New Evidence of Early Humans Crossing the Alps 45,000 Years Ago

Between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago, the lands of present-day Europe and Asia experienced a population exchange between Homo sapiens (modern humans) and Neanderthals, with the former steadily displacing the latter. New research just published in the journals Nature and Nature Ecology & Evolution offers fresh evidence about some of the migratory movements of humans during that period, showing that pioneering Homo sapiens groups crossed rugged the Alps and settled in northern Europe (specifically in modern-day Germany) approximately 45,000 years ago.

The discovery of evidence related to humans crossing the Alps is significant because it proves that Homo sapiens were present in central and northwestern Europe several thousand years before the last of the European Neanderthals went extinct in southwestern Europe, according to the authors of the Nature study.

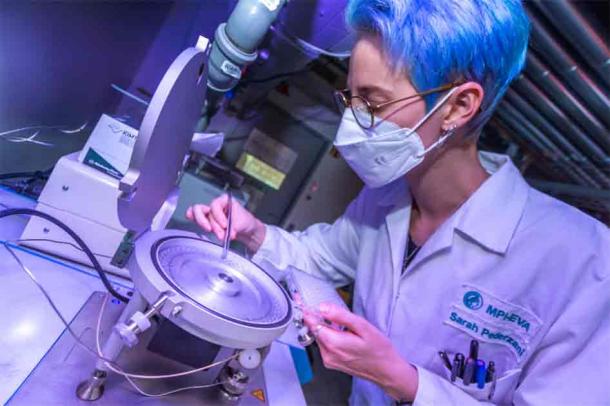

Proteomic extraction from archaeological bone fragments is performed in a sterilized environment to avoid modern contamination. (Dorothea Mylopotamitaki / CC-BY-ND 4.0 / Nature)

The Human Land Grab Inspired Humans Crossing the Alps

With the competition for land still strong 45,000 years ago, the earliest Homo sapiens groups in Eurasia would have had a strong incentive to migrate to locations where Neanderthal populations were scarce or non-existent. After successfully crossing the Alps, one of the places they occupied was in east-central Germany, near the village of Ranis in the German state of Thuringia. This is known because of the discovery of human skeletons buried in a cave known as Ilsenhöhle, and those remains have now officially been dated to 43,000 BC.

The cave site Ilsenhöhle beneath the castle of Ranis, where human skeletons dated to 43,000 BC were found. (© Tim Schüler TLDA / CC-BY-ND 4.0 / Nature)

As the researchers explain in their Nature article, the results of their study are consistent with the theory that multiple distinct human populations with unique cultures were dispersed far and wide and living in different areas in Europe 45,000 years ago. The prehistoric humans discovered in the cave in Ranis have been connected to the distinctive Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician (LRJ) toolmaking culture, which predominated in certain parts of Upper Paleolithic Europe and has been associated with both early humans and Neanderthals.

Excavating the LRJ layers 8 meters deep at Ranis was a logistical challenge and required elaborate scaffolding to support the trench. (Marcel Weiss / CC-BY-ND 4.0 / Nature)

Humans Could Survive the Cold, but Neanderthals Could Not

The revelation about humans crossing the Alps to reach Germany, and when Homo sapiens exactly this happened, is notable for yet another reason. It seems the climate in this area was unusually frigid at this time, and not particularly hospitable to hominin life. The existence of a human settlement that dates back to this cold era highlights the physical hardiness and cultural flexibility that gave Homo sapiens an advantage over their Neanderthal cousins, an advantage that guaranteed one species would endure while the other eventually went extinct.

- Study Tracks Neanderthal DNA, and It’s A Cross-Continental Odyssey!

- Amazing Things That the Neanderthals Did (Video)

The truth about the harsh conditions in Germany 45,000 years ago was discovered during tests designed to obtain stable isotopes measurements from 16 horse teeth recovered from Ilsenhöhle. The teeth came from equines that had been inside the cave, presumably in the company of humans, throughout the period from 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. These measurements inevitably vary based on climate-related factors, and the isotope contents of the teeth conclusively proved that the area around Ranis had experienced a deep freeze during this time frame.

“Directly dated H. sapiens remains confirm that humans used the site even during this very cold phase,” the authors of the stable isotope study wrote in their Nature Ecology & Evolution article. “Together with recent evidence from the Initial Upper Paleolithic [slightly later than 43,000 BC], this demonstrates that humans operated in severe cold conditions during many distinct early dispersals into Europe and suggests pronounced adaptability.”

The discovery that humans were living north of the Alps in 43,000 BC, or during a period known as the Middle-to-Upper Paleolithic transition, reveals how rapidly human beings were able to extend their territorial range after migrating from Africa to Eurasia. The Neanderthals were nowhere near flexible enough to match these movements, and yet were able to hang on in western Europe for a few thousand years after the earliest arrivals of Homo sapiens.

It is known that some interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals occurred between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago, which is why the genetic inheritance of people of European and Asian ancestry includes fragments of Neanderthal DNA. But the ability of prehistoric humans to survive in more geographically diverse locations, braving the elements in colder areas like east-central Germany, helped cause an inevitable separation between the two species that ultimately limited interbreeding opportunities (and doomed the Neanderthals).

After chemical preparation and purification, very small samples from animal teeth are loaded into the magazine of an isotope ratio mass spectrometer to obtain oxygen stable isotope ratios, which yield information about past climates that animals lived in. (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology / CC-BY-ND / Nature)

Sometimes Climate Mattered, and Sometimes it Didn’t

Previously, the geographical movements of the earliest humans to come to Eurasia from Africa were associated with warmer temperature conditions, not colder ones. “Prominent models have suggested that early range expansions of H. sapiens during the Late Pleistocene were linked to warm climatic phases that facilitated adaptation to higher latitudes,” the authors of the Nature Ecology & Evolution paper explained.

“Our results show that climatic conditions throughout the LRJ occupations, even during the earliest phase (between 48,000 and 45,000 years before the present) were characterized by temperatures substantially below modern-day conditions.”

Interestingly, there is yet another new paper, also published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, that examines the lives of the human settlers who arrived at east-central Germany after crossing the Alps so long ago. The researchers involved in this study looked more closely at the activities of these prehistoric humans and concluded that they would have spent short periods of time in this particular region, rather than settling down and living there year-round.

- Climate Change Played Cupid Between Neanderthals and Denisovans

- Tooth Enamel Reveals Differences Between Neanderthal and Human Survival Tactics

The ancient visitors to the cave known as Ilsenhöhle would have been small hunter-gatherer groups who would have followed migrating horse, rhinoceros and reindeer herds wherever they might travel, in order to secure food supplies for their people. The cave would have represented a stopover site, but because of the cold climate the visitors would have moved on after a few days to continue their nomadic wanderings.

Human bone fragment from the new excavations at Ranis. (Tim Schüler TLDA / CC-BY-ND / Nature)

Gaining the Survival Edge

Events that took place in Eurasia between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago ultimately sealed the fate of the Neanderthals, as they lost the competition for land and resources to Homo sapiens. The reasons for this outcome are complex, but as the studies of the prehistoric human remains found at Ranis have revealed, climate adaptability was undoubtedly one of the major factors that gave humans such a decisive survival advantage. Whether moving into areas that were excessively hot or excessively cold, human beings could handle the transition while their Neanderthal cousins could not.

Top image: Analysis of over 1,000 animal bones from Ranis showed that early Homo sapiens processed the carcasses of deer but also of carnivores, including wolf. Source: Geoff M. Smith / CC-BY-ND 4.0 / Nature

By Nathan Falde