Herto Man: A 160,000-Year-Old Window into Homo Sapiens' Ancestry

The Herto Man is a common name for a group of prehistoric human remains that were discovered in 1997, in the Afar Triangle in Ethiopia, in the famed Bouri Formation that yielded many ancient fossils. The Herto Man, in every way an extraordinary archaeological find, represents a crucial chapter in the understanding of human evolution. The fossils have provided invaluable insights into the lives of our ancient Homo sapiens ancestors. Dating back approximately 160,000 years, they have unlocked a treasure trove of information about early human existence, shedding light on anatomical features, cultural practices, and the complex interplay of various hominin species during this period. What secrets have been uncovered about our earliest ancestors?

The Herto Man and the Stories It Could Tell

The discovery and excavation of the Herto Man fossils at the Herto Bouri site in Ethiopia marked a pivotal moment in paleoanthropology, providing a unique window into the distant past of Homo sapiens. Led by Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Dr. Berhane Asfaw, the international team of researchers embarked on an ambitious expedition in 1997, exploring the Middle Awash region of the Afar Triangle.

This vast geographic depression, situated in the northeastern part of Ethiopia, has long been recognized as a treasure trove of paleontological riches due to its unique geological features. The area is part of the East African Rift system, a region where tectonic forces are pulling the African continent apart. This geological activity has exposed layers of sedimentary deposits, creating an ideal environment for the preservation of ancient fossils.

Perspective image of the Afar Depression. (Wikipedia Commons/CC BY 2.0)

The Herto Bouri site, within the Middle Awash region, revealed a series of fossils, with the most notable finds being three well-preserved crania attributed to Homo sapiens idaltu, or the Herto Man. The excavation process involved meticulous care to avoid damage to the delicate remains and employed standard archaeological techniques such as careful digging, screening of sediments, and precise documentation of the stratigraphic context. Keep in mind that some of these remains, being hundreds of thousands of years old, are located at great depths, and removing them can be a difficult process.

The team's efforts were rewarded with the unearthing of three nearly complete adult skulls, dated to approximately 160,000 years ago.

The fossils were embedded in the sediments of an ancient lake, providing a unique opportunity for researchers to study the environment in which these early Homo sapiens lived. The preservation of the fossils was exceptional, allowing for detailed analysis of cranial features, dental morphology, and other anatomical aspects critical for understanding human evolution.

Robert Sanders notes, in a 2003 Berkley University press release:

“The fossil-rich site was discovered on November 16, 1997, in a dry and dusty valley bordering the Middle Awash River near Herto, a seasonally occupied village. During a reconnaissance, White [researcher] first spotted stone tools and the fossil skull of a butchered hippo emerging from the ground. When the team returned to intensively survey the area 11 days later, they discovered the most complete of the adult skulls protruding from the ancient sediment. It had been exposed by heavy rains and partially trampled by herds of cows.” (Sanders, 2003)

- The human skull that challenges the Out of Africa theory

- 50,000-year-old Skull May Show Human-Neanderthal Hybrids Originated in Levant, not Europe as Thought

The discovery of the Herto Man challenged prevailing theories about the timing and pattern of anatomical changes in Homo sapiens. The mosaic of primitive and modern features observed in the crania suggested a more complex evolutionary trajectory than previously thought.

This finding sparked renewed interest in the study of transitional hominins and emphasized the importance of exploring diverse regions for a comprehensive understanding of human evolution. The Herto Man discovery not only expanded our knowledge of early Homo sapiens but also highlighted the collaborative nature of international paleoanthropological research. The interdisciplinary team of scientists, including archaeologists, paleontologists, and geologists, worked together to unravel the mysteries concealed in the layers of sediment at Herto Bouri. This collaborative approach is crucial in piecing together the puzzle of our evolutionary history, drawing on a range of expertise to interpret the significance of these ancient remains.

A Window into Our Most Distant Past

The anatomical features of the Herto Man fossils are a fascinating aspect that has significantly contributed to our understanding of human evolution. Dating back approximately 160,000 years, these remains exhibit a mosaic of traits that challenge traditional views about the linear progression of Homo sapiens. The crania, or skulls, of the Herto Man provide crucial insights into the anatomical complexity and transitional nature of our early ancestors. One of the striking features of the Herto Man fossils is the combination of archaic and modern traits. The crania display robust facial structures reminiscent of earlier hominins, such as Homo erectus, with pronounced brow ridges and a relatively large face. However, alongside these primitive features are unmistakably modern characteristics, including a rounded skull shape and a reduction in the size of brow ridges. This amalgamation of features complicates simplistic notions of an unbroken evolutionary line and emphasizes the intricate nature of human evolution.

The Herto man skull, National Museum of Ethiopia. Sailko/CC BY 3.0

The size and shape of the Herto Man crania are particularly noteworthy. The skulls are relatively large, suggesting a brain size within the range of modern humans. This finding challenges the assumption that increased brain size in Homo sapiens occurred gradually and uniformly over time. Instead, the Herto Man fossils indicate that the evolution of brain size in our ancestors was more complex, with periods of enlargement interspersed with retention of certain primitive traits. Dental morphology is another aspect of the anatomical features of the Herto Man that has been subject to extensive analysis. The teeth show a combination of primitive and derived traits, further supporting the idea of a mosaic pattern in the evolution of Homo sapiens. The wear patterns on the teeth provide clues about the diet and lifestyle of these early humans, offering insights into their ecological niche and adaptation strategies.

The Herto Man, palaeontological collections of the National Museum of Ethiopia. (Public Domain)

The presence of both primitive and modern traits in the Herto Man fossils challenges the prevailing notion of a neat and linear progression from archaic hominins to modern humans. This mosaic nature suggests a complex web of evolutionary changes, with different populations of Homo sapiens adapting to diverse environments and selective pressures. The significance of the Herto Man anatomical features extends beyond the study of Homo sapiens alone. The fossils contribute to the broader discussion about hominin diversity and interactions during the Pleistocene epoch.

Afar Triangle as the Cradle of Human Evolution

The Herto Man fossils not only provide insights into the anatomical evolution of Homo sapiens but also offer significant cultural implications that broaden our understanding of the behaviors and symbolic practices of our ancient ancestors. The cultural aspects inferred from the Herto Man discovery shed light on the cognitive complexity and social dynamics of early Homo sapiens, challenging conventional views on the timeline of symbolic behavior and cultural sophistication. This is due to an interesting feature that the skulls bear - several man-made cut marks and alterations, which could be an insight in complex funerary practices, such as excarnation, the removal of flesh and organs before burial.

In ‘ The Origin and Evolution of Homo sapiens’, 2016, Chris Stringer describes the find thus:

“Several cranial and dental human fossils were recovered from an open site at Herto in Ethiopia in 1997. The most significant consist of a nearly complete adult skull, an immature calvaria and parts of another cranial vault, probably adult. All are very large in size, the adult skull having a capacity of approximately 1450 cm3 (88.48 in3). The length of the skull is outside the range of over 5000 modern crania, but its high and relatively globular shape (except for the occipital) conforms to the H. sapiens pattern.” (Stringer, 2016)

Skull of the six to eight-year-old child, found in 1997, shows evidence of cut marks and polish after death. (Alessandrosmerilli/CC BY-SA 3.0)

One of the adult skulls that were discovered on site shows thin vertical cuts, notably on the bottom of the parietal bone, and on the right temporal line. Another adult skull shows even more cut marks, with “intense modification” to 15 of a total of 24 skull fragments discovered. There are deep cut marks that are indicative of defleshing, notably of the frontal bones, cheekbones, parietals, and the occipital bone. This skull also shows signs of repetitive scraping around the circumference of the braincase, indicating a symbolic act.

The skull of a juvenile person was also modified, showing deep cut marks all along the underside of the skull. Likewise, the base of the skull was “broken into”, and the edges were polished and smoothed. Interestingly, similar practices exist amongst the tribes of Papua. All of this shows us that the Herto Man likely had a set of funerary rituals, and paid great attention to preparing the dead for a proper burial.

Skilled Hunters and Survivors

The Herto man was also very capable when it came to production of tools. On the site, numerous fragments and complete tools were discovered, including stone hatchets, blades, and rudimentary tools. These were made from obsidian, fine-grained basalt, and cryptocrystalline rock. Stone tools were typically crafted through a process called knapping, where stones were struck to produce sharp edges for cutting or scraping. Different types of stone tools, such as handaxes, blades, and scrapers, were utilized for various purposes, including hunting, processing food, and other daily activities. A total of 640 such tools were discovered in the area.

This skull of a seven to eight-year-old Homo sapiens Idaltu child, found in 1997, shows evidence of cut marks and polish after death. (Alessandrosmerilli/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Herto Man was a skilled survivor, and likely thrived in the area of the Afar Triangle for many generations. The area of excavation yielded many animal bones, with evident signs of butchering and eating. The most numerous are carcasses of the hippo. These bear many man-made cut marks, recording a long-lasting butchering tradition. Interestingly, one location yielded numerous corpses of hippo calves as well as adults. So, the Herto Man was likely a skilled hunter that had a prevalence towards consuming hippo. Other than this, they hunted and ate bovines as well.

- Elongated Human Skulls of Peru: Possible Evidence of a Lost Human Species?

- The Oldest Homo Sapiens Skull Ever Discovered (Video)

The Missing Link on the Timeline of Human Development

The Herto Man fossils represent a crucial link in the chain of human evolution, challenging preconceived notions and expanding our understanding of the complex journey that led to the emergence of Homo sapiens. The anatomical features, cultural implications, and insights into hominin interactions gleaned from these remains contribute significantly to the broader narrative of human prehistory. As scientists continue to analyze and interpret the findings from Herto Bouri, the legacy of the Herto Man will undoubtedly continue to shape our understanding of who we are and where we came from.

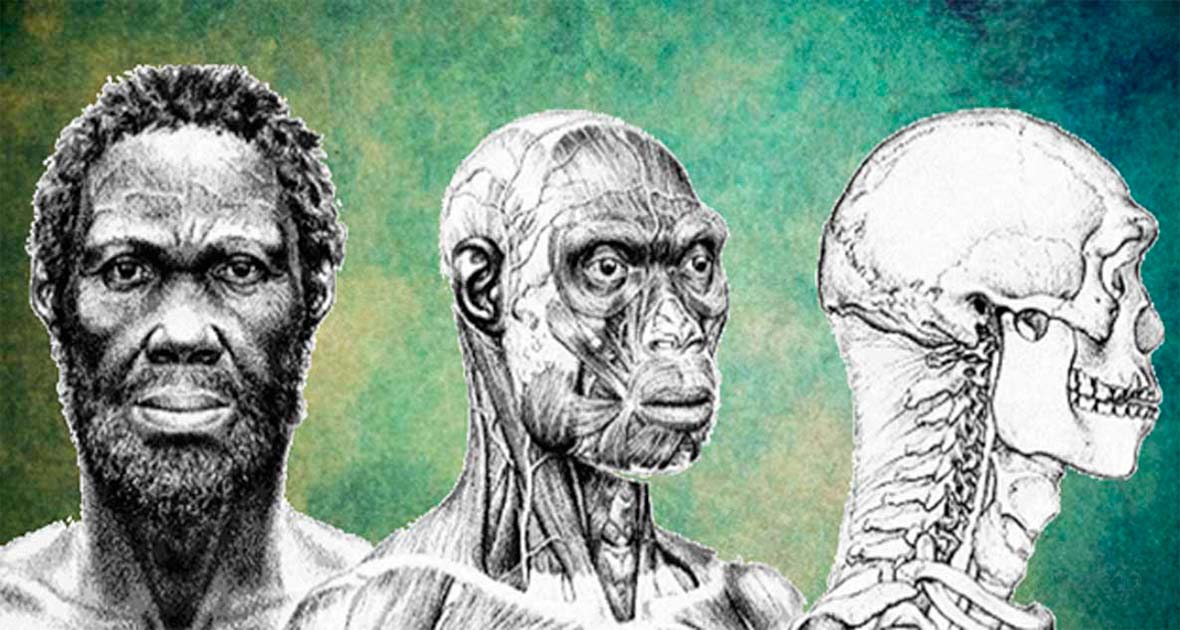

Top image: Depiction of what the ancient 'Herto Man' may have looked like. His skull dates to 160,000 years ago. Source: Bradshaw Foundation

References

Pearson, O. M. 2013. Africa: The Cradle of Modern People. John Wiley & Sons.

Sanders, R. 2003. 160,000-year-old fossilized skulls uncovered in Ethiopia are oldest anatomically modern humans. UC Berkeley News. Available at:

https://newsarchive.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2003/06/11_idaltu.shtml

Stringer, C. 2016. The origin and Evolution of Homo sapiens. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Available at: The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens - PMC (nih.gov)