Utopia, Euphoria: Greek Philosophers Searching For The Good Life

To the ancient Greeks, philosophy – literally the love of wisdom - as a therapy or treatment of bodily ailments implied a holistic, psychosomatic understanding of the human mind, body and soul. Conversely, some Greek doctors whose writings have come down under the collective label of ‘Hippocratics’ -in honor of a real Hippocrates, from the island of Cos, an older contemporary of Athenian Plato - philosophized for example, about whether or not disease in general or any one particular disease (such as epilepsy) could be considered to be of divine, super-human origin and causation. Could the ancient Greek philosophers assist modern man in attaining utopia, a good life within a good community, and did the irrational gods have any influence?

Bust of Plato (ca. 370 BC) Academia in Athens (Public Domain)

Plato’s Theaetetus

Plato, who possibly coined the original term ‘philosophia’, was big on medical metaphors – sometimes regarding philosophical nostrums as specifics for the betterment or cure of a sick body politic, at other times for a morally unhealthy individual soul. Much of Plato’s philosophy was to do with individual ethics, right and wrong, justice and injustice, where goodness, for him, required an ultra-high level of intellectual capacity. His most famous pupil Aristotle cast his intellectual net far wider, though he too wrote memorably on ethics, and especially on the ethics of friendship, but for him the social-political context of behavior mattered as much as did personal probity.

Plato presented his philosophy through the medium of invented dialogues, tried out first on his pupils at his Athens Academy of higher learning (founded in the 380s), later published on papyrus as finished works, many of which are also considered masterpieces of prose literature. They exemplify the so-called ‘Socratic’ Question-and-Answer method of enquiry, so named because Plato’s mentor Socrates (who never wrote a word) is featured in almost all of his dialogues as the principal interlocutor. It must be emphasized that these dialogues are not transcripts, but Platonic creations or fictions. The ‘Socrates’ character is very much Plato’s version of him. Plato lived to a very great age, and the dialogues were published over some three decades; the Theaetetus, named for one of Socrates’ two principal discussants, is thought to fall towards the end of that period.

Like most of the earliest, this dialogue focuses on a single definitional question, a matter of epistemology: What is knowledge? Theaetetus has three attempts at trying to define it, and none of them satisfies ‘Socrates’.

Like this Preview and want to read on? You can! JOIN US THERE ( with easy, instant access ) and see what you’re missing!! All Premium articles are available in full, with immediate access.

For the price of a cup of coffee, you get this and all the other great benefits at Ancient Origins Premium. And - each time you support AO Premium, you support independent thought and writing.

Taken from an Interview by Dr Richard Marranca with Dr Paul Cartledge, A.G. Leventis Senior Research Fellow, Clare College, University of Cambridge and author of Democracy: A Life

Dr Richard Marranca is an author, teacher and filmmaker. He has had a Fulbright to teach at the University of Munich, as well as seven National Endowments for the Humanities summer grants. His books are available online. Read more at: https://www.richardmarranca.com/

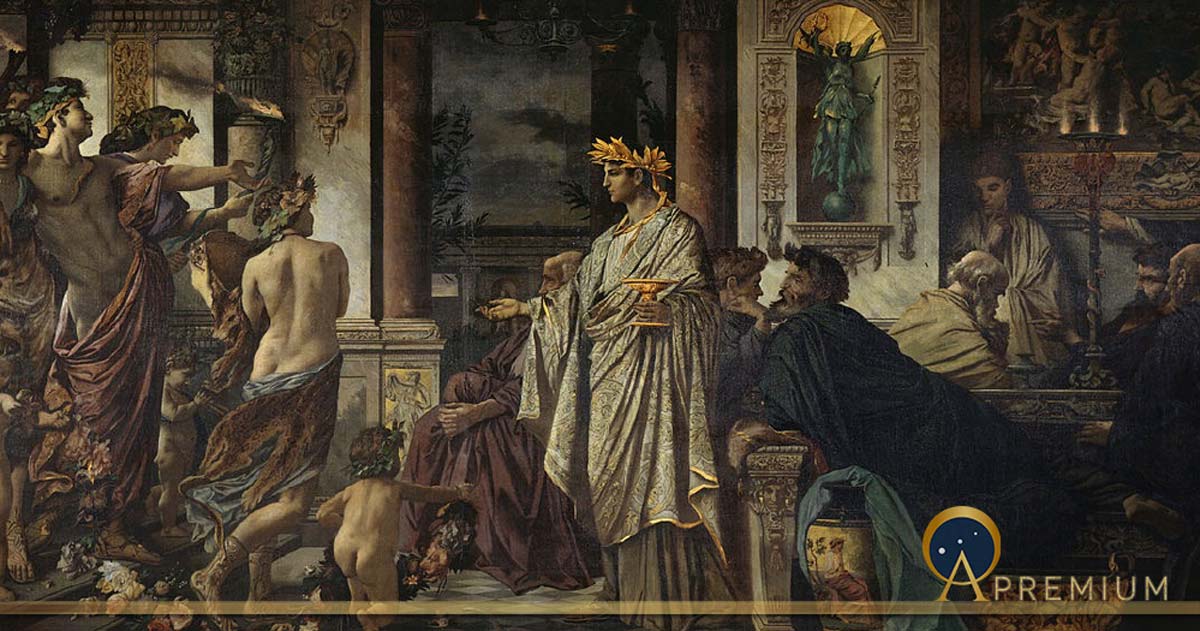

Top Image: Scene from Plato’s Symposium by Anselm Feuerbach (1871) (Public Domain)