Cemetery Reveals Medieval Equivalent of Social Benefits System

Archaeologists from several universities in England teamed up to analyze the skeletal remains of more than 400 individuals who were buried in a medieval cemetery that belonged to St. John the Evangelist Hospital in Cambridge. Their comprehensive study of the bones of these unfortunate souls has provided detailed information about the users of what was, in essence, a medieval social benefit system which functioned over hundreds of years.

Constructed and opened for business by its church in 1195, St. John the Evangelist Hospital was tasked with the mission of providing housing and medical services to the “poor and infirm.” The deceased interred at the cemetery came from a diverse set of backgrounds, united only by their eternal connection to the ruins of the 800-year-old charitable institution.

- Face of ‘Ordinary Poor’ Man from Medieval Cambridge Graveyard Revealed

- Why the Christian Idea of Hell no Longer Persuades People to Care for the Poor

The hospital or shelter itself was relatively small in size, only housing about a dozen or so inmates (plus several clerics and lay servants) at any one time. But the institution remained open for a long time, until it was finally replaced by medical and residential facilities built at St. John’s College in 1511.

In total more than 400 people lived, died and were buried at St. John the Evangelist, and the collective skeletal remains of all these individuals tell a fascinating story about what life was really like for the destitute who used the services of this medieval benefit system which existed during the Late Middle Ages.

Members of the Cambridge Archaeological Unit at work on the excavation of the Hospital of St. John the Evangelist in 2010. (Cambridge Archaeological Unit)

A Medieval Benefit System: Sheltering the Needy in Needy Times

Up to now, the lives of the people buried at this medieval cemetery have remained shrouded in mystery. “Medieval hospitals were founded to provide charity, but poverty and infirmity were broad and socially determined categories and little is known about the residents of these institutions and the pathways that led them there,” the British archaeologists wrote in a new article appearing in the journal Antiquity which discussed the remains of beneficiaries of the medieval benefit system.

Setting out to address this lack of detailed knowledge, the archaeologists pursued a multi-level strategy to learn as much as they could from the cornucopia of skeletal remains, which were first excavated in 2010. Combining physical examination of the bones with more exotic isotopic and genetic studies, they were able to construct a surprisingly comprehensive reconstruction of the physical and social conditions of the people buried in the hospital’s cemetery.

Their findings “highlight the value of collective osteobiography [a term describing the historical study of human bones] when reconstructing the social landscapes of the past,” the study authors declared.

One thing the archaeologists already knew going in is that demand for beds at St. John the Evangelist Hospital and the services provided by this medieval benefit system would have been intense. “Like all medieval towns, Cambridge was a sea of need,” archaeologist and study author John Robb from the University of Cambridge explained. “A few of the luckier poor people got bed and board in the hospital for life. Selection criteria would have been a mix of material want, local politics, and spiritual merit.”

The image shows the human remains unearthed at the former Hospital of St. John the Evangelist in Cambridge, as part of a study on medieval cancer rates. (Cambridge Archaeological Unit / St John's College)

Bones Reveal the Truth About Destitute Users of Medieval Benefit System

As a result of their research, the study authors have learned quite a bit more about which sick and destitute people would have gained admittance to the hospital. This information provides details about what kind of people would have been allowed to live there indefinitely or until their circumstances improved (in medieval England both poverty rates and rates of chronic illness and infirmity were high).

- More Than 1,000 Ancient Skeletons Found Beneath Cambridge University

- Medieval Cancer Rates Were Shockingly High, New Study Shows

Even before beginning this research, the archaeologists did have some idea about the categories of people ineligible for admittance to the facilities of this medieval benefits system. “We know that lepers, pregnant women and the insane were prohibited, while piety was a must,” Robb said.

There was a reciprocal obligation for those who were let in. Inmates were required to pray for the souls of those who funded the hospital, as a way to speed the latter’s post-life entrance into heaven. “A [medieval] hospital was a prayer factory,” Robb quipped.

In comparison to the bodies of medieval Cambridge residents buried elsewhere, the inmates entombed at the St. John the Evangelist cemetery were an inch shorter in height on average. Their bones showed signs consistent with malnutrition and disease in childhood, which could explain the stunted growth.

But the skeletons also demonstrated a lower incidence of body trauma, in comparison to poor people found in other medieval cemeteries. This suggests they were protected from physical attack and harm while under the Hospital staff’s care.

Some of the bodies interred at the St. John the Evangelist cemetery were children. These children were unusually small, lagging about five years’ worth of height behind for their ages on average. “Hospital children were probably orphans,” Robb theorized.

In addition to poor residents, the archaeologists were also able to identify a few skeletons they believe belonged to scholars from the University of Cambridge. Based on the good condition of their bones, it was clear these individuals consumed nutritious foods and didn’t do much manual labor (yet they were still allowed to live on hospital grounds).

Interestingly, the researchers discovered that eight hospital residents had apparently been in good physical condition when younger, but had declined in health as the quality of their diets had dropped dramatically in older age. The researchers speculate that these could be examples of the “shame-faced poor,” a medieval term for those who were once prosperous but had slipped into destitution later in life, perhaps because they were no longer able to work and didn’t have families to care for them.

“Theological doctrines encouraged aid for the shame-faced poor, who threatened the moral order by showing that you could live virtuously and prosperously but still fall victim to twists of fortune,” Robb explained.

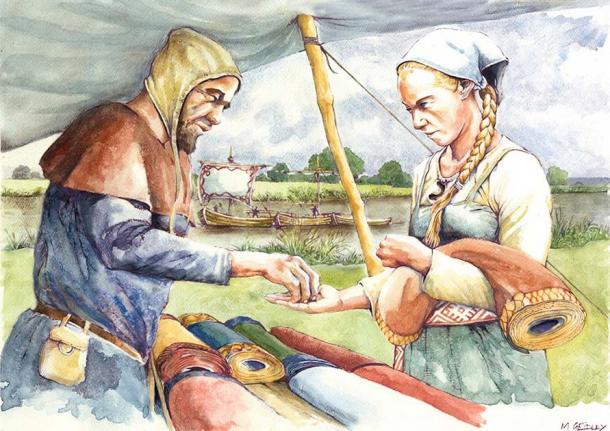

Illustration based on osteobiography generated through analyses of remains of Christiana born between 1256 and 1277 excavated at cemetery of Cambridge hospital which offered a medieval benefit system. (Mark Gridley / After the Plague)

Biographies from the Bones: Life in Medieval Cambridge Revealed

Taken altogether, the results of this analysis show that medieval hospitals took responsibility for the care of people from different backgrounds, primarily those who’d reached desperate stages of their lives by different means.

- HALF of the Men Found in Medieval Paupers’ Cemetery Had Broken Bones

- Skeletal Trauma Reveals Class Inequality in Medieval Cambridge

“They chose to help a range of people. This not only fulfilled their statutory mission but also provided cases to appeal to a range of donors and their emotions: pity aroused by poor and sick orphans, the spiritual benefit to benefactors of supporting pious scholars, reassurance that there was restorative help when prosperous, upstanding individuals, similar to the donor, suffered misfortune,” state the authors in their Antiquity article.

Timed to coincide with the release of this new study, the British archaeologists are launching a website that will provide extended osteobiographies that reveal the life details of 16 medieval residents of Cambridge. This includes a few who were buried at the St. John the Evangelist Hospital cemetery and others who were buried in different locations.

Top image: Illustration based on osteobiography generated through analyses of remains excavated at cemetery of Cambridge hospital which offered what was, in essence, a medieval social benefit system Source: Mark Gridley / After the Plague

By Nathan Falde

Comments

"Inmates were required to pray for the souls of those who funded the hospital, as a way to speed the latter’s post-life entrance into heaven."

I have no doubt this was so. However, I genuinely doubt it actually works that way, always. If one was to become obscenely rich through ripping people off, for example, giving a fraction of the proceeds to a hospital charity may have made one seem philanthropic, but the love was not of people, rather of Mammon and self, which is still sinful.

Heavenly judgement is not as easily fooled as some people are. This applies today, as it did in Medieval times.