan ambassadors were sent to Rome, and it was agreed that a hostage exchange would be carried out and that Rome would return lands back to the Veientes that they had previously taken. It’s said that Porsena also demanded Tarquinius be restored to power but the Romans refused.

According to Livy, Porsena sent more ambassadors to Rome in 507 BC to request the former king be restored. The Romans refused and told Porsena to drop it unless he wanted another war. Porsena did indeed drop it and expelled the former Roman king from his lands.

How true this all is up to debate. The Romans believed everything above was historical fact, but many modern historians aren’t so sure. It’s thought that at least part of this war between Porsena and the Romans was to some extent mythical.

Weakening Etruscans

One thing is true, however. These losses against the Romans were taking their toll on the Etruscans. With each loss their dominance over Central Italy weakened. In 508 BC, following his negotiations with Rome, Porsena attempted to save face by attacking the Latin city of Aricia. He hoped that a victory there would distract from his expedition to Rome and make sure he remained Etruria’s most powerful king.

Unfortunately, things didn’t go his way. The people of Aricia immediately sought the help of the Latin League (an ancient confederation of Italian tribes) and the Greek city, Cumae. These reinforcements eventually handed the Arcician forces victory and according to Livy Porsena’s force was destroyed.

If defeat wasn’t embarrassing enough, Livy recorded that the few Clusians who survived the attack fled to Rome. Arriving as supplicants they were given a district of the city to settle in, later known as Vicus Tuscus.

The Etruscans now had powerful enemies on two fronts. Not only was Rome constantly growing in power but the Greek cities in southern Italy, Magna Graecia, were now causing the Etruscans problems. Maybe the Etruscans could have stood up against one of the powers, but competing with both would eventually prove to be too much to handle.

Box with scene depicting Roman hero Gaius Mucius Scaevola before the Etruscan king Lars Porsena (Public Domain)

The Fabian War of 484-476 BC

Following the truce of 508 BC there was a period of relative peace between the Romans and Etruscans. This ended in 484 BC when the city of Veii, with the help of other Etruscan cities, once again decided to pick a fight with Rome.

Initially, the Romans didn’t take the threat too seriously. They believed they had grown to a point where the Etruscans weren’t really a threat and were preoccupied with dealing with internal matters. The Romans only really started paying attention in 482 BC when the Veientine army attacked Roman territory and began ravaging its countryside. By 481 BC the Etruscans had made enough headway in the war that they were threatening to besiege Rome itself.

The Romans’ initial overconfidence proved to be a costly mistake. In 480 BC, with Rome being torn apart by internal conflicts, the Veientes decided to kick their war into high gear. What ensued was a great slaughter as the Etruscan army, led by the Veientes, clashed with the Roman army, led by its consols Marcus Fabius Vibulanus and Gnaeus Manlius Cincinnatus.

The Romans emerged victorious but not unscathed. Manlius was mortally wounded during the fighting and Fabius lost his brother, Quintus Fabius. The Etruscans managed to escape and despite leading his men to victory Fabius refused the honor of a triumph upon appearing before the Senate.

The Battle of the Cremera and Slaughter of the Fabians

In 479 BC the war was still raging. That year a powerful Roman family, the Fabii, approached the Senate and proposed their family take sole responsibility for fighting the war. The senate agreed and the Fabii took on the financial and military burden of the war. Overnight they became national heroes.

The next day the Fabii, numbering 306 and accompanied by the consul, marched out of Rome to cheers and headed north where they set up camp on the Cremera (a stream that ran for miles into Etruscan lands). From this base, the Fabii led countless successful raids into Veii territory, ravaging their lands. The Etruscans responded by attacking the Fabian post directly but were defeated when consul Lucius Aemilius Mamercus arrived at the last minute with his cavalry. The Veinetes army was forced to flee to the Saxa Rubra and sue for peace.

That peace didn’t last for long. Fighting broke out again in 477 BC with both sides raiding each other’s lands. Tiring of the stalemate, the Etruscans of Veii devised a plan to ambush the Fabians at Cremera. They launched their plan on 18 July 477 BC at the Battle of the Cremera.

The Battle of the Cremera, 477 BC. (Frans Vandewalle / CC BY-SA 2.0)

It was a bloodbath for the Romans. The Veientes were victorious and all the Fabii were killed. The family’s only survivor was Quintus Fabius Vibulanus, who was too young to fight and had had stayed in Rome.

The Senate sent its consuls to attack the Etruscan forces in revenge, but the Romans were once again defeated. The Veientes then marched on Rome and occupied the Janiculum (a hill in western Rome). There was more fighting and the Veientes eventually decided to leave Rome and focus on raiding its countryside. The war ended in 476 BC when a victory meant the Romans finally managed to force the Etruscans from their lands.

Etruscan Defeat

The Etruscan victory against the Fabii marked the beginning of the end for the Etruscans. For the rest of the fifth century BC, they struggled as they were constantly attacked on all sides. In the north, they had the Celts to deal with. They had not only taken some Etruscan lands, but they had also successfully conquered the eastern Italian coast adjacent to Etruscan territory. This cut the Etruscans off from the Adriatic Sea.

To the west, the Greeks of southern Italy had continued to grow in power and had won several big wins against the Etruscans. As the Etruscans weakened it was only a matter of time until the Romans came to settle things once and for all. While the Etruscans withered the Romans had taken the entire Latin League, which meant they controlled all the Latin cities in Italy. They were more powerful than ever before.

In 396 BC the Etruscans and the Romans once again went to war. The Romans, led by Marcus Furius Camillus, were victorious and took the great city of Veii. It was a defeat the Etruscans couldn’t recover from.

Painting titled: Triumph of Furius Camillus by Francesco Salviati. (Public Domain)

There were two major wars between the Etruscans and Romans during the fourth century BC. First, there was the Fighting at Sutrium, Nepete, and near Tarquinii from 389–386 BC. Second was the war with Tarquinii, Falerii, and Caere from 359–351 BC. Both continued the trend of Etruscan losses and the Romans growing in power.

By the third century BC, the Etruscans had lowered themselves to looking for outside help. In 298 BC they hired some Gallic allies and decided to invade Rome. Things backfired, however, when the Gauls decided attacking Rome was a bad idea and left the Etruscans to face the Romans on their own. Led by consul Marcus Valerius Corvus the Roman army journeyed to Etruria and began laying waste to the country.

These events led to the Battle of Sentinum in 295 BC. The Romans took on the combined might of the Etruscans, Umbrians, Gauls, and Samnites who had formed an intimidating coalition. Despite being severely outnumbered the Romans emerged victorious, smashing the coalition, and leaving the Etruscans without any allies.

Conclusion

The next few decades saw multiple Etruscan cities fall to the Romans. By 264 BC the last of the Etruscan resistance had been crushed. The Romans then did what they always did, assimilated their enemies into their culture. Rome, next to the Greeks and Carthaginians had become one of the Mediterranean's three ancient superpowers.

Few ancient powers could stand up to the Roman military machine and the Etruscans put up just about as good a fight as any. The legacy of these wars resonates in the cultural exchange, technological innovations, and societal transformations that ensued, laying the foundation for the emergence of Rome as a dominant force in the Mediterranean world.

Top image: In 477 BC, the Battle of the Cremera was fought between the Roman Republic and Veii, leading to the loss of Roman control over the river Cremera. This allowed Veientes to penetrate deeper into Roman territory. Source: Frans Vandewalle / CC BY-SA 2.0

References

Howells. C. 2024. The Etruscan-Roman Wars and the Crucial Role of Ancient Greeks. Available at: https://greekreporter.com/2024/03/11/wars-etruscans-romans-ancient-greeks/

Editor. 2021. How Did the Romans Conquer the Etruscans. Available at: https://www.dailyhistory.org/How_Did_the_Romans_Conquer_the_Etruscans

Cartwright. M. 2017. Etruscan Warfare. Available at: