Why the Dark Ages Weren't Really All That Dark

For hundreds of years, a period often referred to as ‘the Dark Ages’, covering the 5th to the 10th centuries, was looked down upon by historians, especially during the Renaissance and Enlightenment eras. It was seen as a dormant period during which art and intellectualism languished. Thankfully more modern historians have taken a more balanced view. Far from a dormant period, it stands as a dynamic era defined by human resilience and innovation. From the meticulous manuscripts in monasteries to the towering cathedrals, the Dark Ages unveiled a nuanced chapter in history. In many ways, the Dark Ages weren’t so dark, and common people lived better lives than their counterparts would have during the so-revered classical period.

Redefining the Dark Ages: The Good Old Days

Ever had an elderly relative complain that things aren’t as good today as they were in the “good old days”? Well, that’s pretty much where the whole myth surrounding the Dark Ages began. People complaining.

Romulus Augustus resigns the Crown before Odoacer. (Public Domain)

In 476 AD the Western Roman Empire officially ended when the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer. From this point onwards what had once been the glorious Roman Empire was divided up by numerous Germanic peoples who, understandably, ignored old Roman traditions and brought in their own.

Those educated enough to be writing at the time, men like St. Jerome and St. Patrick in the fifth century, Gregory of Tours in the sixth, and Bede in the eighth tended to have a strong Roman bias and began writing how things under the Germanic tribes weren’t as good as under the Romans. To an extent, they had a point.

In some ways, these Germanic tribes simply weren’t as advanced. For example, innovations like Roman concrete and many other engineering marvels were lost and the literacy rate plummeted. However, these drawbacks were heavily exaggerated by later scholars.

The actual idea of the “Dark Ages” comes from a mid-14th century Italian scholar, Petrarch, who divided all of history into two periods- the Classical and the Dark Ages (which he believed he lived in). To Petrarch, the Classical period was a time when the Greeks and Romans had showered the world with intellectual and philosophical achievements. The Dark Ages on the other hand were a period of stagnation where nothing could live up to the ‘Good Old Days.” It was a case of rose-tinted glasses.

Petrarch conceived the idea of a European "Dark Age". (Public Domain)

Petrarch wasn’t alone either. The 9th-century Carolingian writer Walahfrid Strabo had made similar comments centuries earlier, bemoaning he hadn’t gotten to live in the more enlightened times of the Carolingian Renaissance (which we’ll come to later) under Charlemagne.

Petrarch’s idea of a Dark Age took root and inspired later historians and writers. When the Renaissance came along between the 15th and 17th centuries the humanists lapped up Petrarch’s idea of a barbaric medieval past. It played right into their belief that they were reviving long-lost classical culture.

The Enlightenment Plays Along

The reputation of the Dark Ages only got worse during the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries. Humanists had a problem with the Dark Ages because they saw it as a time when Latin language, literature, and culture had languished. The Protestants on the other hand saw it as a time during which the Catholic Church had grown fat and corrupt. It’s these criticisms that led the scholars of the Enlightenment to declare war on the Dark Ages.

The Enlightenment was all about the pursuit of knowledge and happiness and placed great emphasis on qualities such as reason, progress, light, and freedom. Its scholars believed the Dark Ages epitomized the exact opposite. While the Dark Ages had largely been ruled over by Papal corruption, the Ancient Greeks had given the world its first true democracy.

Weimar's Courtyard of the Muses by Theobald von Oer, a tribute to The Enlightenment and the Weimar Classicism depicting German poets Schiller, Wieland, Herder, and Goethe. (Public Domain)

This caused scholars like the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann to argue Greek classical art was superior because it hadn’t been created under tyrannical rule. This led to the creation of a new art form, neoclassicism, designed to emphasize the superiority of everything classical over Medieval.

The only problem with this train of thought is it was wrong. The Dark Ages were arguably simply different, not worse than the classical period. By listening to medieval scholars bemoaning the loss of the “good old days” Renaissance and Enlightenment historians overlooked the many bright spots of the Dark Ages.

The Carolingian Renaissance Would Like a Word

For a start, this way of thinking completely ignores the Carolingian Renaissance. In 768 AD Pepin the Short, a Frankish king, died and his two sons inherited his entire kingdom. One of them, Carloman, died a few years after his father while the other survived.

The survivor’s name was Karl but after taking complete control he became known as the legendary King Charlemagne, also known as Charles the Great. Through at least 50 massive military campaigns he took anyone who stood in his way- the Muslim rulers of Spain, the Bavarians, the Saxons in Germany, and Italy’s Lombards. As he did so the Frankish Empire grew into a medieval powerhouse. Where Charlemagne went, he spread his Catholic faith with him and in 800 AD Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne “emperor of the Romans.”

Charlemagne became known as the “Holy Roman Emperor,” a nod to how many believed his rule would take Europe back to the glory days of the Roman Empire. The king lived up to his new title, creating a centralized state whose buildings were inspired by Roman architecture.

Charlemagne also pushed educational reform and worked hard to ensure the preservation of ancient Latin texts. It was also during this time that a standard handwriting script, Carolingian minuscule, was invented.

Going beyond nice penmanship, it standardized things like punctuation, spacing, and the use of upper and lower cases. This in turn revolutionized literacy and reading and made it that much easier to produce books and other texts.

Unfortunately, the Carolingian Renaissance was a bit of a flash in the pan. Charlemagne died in 814 AD and his dynasty didn’t survive much longer after him. Still, its contributions to literature, art, and education provided the foundations for techniques used during the Renaissance and Enlightenment centuries later.

The Rise of the Catholic Church

During the Enlightenment much was made of the corrupting power of the Catholic Church during the Dark Ages. The Dark Ages were both a barbaric time and a time when the Catholic Church ruled with an iron fist. But the truth is a little more nuanced.

Ignoring Charlemagne’s little renaissance in the early years of the Dark Ages it is somewhat true that Europe lacked a unifying power like the Roman Empire to keep everything in check. But that was quickly fixed by the rise of the Catholic Church.

Miniature of Gregory the Great writing, from a 12th-century copy of his Dialogues (British Library/CC0)

The spread of Catholicism meant many of medieval Europe’s kings and queens derived most of their power from their relationship with the church. As the papacy grew in strength, beginning with Gregory the Great (590-604) monarchs couldn’t monopolize power like they had during the Roman Empire. No man was bigger than God (or the Pope). While it’s true that the rot eventually set in and the Popes became mind-bogglingly corrupt, it wasn’t all bad.

Religion and Education

The power the Catholic Church wielded during this period led Protestant Reformers and Enlightenment thinkers to call it dark. In particular, they wrote that during the Dark Ages, the popes and their clergy had done their best to repress intellectual thinking and scientific advancement.

However, this way of thinking ignores the rise of monasticism and how the early Christian monasteries actively encouraged both literacy and learning. Many medieval monks adored the arts and were artists themselves, they didn’t just sit around praying all day.

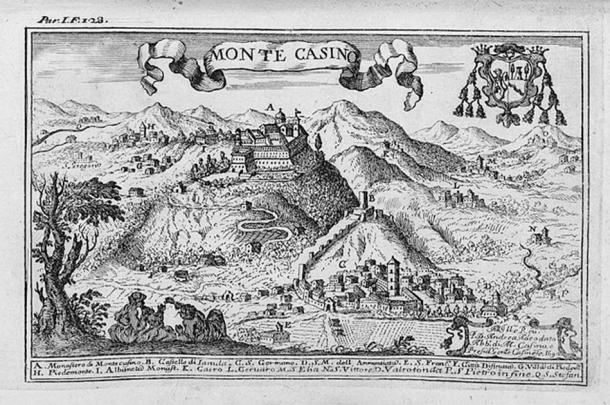

The monastery depicted in Giovan Battista Pacichelli's 1703 Il regno di Napoli in prospettiva (Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla from Sevilla, España/CC BY 2.0)

Take for example Benedict of Nursia (480-543), founder of the great monastery of Montecassin. His Benedictine Rule, as it came to be known, provided a comprehensive guide for communal life in a monastery, emphasizing prayer, work, and study. It quickly spread across Europe and inspired many Western monasteries.

Benedict believed that “Idleness is the enemy of the soul” and the monks who followed his rule often became great scholars. They believed that monks should do manual as well as intellectual and spiritual labor. Which sounds pretty enlightened for the Dark Ages.

Advances in Science and Mathematics

There’s long been the idea that the Catholic Church suppressed the sciences during the Dark Ages, especially when it came to medical science and the study of things like dissections and autopsies. This is true to an extent- scientists certainly had to be careful to make sure anything they discovered didn’t contradict Catholic teachings or threaten the church’s rule.

However, the idea that there was basically no scientific advancement during the period is a gross exaggeration. There were scientific advancements, they just came a little slower than during the classical period.

This way of thinking also completely ignores the Islamic World, which was most definitely not suffering a dark period. During the Dark Ages, the Islamic world made leaps and bounds in the realms of both math and sciences, building on the work of ancient Greek texts that had been translated into Arabic.

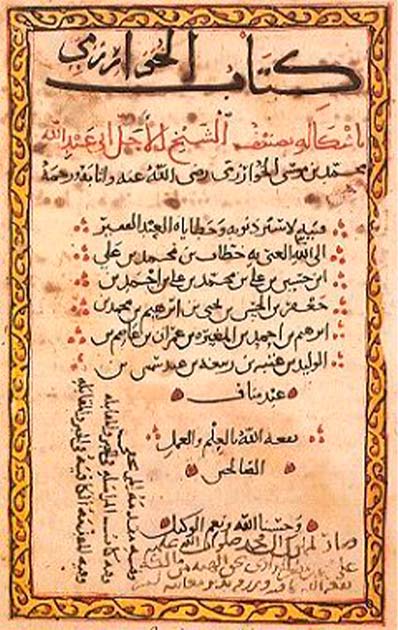

A page from al-Khwārizmī's Algebra book: The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing. (Public Domain)

The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, written by al-Khwarizmi (a Persian), might be a bit of a mouthful but it revolutionized mathematics and gave Europe algebra. Not only did it introduce the first systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations, but it also gave us the decimal points that we still use today. The word algorithm even comes from the Latinized version of the author’s name.

Basically, when Renaissance and Enlightenment writers bemoaned the Dark Ages, they were completely ignoring many of the advancements made by Islamic thinkers during the period. White Europeans marginalizing the achievements of another ethnic group? It certainly wasn’t the first, or last time.

The Rule of Law

The romanticization of Greek and Roman civilization also tended to ignore the many, many downsides of being alive during that time. Like the fact that for most people (like slaves) it was really, really unpleasant.

The early Middle Ages was a period during which fairer systems of law began to prevail. These law systems were far from perfect for sure, but they tended to do a better job at protecting “normal” people. Traveling merchants were protected by Lex Mercatoria (Law Merchant) which featured the idea of arbitration and was designed to protect merchants and encourage good practices between traders.

Anglo-Saxon Law during the early Middle Ages focused on keeping the peace and protecting people. While it eventually became harsher and more draconian, for a long time it was relatively flexible and fair.

While later scholars looked down on the many changes made by the Germanic peoples they brought in Early Germanic Law. These laws ensured everyone the right to be tried by their own people and were designed to protect people from the dangers of ignorance and cultural prejudice. Many of the laws founded during the Dark Ages form the basis for laws still in action in much of Europe today.

- Forged Medieval Charters: How To Rewrite History In The Middle Ages

- Caught Red-Handed! Law and Order in Medieval England

Weather and Agriculture- It Literally Wasn’t Very Dark

It’s not just the new laws that made the Dark Ages a “not so bad” time to be alive. The weather was also surprisingly good. The period’s name tends to conjure up images of dark skies, rain, and snow but in reality, the Dark Ages was a period of warming for the north Atlantic region.

By the High Middle Ages (around 1100 AD) Europe was well into a period now called the Medieval Warm Period. It was particularly beneficial for the Vikings who, thanks to melting ice, could finally colonize Greenland and its neighbors.

For the rest of Europe, it meant an agricultural boom. The improved weather, alongside improved agricultural knowledge, meant there was plenty of food. In fact, there was such a surplus of food that livestock could be fed on grains, not grass which upped production.

At the same time feudalism (despite its many downsides) encouraged efficient land management and in many areas introduced the idea of crop rotation. It was also built on reciprocal relationships of obligation. Lords were expected to protect their vassals, and in return, vassals provided military service.

This interdependence could foster a sense of security within the feudal structure. Meaning contrary to popular belief the Dark Ages weren’t such a bad time to be a peasant and were much better than during the Roman Empire.

Peasants working the fields in the Middle Ages. (Gilles de Rome/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Conclusion

In revisiting the often-misunderstood epoch labeled the Dark Ages, it becomes evident that beneath the conventional narrative of stagnation lay a tapestry of vibrant achievements. Sure, most people were certainly worse off than today but, in many ways, they didn’t have things so bad.

Art and literature still thrived, science wasn’t as stagnant as once believed, and the lower classes in particular were much better off than they had been during the classical period. There is an important lesson to be learned when examining the Dark Ages, be wary of rose-tinted glasses and the allure of the good old days. It’s easy to look around at the state of the world compared to the past and point out all the things that are wrong with it. Someone should have told Petrarch that the grass isn’t always greener on the other side.

Top image: AI Panoramic view of the castle during the Dark Ages. Source: DIGITALSHAPE/Adobe Stock

Comments

Anyone who regards feudalism as good should be pleased to know it is returning now, along with the myth of 'mutual obligation'. This means that those at the bottom are obliged to believe those at the top care, while those at the top are obliged to occasionally pretend they care.