The Outstanding Story of Osiris: His Myth, Symbols, and Significance in Ancient Egypt

Osiris, the green-skinned god of the underworld, lord of the afterlife and judge of the dead, is one of the best-known gods from ancient Egypt. His story provided his followers with reassurance for life after death, that the Nile would keep their lands fertile, and was an inspiration for what a king should be. He is the only deity that is referred to in ancient Egyptian writings simply as ‘god’ – a surefire indication Osiris was both powerful and popular. Being considered a good god, Osiris was also credited with teaching humanity agriculture, the arts, religion, laws, and morality. And his followers really enjoyed holding festivals in his honor.

Osiris and the Pharaoh

Some scholars have suggested that Osiris may have his origins in Lower Egypt as a very ancient king of Busiris. However it seems more likely that he was the local god of Busiris personifying Underworld fertility. Either way, by 2400 BC Osiris’s role and reach had expanded, as he became linked to the pharaoh. This connection was threefold; first, his story had evolved to include his role as the first king of Egypt – the one who had established the values for later kings to uphold. Second, he was considered the king’s father because he was Isis’ husband and she was said to be the pharaoh’s mother. Finally, Osiris was the higher aspect the pharaoh sought to become after death.

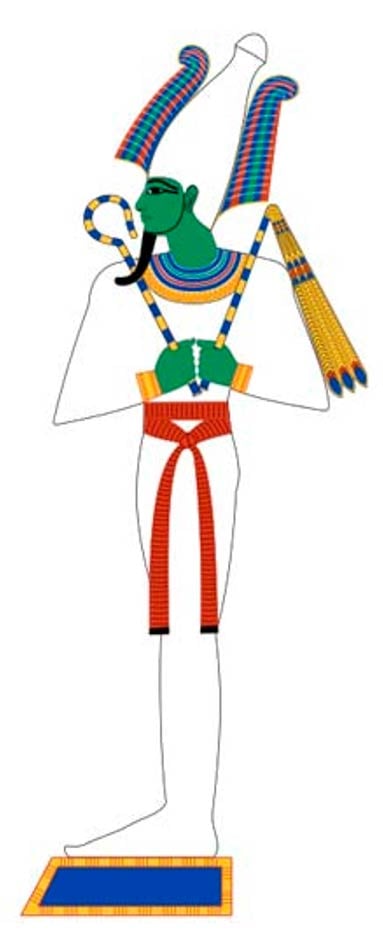

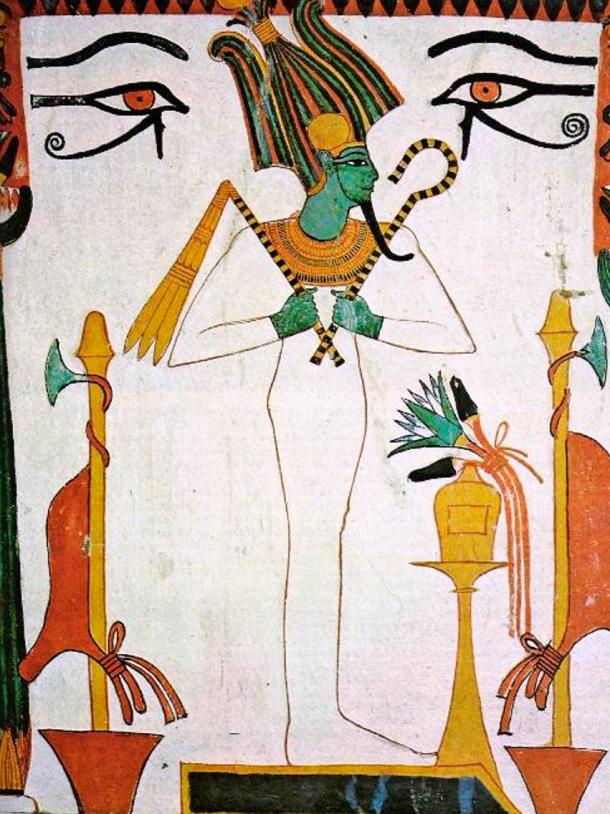

Osiris shown in typical mummy wrappings. Based on New Kingdom tomb paintings. ( CC BY SA 4.0)

A Son of Gods – The Beginning of the Osiris Myth

The name ‘Osiris’ is the Greek form of the Egyptian name Asir (or Wsir or Asar), which may mean “the Powerful”, “the one who sees the throne,” or “the one who presides on his throne.” Later on, Osiris became known as Un-nefer, “to open, appear, or make manifest good things or beauty”.

- Archeologists discover Mythical Tomb of Osiris, God of the Dead, in Egypt

- Zep Tepi and the Djed Mystery: The Book of the Dead and Fallen Civilizations—Part II

From the 5th Dynasty (circa 2513–2374 BC) on, Osiris was also a member of the Ennead (a.k.a. the Great Ennead and the Ennead of Heliopolis), a group of nine Egyptian deities which were worshipped primarily in Heliopolis, but whose influence spread to the rest of Egypt as well. That’s also when Osiris became known as the first child of Geb and Nut.

Geb and Nut were the children of Shu and Tefnut, the creation of the first god, Atum. Osiris’ siblings were Set, Nephthys, and Isis. These three beings played key roles in the Osiris myth.

Outer coffin of Taywheryt depicting Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys. (CESRAS/CC BY NC SA 2.0)

The Myth of Osiris and Isis…and Set

There are some variations on the Osiris myth, but generally the story begins with Osiris as the king of the ancient Egyptians. Either through providing his wife and sister Isis with the power to rule in his place when he was away spreading civilization, or through the other’s pure envy, Osiris angered his brother Set. Set resented Osiris’ success and is said to have conspired to kill his brother after Set's wife Nephthys pretended to be Isis and seduced Osiris. The god Anubis was the result of their union. Some versions say that Set also lusted after Isis.

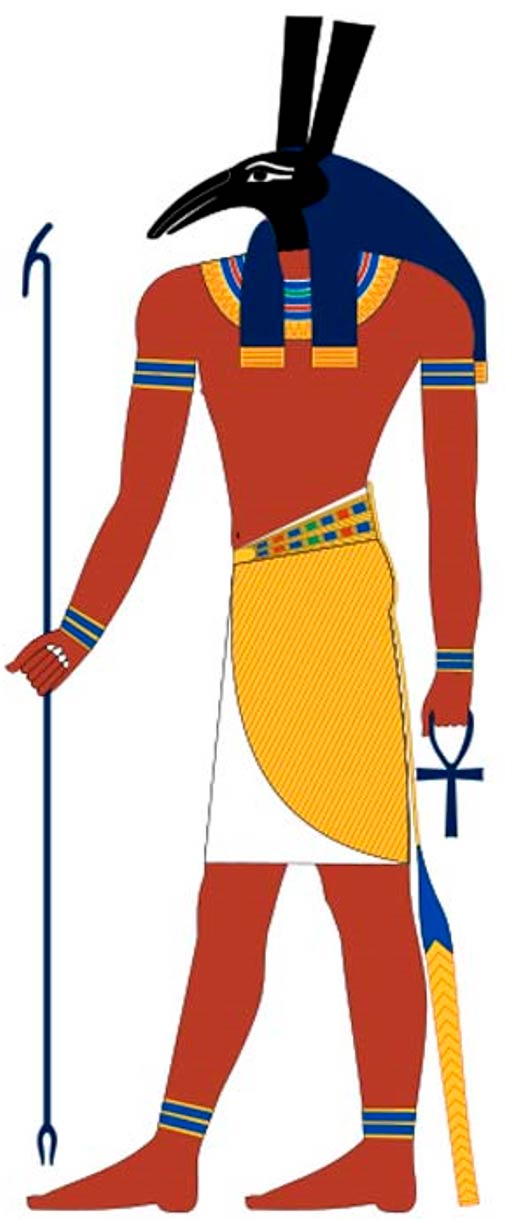

Set, Osiris’ brother and another important ancient Egyptian deity. Based on New Kingdom tomb paintings. ( CC BY SA 4.0)

As an interesting side note, Nephthys was believed to have been barren before she became pregnant with Osiris’ offspring. This part of the myth was later linked to the Egyptian desert flowers which didn’t bloom for years, until a large flood (Osiris) helped the barren land (Nephthys) become fertile and provided them with life (Anubis). Myths also said Anubis honored his father Osiris by giving him the position as the god of the Underworld.

Set soon put a plan in motion to get his revenge. According to Plutarch, Set either drowned or killed Osiris. The story is often said to include a beautiful chest tailor-made to Osiris’ size. Set ordered the creation of the chest and then invited his brother to a banquet. During the feast, he offered the remarkable chest to anyone who could fit inside it. Everyone tried it, but only Osiris fit inside. The moment Osiris laid down in the chest, Set nailed the lid closed. Then he sealed the chest with molten lead and threw it, along with his brother, into the Nile.

The chest (which some say inspired the idea for Egyptian sarcophagi), was carried out to sea and then came to rest in a tamarisk tree growing near Byblos in Phoenicia. The tree grew around the god in the coffin and he remained there until he died. The local king later decided he liked the same tree and, with no knowledge of Osiris’ body inside it, had it turned into a column for his palace.

Rameses III censing and libating before Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, protected by winged Isis. Scene from tomb of Ramses III. (KV11) (Public Domain)

Isis had been out looking for her beloved and eventually happened upon the palace, there she was taken in and cared for the king’s children while disguised as an old woman. When she revealed herself as the goddess after saving one of the king’s sons, the king offered her whatever she wanted. She chose the column and thus Isis found Osiris’ remains.

Revival, Desecration, and Resurrection

The goddess returned to Egypt with her husband and worked to reconstitute his physical body. Then Isis transformed herself into a kite (bird). She used magic words and the beating of her wings to revive him and then conceived a child with him. That child was Horus. She then hid her husband’s body and went off to raise her son.

Horus, Osiris, and Isis: pendant bearing the name of King Osorkon II. ( CC BY SA 1.0 )

But Set encountered Osiris’ body while he was out hunting one day. To prevent his brother from gaining the burial he deserved, the enraged Set cut Osiris’ body up into various pieces, with differing numbers according to the texts: 14 (half of a lunar month), 16 (the ideal height for a rise in the water level in cubits) or 42 (the number of the nomes of Egypt). The body parts were then scattered across Egypt.

Isis discovered what had been done and gathered all of the pieces of Osiris’ body that she could. The only part she could not find was his penis, which had been eaten by an oxyrhyncus fish (making it a forbidden food in ancient Egypt). With the help of Nephthys and Anubis, Isis patched up Osiris’ body the best she could and prepared it for a proper burial. That’s when they created the first mummy and Anubis became associated with embalmers. When the other gods (or at least Ra/Re) saw this, they resurrected Osiris, but because he was incomplete he could no longer rule in the land of the living. So he became the ruler and judge of the Underworld. Horus eventually avenged his father by killing Set and becoming the new king of Egypt.

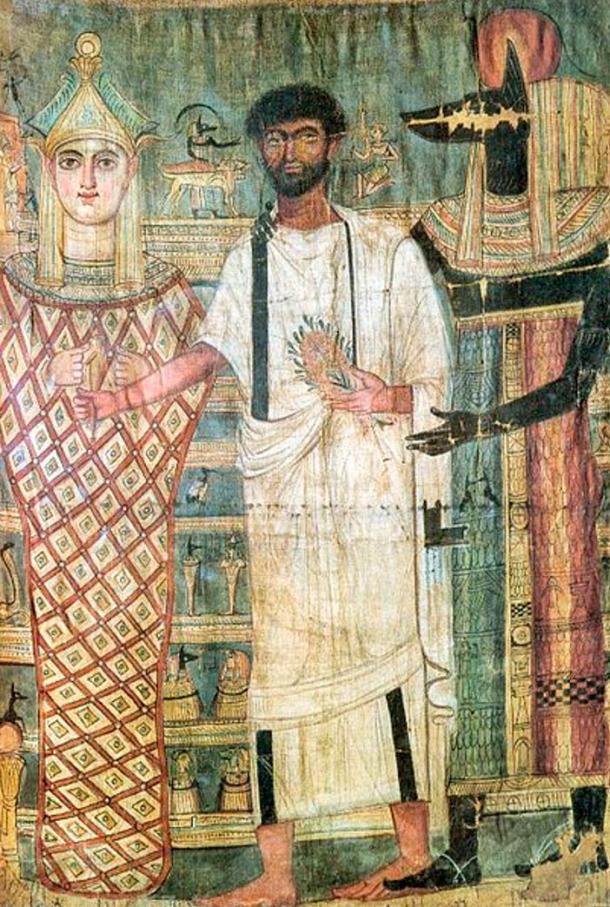

Shroud from the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty showing Osiris and Anubis with a deceased man. (Public Domain)

Osiris as the Egyptian Underworld Deity

Osiris was not an Underworld (Duat) deity to be feared. In fact, his reputation as a good and benevolent king probably created a sense of security for people nearing the end of their lives. Although people did not need to fear the deity himself, it was no easy task to enter his domain. A decent burial, spells from The Book of Coming Forth by Day (better known today as The Book of the Dead) and The Book of Gates, and amulets were provided for the dead to help them make the dangerous journey through the Underworld to the hall of judgement where their heart would be weighed against the feather of Ma’at.

It was pretty much guaranteed that a person who made it that far would be welcomed into the afterlife since the ancient Egyptian judgment did not seek perfection, instead it looked for balance. If the person could convince benevolent Osiris that he or she deserved to be there, they could stay.

The judgement of the dead in the presence of Osiris: Anubis brings Hunefer into the judgement area. Anubis is also shown supervising the judgement scales. Hunefer's heart is weighed against a feather, the symbol of Ma’at. Then Hunefer is brought to the right in the presence of Osiris by his son Horus. Osiris is shown seated under a canopy, with his sisters Isis and Nephthys. At the top, Hunefer is shown adoring a row of deities who supervise the judgement. (Public Domain)

This association with the Underworld provides another explanation why Osiris is often depicted as a mummified pharaoh – dead pharaohs were associated with him and mummified to look like him.

- Judgment in the Hall of Truth and Preparations for the Afterlife

- Has the Hidden Location of the Tomb of Cleopatra Finally Been Found?

Osiris the Agrarian God?

Although it may seem contradictory at first, Osiris was also considered a fertility god – at least in terms of agricultural fruitfulness. But if you look at the agricultural cycle of apparent death and rebirth, you can begin to see some of the reasoning behind this. For the ancient Egyptians, Osiris was symbolically killed and had his body broken on the threshing room floor each harvest. Then the flooding of the Nile took place and the land (his body) was revived once again. These factors can easily be likened to elements of the Osiris myth.

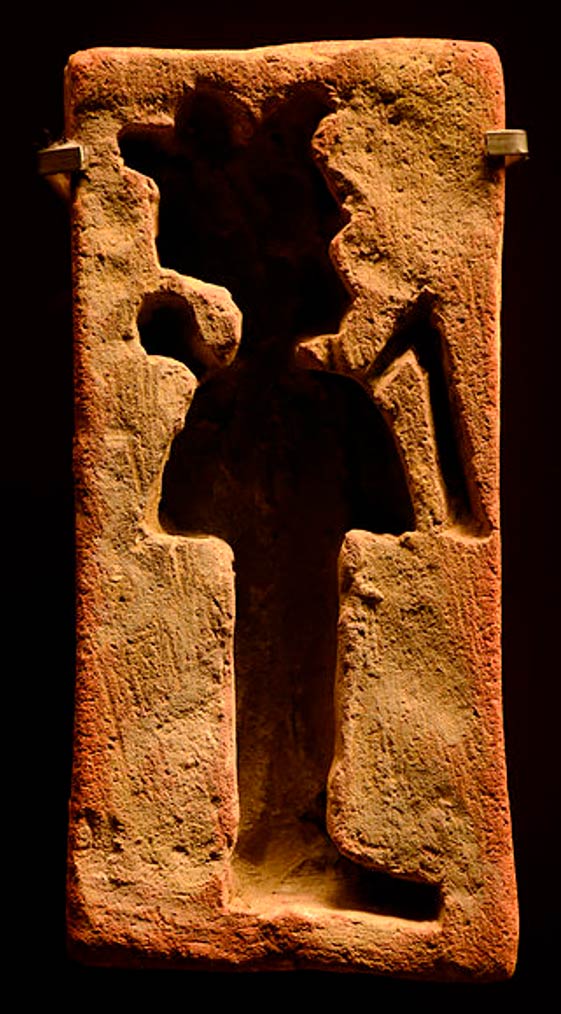

In one agrarian ritual, a dirt figurine was created in a mold to represent Osiris and it was placed in a small sarcophagus. Seeds were planted in that dirt and then watered, creating an “Osiris garden”, or what some have called “grain mummies” or “corn mummies”. When the plants grew from the box it was said that the deity had been brought back to life. Some of these figurines, called Osiris’ Beds’ in that context, have been found in Theban tombs, where they have been found covered in the remains of wheat or barley. Tutankhamen’s tomb provided archaeologists with some fine examples that were made of barley and emmer.

Osiris’ bed, 450 - 300 BC, from Upper Egypt (Gabbanat el-Gouroud), clay. Musée des Confluences. (CC0)

The ancient Egyptians also had a legend stating that their people had been cannibals until Osiris and Isis taught them about then persuaded them to use the practice of agriculture. Although there is no strong evidence to say ancient Egyptians were cannibals, they seemed to like the idea of Osiris having brought order to their civilization.

Osiris’ Symbols

The oldest found representation of Osiris dates back to 2300 BC, but he didn’t really become popular in images until the New Kingdom period (1539–1075 BC). Continuing with the agricultural connections, Osiris’ body was sometimes represented as a field and he was also linked to images of trees – a feature present in practically all the tomb-cenotaphs of Osiris. His skin color also shows this association; if it was green it could represent the rebirth of the vegetation and if it was black it was for the fertile soil of the Nile River valley.

Osiris, Egyptian God of the Underworld. ( Public Domain)

Osiris stands out from most other famous Egyptian deities because he is depicted as human, not an anthropozoomorphic (human/animal) being. Most depictions of the god stress his role as the ruler of the Underworld by showing him wrapped from the chest downwards in mummy bandages. If not in the wrappings, he is shown in a tight-fitting garment.

As a king of Egypt, he was depicted with the Atef Crown - a combination of the Hedjet, the crown of Upper Egypt, with an ostrich feather on each side. His power was shown in the crook and flail in his hands, which are usually crossed in front of his chest, and these items represented the fertility of the land and the king’s authority. Osiris is also shown wearing the long, curved false beard of a dead god.

Another symbol of Osiris is the Djed pillar. This symbolizes the stability and continuation of his power and may represent his spine. The pillar is sometimes decorated with the Atef crown or has two wedjat/udjat-eyes, and it has been decorated with the flail and crook at times as well. This pillar was seen as an important feature and ritually erected in some Abydos festivals. The raising of the Djed pillar was a nod to the resurrection of Osiris – a stable monarch.

A scene on the west wall of the Osiris Hall that is situated beyond the seven chapels and entered via the Osiris Chapel. It shows the raising of the Djed pillar. (Jon Bodsworth)

The Rise of the Osiris Cult and its Rituals

Abydos was the center of the Osiris cult because the ancient Egyptians believed the deity’s head had been buried there. The city’s necropolis was the most popular choice for a burial, if the person could afford it and had a high enough status to be laid to rest near the deity. The next best option was placing a stele with the deceased’s name near the site.

Head of the God Osiris, ca. 595-525 BC. (Brooklyn Museum)

Busiris (Djedu) was another important Osiris sanctuary and it is where one could see the name of the city written with two Djed pillars. A third key site for the followers of Osiris was Biggah (Senmet). This small island was where Osiris’ body is said to have rested. But the reach of the Osiris cult was much wider since all the cities which claimed to have been a location where a part of his dismembered body was buried also had a cenotaph to the god.

Although deceased kings were originally the only ones to associate themselves with Osiris upon their deaths, by 2000 BC every dead man could be linked to the deity. The association with Osiris signified not resurrection itself, but the renewal of life in the next world and through one’s descendants. His popularity was cemented with the god’s benevolent nature in the afterlife as well as his role in creating order and law. People saw him as a god who could protect them during their lives and who would judge them fairly in the Underworld.

By making Osiris more accessible, he also became more popular and his cult spread throughout Egypt, sometimes with the god joining or absorbing other fertility and Underworld deities. This ability to incorporate the local gods enabled Osiris worship to remain prominent through to the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Serapis, for example, was a Hellenistic god that combined Osiris with Apis - the sacred bull of Memphis. Greco-Roman writers also saw connections between their god Dionysus (Bacchus) and the Egyptian deity. Osiris only fell with the rise of Christianity. But that hasn’t stopped scholars from noting some similarities between that religion with the ancient Egyptian god’s story.

Bust of Serapis. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from the 4th century BC, stored in the Serapeum of Alexandria. (Public Domain)

Although Osiris was the Judge of the Dead, he was also associated with rebirth, so the festivals related with him tended to focus more on celebrating life. This has already been noted with the Osiris figurines to enhance agricultural fertility.

Processions and nocturnal rituals also took place at his temples and aspects of his life, death, and rebirth were key elements of those rites. Osiris’ death was honored at the festival of the Fall of the Nile and his resurrection was celebrated in the Djed Pillar Festival. The following section of a hymn to Osiris suggests just how popular his festivals, and the god himself, were to the ancient Egyptian people:

Unto thee are offerings made by all mankind, O thou lord to whom commemorations are made, both in heaven and in earth. Many are the shouts of joy that rise to thee at the Uak festival [the 17th and 18th days of the month Thoth], and cries of delight ascend to thee from the whole world with one voice. Thou art the chief and prince of thy brethren, thou art the prince of the company of the gods, thou stablishest right and truth everywhere, thou placest thy son upon thy throne, thou art the object of praise of thy father Seb, and of the love of thy mother Nut. Thou art exceeding mighty, thou overthrowest those who oppose thee, thou art mighty of hand, and thou slaughterest thine enemy. Thou settest thy fear in thy foe, thou removest his boundaries, thy heart is fixed, and thy feet are watchful. Thou art the heir of Seb and the sovereign of all the earth. Thou hast made this earth by thy hand, and the waters thereof, and the wind thereof, the herb thereof, all the cattle thereof, all the winged fowl thereof, all the fish thereof, all the creeping things thereof, and all the four-footed beasts thereof. O thou son of Nut, the whole world is gratified when thou ascendest thy father's throne like Ra. Thou shinest in the horizon, thou sendest forth thy light into the darkness, thou makest the darkness light with thy double plume, and thou floodest the world with light like the Disk at break of day. Thy diadem pierceth heaven and becometh a brother unto the stars, O thou form of every god. Thou art gracious in command and in speech, thou art the favoured one of the great company of the gods, and thou art the greatly beloved one of the lesser company of the gods.

- The sacred symbol of the Djed pillar

- Enigma of the Heartless Pharaoh: Who Stole the Heart of King Tut, and Why?

Posthumous stele of Amenhotep I and Ahmose-Nofretary making an offering to Osiris. Limestone. New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, reign of Amenhotep III, c. 1390-1352 BC. Probably from Thebes. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Another important aspect of Osiris worship was to present dramatic passion plays reflecting the life, death, mummification, and resurrection of the deity. The plays involved local priests and important community members and the mock battles between The Followers of Horus and The Followers of Set were open to anyone. Some scenes were especially violent and there are even cases noted of the staged violence having become real and leading to deaths.

Once the battle was won by the Followers of Horus, the festival-goers celebrated by carrying out the golden statue of Osiris from the temple’s inner sanctum, so everyone could lavish it with gifts. It was then paraded around the city and finally placed at an outdoor shrine so the god could witness the festivities and people could admire him. This removal of the statue from the darkness of the temple also reflected on Osiris’ resurrection.

Late Period–Ptolemaic Period statue of Osiris. (CC0)

Top Image: Osiris. Source: SaraForlenza/Deviant Art

By Alicia McDermott

References

Crystalinks. (n.d.) ‘Osiris.’ Crystalinks. Available at: http://www.crystalinks.com/osiris.html

Hill, J. (2008) ‘Osiris.’ Ancient Egypt Online. Available at: https://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/osiris.html

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019) ‘Osiris: Egyptian God.’ Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Osiris-Egyptian-god

Tour Egypt. (2019) ‘Egypt: Gods - Osiris, Asar.’ Tour Egypt. Available at: http://www.touregypt.net/osiris.htm

Benderitter, T. and Hirst, J. (trans.) (2019) ‘Osiris.’ Osirisnet: Tombs of Ancient Egypt. Available at: https://www.osirisnet.net/dieux/osiris/e_osiris_01.htm

Myths and Legends. (2019) ‘Osiris.’ Myths and Legends. Available at: http://www.mythencyclopedia.com/Ni-Pa/Osiris.html

Canadian Museum of History. (n.d.) ‘Mysteries of Egypt: Egyptian Civilization - Osiris.’ Canadian Museum of History. Available at: https://www.museedelhistoire.ca/cmc/exhibitions/civil/egypt/egcrgo1e.html

Comments

Thnx