The Exotic Menagerie: The Wild Animals Slaughtered in Gladiator Games

The ancient Roman gladiator games were a spectacle of blood and brutality that captivated audiences for centuries. While we may imagine sword-wielding gladiators fighting to the death in the arena, there was another element to these games that often goes overlooked: the use of exotic animals. From lions and tigers to elephants and bears, these majestic creatures were brought in from far-flung lands to add an element of danger and excitement to the games. But what was life like for these animals, and how were they transported and kept? This is the fascinating and often disturbing world of exotic animals in Roman gladiator games.

A History of Animals and the Roman Games

The gladiator games held at the Colosseum were all about one thing - propaganda. The entire purpose of these games was to show off the wealth, power, and generosity of the emperors who staged them. As such, the games had to be as spectacular as possible, and the stakes had to be raised repeatedly.

What better show of wealth and power than the staged hunting of exotic beasts most Roman citizens had never even heard of before, let alone seen? Animal hunts soon became a popular event at the Colosseum, second in popularity only to the gladiator fights.

But these hunts actually predated the Colosseum’s inauguration in 81 AD. Public spectacles of wild animals either being hunted or forced to fight each other were common throughout Roman civilization. The first record of such an event dates back to 251 BC when 142 elephants were shown off to celebrate a famous victory against the Carthaginians. Once the show was over, the elephants had outlived their usefulness to the Romans and were slaughtered.

Over time, these events became more sophisticated. In 186 BC Marcus Fulvius Nobilor (a Roman consul and general) held the first known event where lions and panthers were used in an arena hunt. The crowd lapped it up and these hunts, known as venationes quickly became commonplace in Roman games.

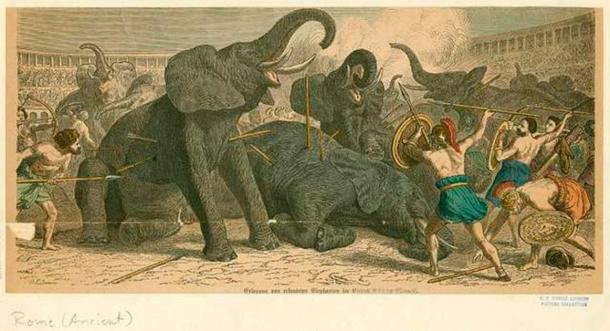

Drawing of the gladiator games called venationes held inside the Roman Colosseum, made in the 17th century. (Jan Collaert/CC0)

As Rome transitioned from a Republic to an Empire these games grew even more popular due to the fact it was more important than ever for Roman leaders to look powerful. Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, was a major fan of the venationes. During his reign, he boasted of holding 26 hunts, during which over 3500 African beats were killed. In one hunt alone, held at the Circus Flaminius, 36 Egyptian crocodiles were put to death. The crowd loved it.

- Elephants, Peacocks, and Horses: The Amazing Animals of Alexander the Great

- Humans A Major Factor In the Extinction of Giant Cave Bears

The Animals of the Gladiator Games

When we imagine the animal hunts held at the Colosseum a handful of creatures come to mind. Mainly exotic beats like lions, tigers, and elephants. In reality, the choice of animals was much broader, and wild animals from all over the Roman Empire were brought in to die in the games.

As we said earlier, holding games was all about bragging rights. The more animals an emperor could bring in, the more impressive it was. For example, Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD) received much praise for holding games that featured “all the animals of the whole earth”. This was of course an exaggeration, but only just.

The games Antoninus held featured lions, rhinos, crocodiles, hippos, cheetahs, monkeys, and elephants which had been brought in from Africa. From Asia, he shipped tigers, leopards, panthers, and cheetahs. He even went as far as to bring in bears that had been captured in the highlands of Scotland.

These bears were particularly impressive because Scotland, then known as Caledonia, wasn’t even part of the Empire. The bears had been captured in hit-and-run raiding expeditions held beyond Hadrian's Wall.

It wasn’t just vicious beasts and predators who met their ends during the games. Less fierce beasts were also common. For example, zebras and ostriches were used to pull chariots before being slaughtered and elephants were forced to perform tricks.

Featuring more docile animals in the games came at a risk, however. The Roman crowds may have been bloodthirsty, but it seems even they had their limits. In 55 BC, Pompey held a massive venatio to celebrate the opening of his own theater. He amazed the crowd with the sight of 500 lions being hunted.

Elephants slaughtered for entertainment. (Public Domain)

His grand finale didn’t go to plan though. The games were to end with elephants being put to the sword. But Plutarch recorded how when the elephants were killed, the crowd did not cheer, feeling only, ‘compassion and a kind of feeling that that huge beast has a fellowship with the human race.’ Another venatio went similarly off the rails when the organizers arranged for giraffes to be culled at the games. The poor beasts were so docile that the crowd didn’t enjoy seeing them killed.

Unsurprisingly, using these exotic beasts came at a great cost and was a logistical nightmare. In reality, less exotic animals like wild boar, bulls, deer, stags, dogs, and goats were also slaughtered as part of the games to keep costs down. It’s just that ancient sources were far more impressed with and spent much more time describing the more fabulous beasts.

Numbers

The actual number of animals killed at these games is simply staggering. Augustus may have boasted of having 3500 wild beasts put to death during his reign, but that number pales in comparison to later Roman rulers.

We have no concrete numbers and have to take some ancient claims with a pinch of salt, but if even remotely accurate the numbers are eye-watering (and stomach-churning). The ancient historian Suetonius recorded that over 5000 animals were killed in a single day when the Colosseum was first opened. While this is largely believed to be an exaggeration, the claim made by Cassius Dio that over 9000 animals were killed during the Colosseum’s first 100 days is seen as more reliable and barely less awful.

Another prime example is the 123-day-long games held by Emperor Trajan in 108 AD. It was recorded that during these games at least 11000 animals were slaughtered.

The number of animals butchered at the games was so high that some animals disappeared from their natural habitats entirely and were brought to the verge of extinction. Thanks to the Romans, hippos could no longer be found swimming the Nile and no lions roamed Mesopotamia. North African elephants, European wild horses, great auks (a species of flightless bird), and Eurasian lynxes all disappeared.

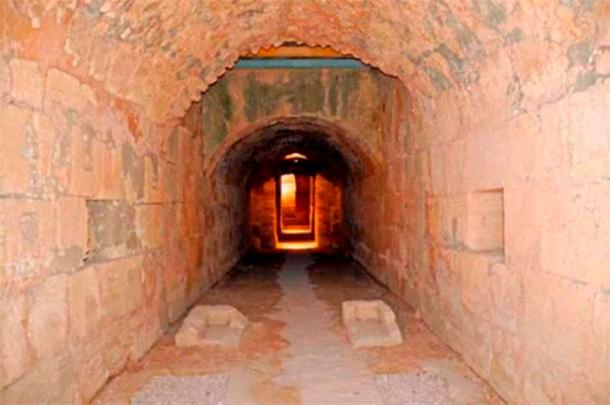

- Ancient Roman Tunnel from Gladiator Training School to Colosseum set to be Revived

- War Pigs: A Flaming History of Nature’s Cutest Creations in Battle

Logistics: Sourcing and Transporting the Animals

So where did all these animals come from and how did the Romans get them to the games? Well, it was big business. Since the whole point of using exotic animals in the games was to show off, the Romans had little interest in breeding the animals within the empire. Animals that had been caught in the wild were seen as more dangerous, exciting, and therefore, valuable.

As such, capturing and transporting these wild beats became incredibly lucrative. Today we have access to several ancient texts which describe in detail how some of these animals were captured. Pliny, for example, recorded how African hunters sourced live elephants.

Men on horses would chase the poor elephants into pits. Once trapped, the elephants would be left with no food or water until they became weak enough to easily transport. Then once they got to Rome, the animals would be fed and watered until they regained their physical strength, ready for the slaughter.

Another historian, Oppian, wrote about how the bears of Armenia were captured for the games. After local hunters had found bear dens using dogs, they drove the animals out using trumpets and cymbals. The distressed and disoriented bears were then chased into hidden nets. As the bears thrashed, the hunters tied their limbs to wooden planks. The bears were then loaded into a wooden cage ready for transport.

According to Oppian, a similar method was used to capture lions in Libya. Men on horses would chase them into a man-made pit. Once the lion was trapped, a cage baited with meat would be lowered into the pit. The lion would jump in the cage and then be lifted out of the pit and sent on its way to Rome.

We have less detail on how the animals were actually transported to the games. It seems that the animals were usually transported to the arena in cages or crates that were placed on carts or wagons.

Transportation would have been no easy task. The animals were difficult to control and posed a danger to their handlers and those around them. Trainers and handlers had to use various methods to keep the animals calm during transportation, such as feeding them, providing water, and using sedatives. It would have been a balancing act of keeping the animals weak enough to safely transport without accidentally killing them outright.

Besides the money involved, sourcing and transporting the beasts was lucrative in another way, reputation. It was not uncommon for Roman politicians to pressure their governor friends to send them animals to be used in the games. Doing so was an effective way to win the favor of important politicians and show one’s loyalty to the empire. Failing to send animals from your province was likely to do the opposite.

Centuries ago, this tunnel was used to transport gladiators or animals to the arena floor through an ancient ‘elevator’ located on the floor stones. (Dennis Jarvis / CC BY SA 2.0)

How Were They Kept?

Unsurprisingly, making sure the animals were comfortable wasn’t a major concern for those who held the games. The animals were usually held in cages that were far too small and were made of wood or metal. The main concern was keeping the animals contained and alive, ready for their use in the games.

The animals which were predators were usually given a diet of raw meat. But not too much. To ensure the animals performed as desired, it was common to keep them hungry so that they would attack when provoked.

The Romans had gone to great lengths to get the beasts to the games, so some measures were taken to keep the animals healthy. They were usually looked after by trained handlers and veterinarians. The handlers were responsible for feeding and watering the animals, cleaning their cages, and monitoring their behavior to ensure they were not becoming sick or injured.

Some of these trainers, known as venatores, were also the ones who would eventually kill the animals. It was the venatores’ job to train the wild animals to fight in the arena. This was easier said than done.

Many of the animals were forced to act against their natural instincts. A coin from the third century shows an elephant fighting a bull, not a common occurrence in nature. Similarly, a popular event during the Colosseum’s opening games forced crane birds to fight each other to the death. Other unnatural battles included bears vs snakes, lions vs crocodiles, and other strange mixes.

In all these cases the animals had to be trained to attack each other, rather than just ignore each other, or even run away. Sometimes, the only choice was to chain them together until they fought each other out of sheer annoyance.

Two Venatores (those who made a career out of fighting in arena animal hunts) fighting a tiger. Floor mosaic in Great Palace of Constantinople (Istanbul), 5th century. (Public Domain)

Battles with the Animals

The real job of these venatores though was to butcher the animals. The venatores usually had a similar background to the gladiators who featured in the main events; prisoners of war, slaves, or poor peasants looking to pay off crippling debts.

Just like the gladiators, the venatores were trained in special schools, the most famous of which was founded by Emperor Domitian and was known as Ludus Matutinus. It was where the venatores were taught how to train and then kill their exotic beats.

Ludus Matutinus on a map of ancient Rome around 300 AD (fr:User:ColdEel & edited by nl:Gebruiker:Joris1919/CC BY-SA 3.0)

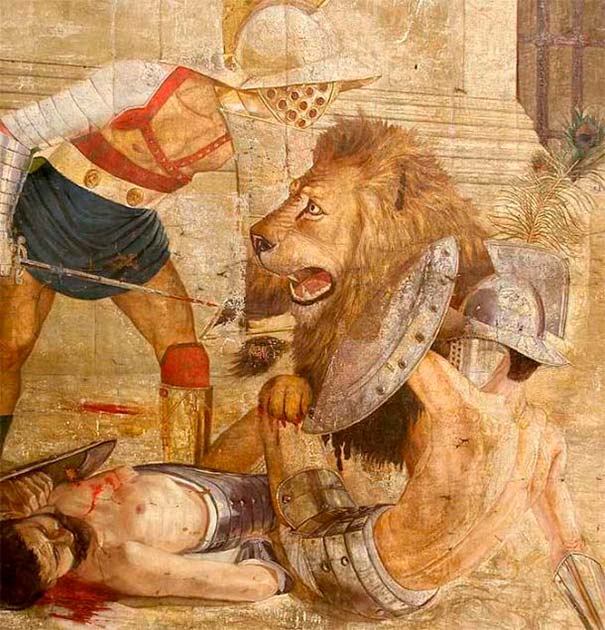

The staged hunts were held on artificial stage sets that were designed to represent the natural habitat of the featured beasts. Depending on the event, the venatores would take on animals like bears, lions, and cheetahs using arrows and spears. In the most dangerous events, they would get up close and personal with the animals with nothing more than a light tunic and a short spear for defense.

Not all venatores were lowborn, however. Some were rich nobles looking to show off and prove their courage (like some big game hunters today). Emperor Commodus was obsessed with the games and often took part himself, killing an untold number of wild animals. In all likelihood, these rich venatores weren’t fighting fairly. It’s likely that the animals were tied down or otherwise put at a disadvantage so that the elites could show off without risk of personal injury. It’s much less fun if your prey can fight back after all.

Below the venatores came the bestiarii. It was their job to use tools such as whips and lassos to bait the animals into a frenzy and make them attack. They also oversaw the damnatio ad bestias.

The damantio ad bestia was the event during which prisoners who had been sentenced to death were thrown to the animals. The event had two versions, both incredibly disturbing.

Prisoners thrown in arena to be devoured by wild bears in a Roman amphitheater during Gladiator games. (Massimo Todaro/Adobe Stock)

In the first, prisoners were given either a sword or spear and given no choice but to fight for survival. It was expected that with no training and such basic equipment, the prisoners would quickly fall to the beasts. In the unlikely occurrence they managed to survive, a second beast would be released to finish them off.

The second version was reserved for the lowest of the low, like political enemies or persecuted groups. These people were not expected to fight at all. They were simply thrown to the animals naked to be torn to shreds. These events were usually held as a kind of warm-up act between the morning's beast hunts and the afternoon’s gladiator battles.

A Murmillo gladiator fights a big maned Barbary lion in the Colosseum in Rome during a condemnation of beasts (Public Domain)

Conclusion

There is perhaps no better example of Roman blood lust than the use of exotic animals in gladiator games. Forcing men to fight each other to the death for entertainment was disturbing enough, but adding animals to the mix arguably took it to another level.

These animals were dragged from their habitats, transported in harsh conditions, and kept in cramped cages, subjected to stress and abuse for the sake of human amusement. Fortunately, modern times have brought about increased awareness and respect for animal rights, and laws and regulations now exist to protect animals from such practices.

But we still have a long way to go. Before we judge the Romans too harshly, we have to remember that dog fighting, cock fighting, and bullfighting are still a thing. In fact, thousands of wealthy Westerners travel to Africa every year to hunt big game, for leisure. That’s not to mention the continued existence of poaching, the ongoing trade in endangered animals and their body parts, or the countless species that become extinct every year.

Top image: A gladiator fights a lion at the Gladiator Games in ancient Rome. Source: (DigitalGenetics/Adobe Stock)

References

Aldrete. G. 2020. Flavian Amphitheater: Battle Arena for Man versus Animals Fights. Available at: https://www.wondriumdaily.com/flavian-amphitheater-battle-arena-for-man-versus-animals-fights/

Aptowica. C. 2022. Could You Stomach the Horrors of 'Halftime' in Ancient Rome? Available at: https://www.livescience.com/53615-horrors-of-the-colosseum.html

Cartwright. M. 2013. Roman Games, Chariot Races & Spectacle. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/635/roman-games-chariot-races--spectacle/

Wazer. C. 2023. The Exotic Animal Traffickers of Ancient Rome. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/03/exotic-animals-ancient-rome/475704/