Pythagoras’ Claim of Universal Musical Harmony is Wrong, Finds Study

Ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras posited that "consonance," a harmonious combination of notes, arises from specific relationships between simple numbers like 3 and 4. While scholars have attempted psychological explanations, these "integer ratios" are still believed to contribute to the beauty of a chord, with deviations thought to produce "dissonance," an unpleasant sound. Not according to a new study, however, which has challenged Pythagoras’ theories to show that in typical listening scenarios, there isn't a preference for chords to adhere perfectly to these mathematical ratios!

Slight Amounts of Deviation: Not in Sync

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, Princeton, and the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics have challenged Pythagoras's theories in two significant ways, publishing their research in Nature Communications.

“We prefer slight amounts of deviation. We like a little imperfection because this gives life to the sounds, and that is attractive to us,” said co-author, Dr Peter Harrison, from Cambridge’s Faculty of Music and Director of its Centre for Music and Science.

They found that the significance of these mathematical relationships diminishes when considering certain musical instruments less familiar to Western musicians, audiences, and scholars.

These instruments include bells, gongs, xylophones, and other pitched percussion instruments. Specifically, the researchers examined the bonang, an instrument from the Javanese gamelan comprised of small gongs.

Indonesian or Javanese gong chimes, including bonang, front. Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, Arizona (ksblack99/Public Domain)

A Practical Test of Pythagoras’ Music Theory

To investigate this phenomenon, the researchers established an online laboratory, involving over 4,000 participants from the US and South Korea in 23 behavioral experiments. Participants were played chords and asked to rate their pleasantness numerically or adjust individual notes to enhance their pleasantness using a slider. The experiments yielded over 235,000 human judgments.

The experiments examined musical chords from various angles. Some focused on specific musical intervals, prompting participants to indicate whether they preferred them perfectly tuned, slightly sharp, or slightly flat. Surprisingly, the researchers discovered a notable preference for slight imperfections, termed "inharmonicity."

- Theano – A Woman Who Ruled the Pythagoras School

- Babylonian Tablet Confirms Pythagoras Did Not Invent the Theorem Bearing His Name

Western vs Eastern Perceptions of Harmony

Other experiments delved into harmony perception using both Western and non-Western musical instruments, including the bonang, according to a press release by the University of Cambridge.

“When we use instruments like the bonang, Pythagoras's special numbers go out the window and we encounter entirely new patterns of consonance and dissonance. The shape of some percussion instruments means that when you hit them, and they resonate, their frequency components don’t respect those traditional mathematical relationships. That's when we find interesting things happening. Western research has focused so much on familiar orchestral instruments, but other musical cultures use instruments that, because of their shape and physics, are what we would call ‘inharmonic’,” said Dr Harrison, a Fellow of Churchill College.

It was found by the researchers that the consonances produced by the bonang align neatly with the specific musical scale used in Indonesian culture, its country of origin. These consonances cannot be replicated on a Western piano due to the limitations of the traditionally used scale. Notably, it is suggested by the study that the unique consonances produced by the bonang's tones were instinctively appreciated by participants, who were not trained musicians and unfamiliar with Javanese music.

For instance, when a two-note chord is played where one note has precisely half or double the frequency of the other, individuals in the Western world perceive this as an octave. The notes are perceived as harmonious with each other, without any dissonance, resulting in a pleasant sound, reports IFL Science.

Dr. Harrison emphasized that music creation involves exploring the creative potential within a given set of parameters, such as discovering melodies on a flute or experimenting with vocal sounds. He elaborated that the findings suggest that employing diverse instruments can unlock a rich harmonic palette that listeners intuitively appreciate.

This contrasts with much of the experimental music in Western classical music over the past century, which has often been challenging for listeners due to its highly abstract structures. Insights from psychology, like theirs, can inspire the creation of new music that resonates with listeners on an instinctive level. The study indicates an entirely new harmonic language that people naturally grasp without the need for formal study can be unveiled by using different instruments.

Harrison explained that a significant amount of pop music currently attempts to blend Western harmony with local melodies from regions like the Middle East, India, and other parts of the world. He suggested that musicians and producers could potentially improve this fusion by considering their findings and contemplating changes in the "timbre," or tone quality, using carefully selected real or synthesized instruments. He believed that such an approach could enable them to achieve a balance between harmony and local scale systems.

Harrison and his collaborators are actively exploring various instruments and planning follow-up studies to examine a broader spectrum of cultures in the future. Specifically, they aim to gather insights from musicians who utilize "inharmonic" instruments to ascertain whether they possess different harmony concepts compared to the Western participants in the study.

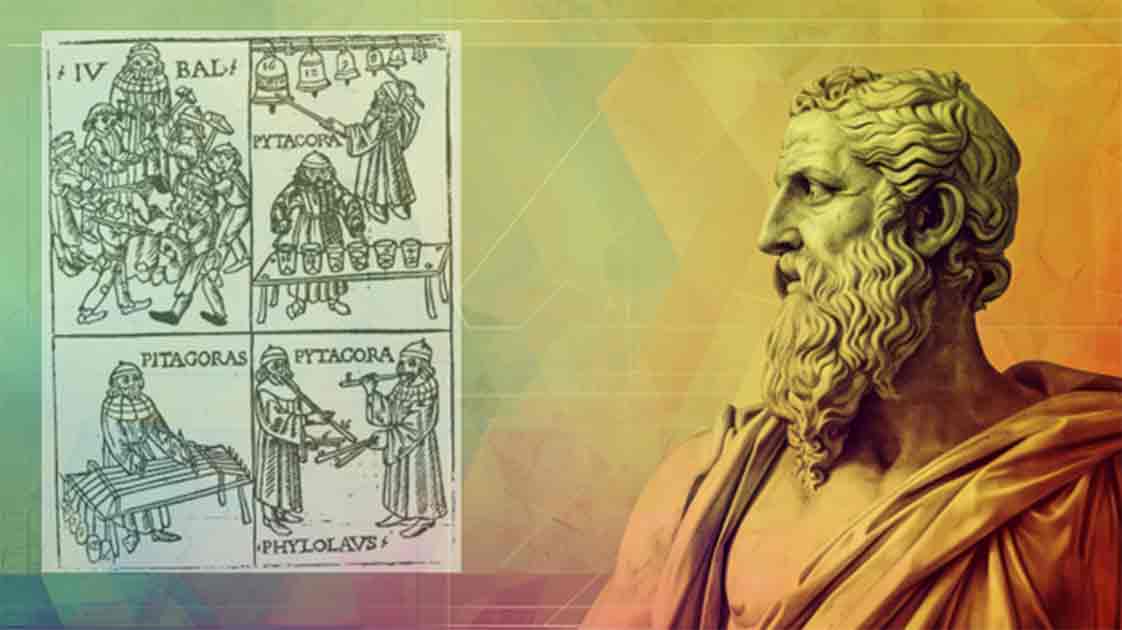

Top image: Greek Philosopher Pythagoras with overlay of woodcut showing Pythagoras with bells, a kind of glass harmonica, a monochord and (organ?) pipes in Pythagorean tuning. From Theorica musicae by Franchino Gaffurio, 1492 (1480?) Source: Khuram Ibn Sabir/Adobe Stock, overlay Bibliothèque nationale de France/Public Domain

By Sahir Pandey

References

Marjieh, R., et al. 2024. Timbral effects on consonance disentangle psychoacoustic mechanisms and suggest perceptual origins for musical scales. Nature Communications, 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45812-z.

Simmons, L. 2024. Pythagoras’ Ideas About “Perfect” Musical Harmony Are Not Quite Right After All. Available at: https://www.iflscience.com/pythagoras-ideas-about-perfect-musical-harmony-are-not-quite-right-after-all-73132.

Stokel-Walker, C. 2024. Pythagoras was wrong about the maths behind pleasant music. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2419442-pythagoras-was-wrong-about-the-maths-behind-pleasant-music/.