Sati Widow-Burning: A Dark Chapter in Indian History

Sati, the practice of a widow self-immolating on her husband's funeral pyre, remains one of the most controversial and emotive issues in South Asian culture. While some view it as a sacred funerary ritual, others see it as a barbaric act of violence against women. While the practice has been banned repeatedly over the centuries, it has never disappeared completely. Nevertheless, before we condemn something, it is important to understand it.

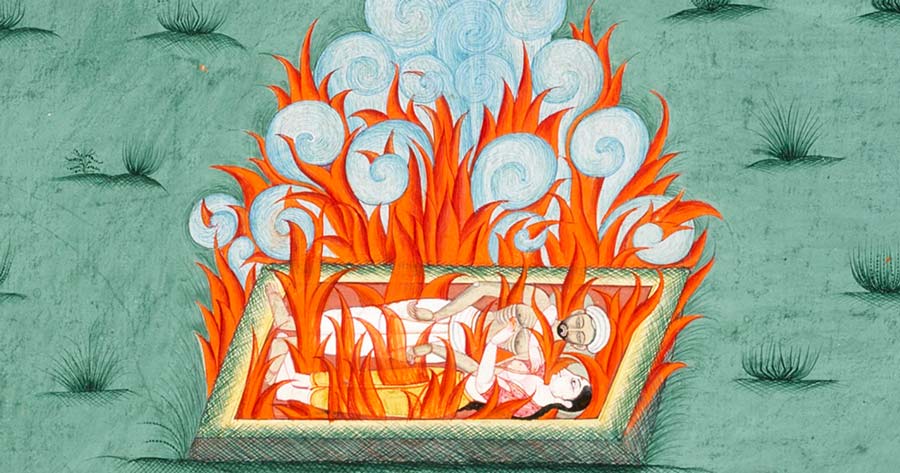

Young Hindu girl throwing herself on the funeral pyre of her beloved, the Sati practice, to illustrate a poem by Naw'i Khabushani, illustrated by Muhammad `Ali Naqqash Mashhadi circa 1657. (Public domain)

Understanding the Meaning of Sati Widow Immolation

There are several distinct types of Sati. Originally, Sati referred to a woman who performed the act of self-immolation (setting oneself on fire) after the death of her husband. The word Sati comes from the Sanskrit word sasti, which translates as “she is pure or true.”

In Hindu mythology, Sati is a goddess who is married to Lord Shiva. In the myths, Sati’s father never approved of the union and hated Shiva. Sati, in an act of rebellion, burned herself to protest her father’s disdain for her husband. Legend has it that as Sati was burning, she prayed to be reborn as Shiva’s wife. Her prayer was granted and Sati was reborn as Parvati.

- Nine Weird and Wonderful Facts about Death and Funeral Practices

- Manikarnika Ghat and the Role of Cremation in Traditional Indian Funerary Rites

Early Hindu’s looked to this myth as justification for the practice of Sati, despite the fact that Sati wasn’t a widow. Historically, there were two main types of Sati; voluntary and forced. In ancient Hindu customs, Sati represented the closure of a marriage. By immolating herself, the wife was following her husband to the next life in an act of ultimate devotion and loyalty.

Unsurprisingly, not every wife wished to jump on the funeral pyre with her husband. Over time, women who refused to do so willingly were forced to die alongside their husbands. While people used religious excuses to carry out forced Sati (a.k.a. murder) the truth was much more practical. Traditionally, Hindu widows had no role to play in society and as such were seen as a burden, the thinking being that if a woman had no children who could / would support her.

Shiva carrying Sati’s corpse from the 19th century Kalighat paintings. (The Bodleian Library / CC BY 4.0)

Different Types of Sati Execution in Hindu Culture

There are various accounts that tell us how Sati was carried out over time. Most of them involve immolation. Normally, they depict women sitting on their husbands’ funeral pyre or lying down next to their bodies. In some accounts, the pyre is lit first and then the widow walks or jumps into the flames. In other accounts, the widow sits on the pyre and then lights it herself. The practice could also differ from region to region.

The 17th-century traveler Jean Baptiste Tavernier, for example, claimed that in some regions he saw people construct a small hut. The deceased husband and his widow were placed inside this hut and then it was set alight. In other regions, it was recorded that a pit was dug and then filled with the husband who was surrounded by flammable material. It was then set alight and the widow jumped into the roaring flames beneath her.

The hut and pit executions are perhaps the most disturbing. While technically voluntary, it has been noted it is much harder to clamber out of a burning pit, or escape a burning hut, than it is to jump off a burning pyre.

There were also some slightly less torturous methods. It was sometimes permissible for the widow to take poison or powerful drugs before she was burned. Sometimes the widow allowed herself to be bitten by a snake or used a sharp blade to open up her throat or wrist before jumping into the flames.

Gouache painting by Thanjavur depicting Sati, the practice of a widow self-immolating on her husband's funeral pyre. (Public domain)

Live Burials and Sati Exemptions

In most Hindu communities, burials are only carried out on those who died under the age of two, while anyone older is cremated. Notwithstanding, some sources claim that there was another type of Sati that featured live burials. A handful of European accounts from over the centuries describe a version of Sati in which the widow was buried alive with her dead husband. Tavernier wrote that the women of the Coast of Coromandel were buried with their husbands while people danced around them.

While it might be easy to dismiss European accounts as attempts at making certain Indian customs seem barbaric, the strongest evidence that live burials were carried out is the fact that the Sati Prevention Act of 1987 includes live burials within its definition of Sati.

This being mainly a Hindu custom, there was a caste element to the practice of Sati. There were also some religious exemptions. The first rule of Sati stated that any widow who was pregnant, having her period, or was caring for young children was banned from carrying out Sati. It was also believed that women who died via Sati died chaste. This gave them bonus karma and guaranteed them a better next life. So, there was some incentive.

On the other hand, women of the highest caste, Brahmin women, were usually exempt from Sati. The reasoning being that as the highest caste their karma was maxed out, meaning they couldn’t benefit from Sati and so didn’t have to practice it. Very convenient.

Handprints of wives of the Maharajas of Bikaner, all of whom who committed Sati on the pyres of their husbands, at Junagarh Fort in Bikaner, India. (Daniel Villafruela / CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Rise and Fall of Sati Customs in India

There is much debate as to when the practice of Sati as it is known today began. There is some evidence that the act of widow burning in the region dates back thousands of years. This being said, there are very few reliable sources that make mention of Sati in particular before 400 AD.

The Greek historian Aristobulus of Cassandreia is the earliest reliable source to mention Sati. After traveling to India with Alexander the Great in 327 BC, he wrote of the local custom of wives burning themselves with their husbands. Cicero, Nicolaus of Damascus, and Diodorus all also described similar instances of self-immolation.

Meanwhile, other Greeks who visited the region, like Megathenes, who visited in 300 BC, made no mention of the practice. It seems that, at least during the ancient period, an early form of Sati was being practiced in some parts of India. But the fact that not all Greek travelers made a note of it implies that the practice wasn’t widespread yet.

Most historians agree that Sati, as we know it today, was introduced into Indian society on a larger scale between 400 and 500 AD. It then slowly grew in prevalence until it peaked in around 1000 AD. According to one historian, Dehejia, Sati originally began amongst the Kshatriyas (warrior) aristocracy before spreading to other castes. Supposedly the Kshatriyas had a tendency of taking religious rules a little too literally, taking what was meant to be a symbolic practice and turned it into a practical one.

The practice then began to spread more and more quickly during the medieval period. It is believed this was due to the process of Sanskritization. This means that Sati was originally practiced by the higher castes, like the Kshatriyas, but that the lower castes began practicing it in the hopes of emulating their so-called “betters.”

Gouache painting of the act of Sati self-sacrifice. (Public domain)

Some historians also believe that over time Sati became conflated with another practice known as Jauhar. Jauhar was a form of self-sacrifice carried out by noble women during times of war as a way of preserving their honor when faced with defeat. Jauhar was traditionally practiced by the high-born Rajput caste, but like Sati it spread to the lower cates over time.

These historians believe that as Sati became more closely associated with Jauhar its meaning changed. It went from meaning “brave woman” to “good woman.” This meant it went from being something only high-caste warrior women should do to something all “good” women should do.

After peaking in around 1000 AD, the practice of Sati slowly started becoming less common again. This process sped up during the Mughal Empire between 1526 and 1857. Emperor Akbar (1556 to 1605) was said to have been very anti-Sati, expressing his respect for “widows who wished to be cremated with their deceased husbands,” but felt that immolating oneself was the wrong way to go about honoring a dead spouse.

He was also very anti-abuse in general and in 1582 outright banned forced Sati. Some historians have gone as far as to state that Akbar banned Sati outright, but no sources reflect this. It seems likely that the emperor heavily discouraged the practice but never went as far as an outright ban.

The first actual Sati ban came under Emperor Aurangzeb, who issued an order in 1663 stating “in all lands under Mughal control, never again should the officials allow a woman to be burnt.” European travelers who visited the empire in the years following the ban noted how Sati had become very rare, except in the case of families who were wealthy enough to bribe local officials into letting them carry it out.

The Mughal Emperor Akbar attempting to dissuade a young Hindu girl from committing sati self-immolation in a painting by Muhammad 'Ali Mashhadi circa 1657. (Public domain)

Colonial Powers in India and Their Attitude to Sati

The European powers who visited and took control of large swathes of India also did their best to ban the practice of Sati, the first being Alfonso de Albuquerque of Portugal. After conquering Goa in 1510, one of his very first acts was the banning of Sati. This lasted until 1555 when Brahmins convinced Francisco Barreto, who was fresh off of the boat, to rescind the ban. This led to major protests from local Christians and church authorities. The ban had been reinstated by 1560, with added penalties for those who encouraged Sati.

The Dutch and the French also banned Sati in their respective strongholds of Chinsurah and Pondichery. The Danes, who held the colonies of Tranquebar and Sermapore, eventually got around to banning Sati, but not until the 19th century.

Much has been made of the British impact on India over the years, and when it came to the practice of Sati, it’s a mixed bag. The first record of the British responding to Sati comes from 1680 when Streynsham Master, a colonial administrator, stepped in and stopped the burning of a Hindu widow.

Around the same time, other British officers had made attempts to curb or ban the practice in their provinces but were not backed by their masters at the East India Trading Company (not exactly famed for its morals). The company’s excuse was that it followed a policy of non-interference and had no right to interfere in Hindu religious affairs.

The first official British ban came in 1798, but only affected the city of Calcutta. Sati remained relatively widespread in the surrounding regions. From the beginning of the 19th century, churches in Britain and their members in India began campaigning against Sati. Missionaries in India, who were already busy trying to convert as many Indians as possible, began an education campaign aimed at discouraging the practice of Sati. These campaigns put the company under pressure to ban Sati outright.

Lord Hastings, the 18th-century Governor of India, shown as accepting bribes to allow a Sati ceremony to take place. (Public domain)

The 1829 Ban on Sati Practices in India

Throughout the early 19th century opposition to Sati amongst Christians and Hindu reformers began to grow. The problem was that not all Hindus took well to being told what to do by a bunch of foreigners. As a result, there was actually a rise in Sati cases, and between 1815 and 1818 Sati deaths doubled.

In 1828, Lord Willian Bentinck became Governor of India. Upon landing in Calcutta he made it abundantly clear that he felt banning Sati to be his moral duty. Despite the advice of some of his advisors who feared it would incite insurrection, on December 4, 1829, Regulation XVII was issued, officially declaring Sati as an illegal practice punishable in criminal courts.

- Bizarre, Brutal, Macabre and Downright Weird Ancient Death Rituals

- Jauhar - The History of Collective Self Immolation during War in India

Unsurprisingly, it faced stiff opposition. Many Indian Hindus saw it as an attack on their traditions and way of life. The British largely ignored these complaints, and the official stance was that no more Sati occurred after 1829. In reality, Sati wasn’t completely gone. The British didn’t control all of India and the practice continued in some princely states for a few more years. By 1852 most of the princely states had followed suit by banning Sati.

The biggest win came in 1846 when the state of Jaipur abolished Sati. It’s widely believed that this led the states within the region of Rajputana to follow Jaipur’s example. Within four months of the Jaipur ban, 11 of the 18 states within Rajputana had also banned Sati.

The final state to ban Sati in 1861 was Mewar, while the last legal case of Sati within a princely state came that same year. Queen Victoria attempted to put the final nail in the coffin of Sati practices later that year by issuing a general ban that affected the whole of India.

The widow of an Indian sacrificing herself at the stake of the bridegroom from an 1845 Illustrated Atlas. (Public domain)

Sati Practice in the Modern World

Over the following years, public opinion at large within India had turned against Sati and the number of Sati cases dwindled. Unfortunately, this isn’t to say Sati disappeared completely. In 1987, for example, an 18-year-old widow called Roop Kanwar was burned alive in Deorala village after her 24-year-old husband died. Several thousand people gathered to watch her burn, declaring her a devoted wife.

This event led to massive public outcry, forcing the Indian government to enact the Rajasthan Sati Prevention Ordinance on 1 October 1987. Later that same year the Commission of Sati (Prevention Act) was passed. This made it illegal to support, glorify or commit Sati. Forcing someone to commit Sati was now punishable by a death sentence or life imprisonment and glorifying it could land someone seven years in jail.

Sadly, time has proven that enforcement of the prevention act has been inconsistent at best. In the years following the re-banning of Sati, there have been several more high-profile cases. While some experts have attempted to label them as examples of mental illness and suicide, others aren't convinced.

The practice of Sati has been a topic of controversy for centuries in South Asian culture. While some see it as a sacred tradition and a symbol of a woman's devotion to her husband, others view it as a brutal manifestation of patriarchal oppression in India. While we must always be respectful of other people's cultures and customs, it is hard to see a place for practices like Sati in the modern world.

Top image: Detail of a painting depiction the Sati of Ramabai, the wife of Madhavrao Peshwa the ninth Peshwa of the Maratha Empire who reigned from 1761 to 1772. Source: Public domain

References

Agbo. N. 10 January 2020. “Sati: The Widow-Burning Culture in India” in The Guardian Life. Available at: https://guardian.ng/life/Sati-the-widow-burning-culture-in-india/

Doniger. W. 15 February 2023. “Suttee” in Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/suttee

Jain. R. 25 October 2022. “The History Behind Sati, a Banned Funeral Custom in India” in Culture Trip. Available at: https://theculturetrip.com/asia/india/articles/the-dark-history-behind-Sati-a-banned-funeral-custom-in-india/

Mishra. G. 7 August 2020. “Roop Kanwar: Last Known Case of Sati in India & Its Relevance Today” in Feminism in India. Available at: https://feminisminindia.com/2020/08/07/roop-kanwar-last-known-case-Sati-india-relevance-today/

Comments

As bad as British colonialism could be, it did at times attempt to do some good. In Australia, attitudes of early 19th century Aboriginal men towards women and girls could routinely be one of grievous domestic violence and even paedophilia. Calling it a patriarchy would be to severely understate the case. A wife could even be loaned out to another man, as if a mere minor chattel.

Sati was just one of India's sins. The caste system, which put the British class system to shame with regards to elite control was, and still is, another.

Modern history tends to focus controversially on the patriarchy or overlordship of the British colonists, ignoring that of the colonised, for political reasons, which is just a modern form of class control.

It is easy to think that the World is a much better place now, but that is purely a mirage created by media and academia in the service of sin.

Every win against sin is simply overshadowed by another loss. The end of Sati was a win, but there are events unfolding in India, as in Australia, that make the sacrifices of Sati look extremely tame.