Delighted Maori Recover ‘Hidden’ Waka Canoe in New Zealand River

A long-abandoned waka, the traditional canoe of the Maori people, was recently discovered in the shallow waters of the Patea River in the Taranaki region of western New Zealand. Current estimates are that the vessel is more than 150 years old. Local people have speculated that it was intentionally hidden by their Maori ancestors to prevent it from being confiscated by the British colonial government in the 19th century.

Identifying the Maori Waka Canoe

Fittingly enough, the canoe was found by several Maori who were walking along the banks of the river. The waka was stuck in the mud at the river’s edge, easily identifiable because of its long, curved shape.

“To us it was found because of this kōrero [conversation] about a tohu [a sign] that happened about three weeks ago when tuna were found on the beach at Te Patea,” a local Maori elder, Ngapare Nui, told Te Ao Maori News. “They had to find out how our taonga [valuable treasure] passed away… they came up here and they were looking to see if there was any more dead tuna along the river here and that's when they came across the taonga, the waka here.”

- The Maori: A Rich and Cherished Culture at the World’s Edge

- The Bullroarer: An Instrument That Whirls Through Cultures and Time

Shortly after the discovery, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage was summoned to investigate. “As soon as I saw it, I knew it was a waka from the old people because it was made of totara,” said South Taranaki Maori historian Darren Ngarewa, in an interview with New Zealand’s 1 News.

Ngarewa explained that wakas were traditionally made from the totara tree, a native species in New Zealand that was ideal for canoe making because of its light weight and natural resistance to rotting and splitting. The totara tree disappeared from the coastal region of Taranaki many decades ago, which is why its use to make this particular waka was so revealing.

Recovering a Maori Waka Hidden During New Zealand Wars

There were three Maori iwi, meaning nations or peoples, living in the southern region of Taranaki in the 19th century: the Te Pakakohi, Ngati Ruanui and Nga Rauru (Darren Ngarewa is a member of the Ngati Ruanui iwi). At this time these groups were at war with the British colonial government of New Zealand, which had become eager to seize Maori lands to make room for incoming British farmer-settlers.

Maori warriors in a waka canoe. “The blowing up of the Boyd Steele” by Louis John Steel. (Public domain)

In 1869, there was a notorious event in the so-called New Zealand Wars (also known as the Land Wars or Maori Wars) that is still remembered by modern Maori who inhabit the area. During a raid in that year, colonial forces captured the highly respected Maori chief Ngawaka Taurua along with several iwi elders.

During the skirmish, the men were imprisoned in a concentration camp in Otago, along with many other captured Maori warriors and civilians. Because of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions in the camp, the casualty rate among the indigenous people who were taken there was high.

In addition to their other atrocities, the colonial government forces confiscated or destroyed any wakas they found in order to prevent Maori warriors from traveling freely by water. The Maori who discovered the waka in the Patea River believe locals may have hidden it in or around 1869, to make sure it didn’t fall into the wrong hands.

They may have intended to retrieve the long canoe later. But for one reason or another it remained hidden in the shallow river waters for more than a century-and-a-half, somehow eluding observation until now.

“We have spent so long reclaiming ourselves after so much interference by the Crown so to rediscover a part of our missing history, particularly on the 154th anniversary, is big for us,” said Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, a leader of the local Ngati Ruanui iwi.

“This is not something we talk about, because of the pain we suffered,” Ngarewa added. “But with the waka coming out and the way it was coming out, it was unfolding as part of a bigger picture. Now maybe is the time to tell our story.”

War Speech by Augustus Earle. An unknown Maori chief addressing a crowd of warriors alongside their waka canoes. (Public domain)

The Story of the Waka, an Indispensable Maori Innovation

The history of the waka is essentially synonymous with the history of the Maori people in New Zealand. The original Polynesian Maori settlers landed in New Zealand between 1250 and 1300, and it was the waka that carried them to their destination.

The oldest ancient waka ever recovered in New Zealand was dated to approximately the year 1400, with most other discoveries dating back to between the 16th through mid-19th centuries. Nevertheless, ancient canoes found on various Polynesian islands are remarkably similar in design to the Maori waka, leaving little doubt that the Maori brought this technology with them when they arrived.

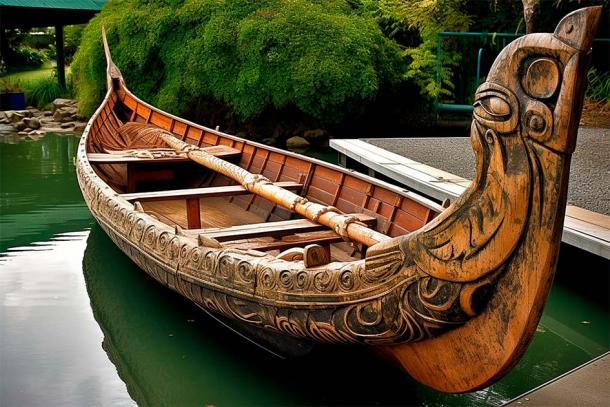

Traditional Maori waka canoe boat. (Matthew / Adobe Stock)

The interior of the waka would be painstakingly carved out of an intact totara log, which might weigh as much as three or four tons in some cases. Using stone tools, the entire process of carving, shaping and finishing the waka canoe could take up to a year or more to complete. The craft were often elaborately decorated and painted before being launched, displaying cultural images that had vital meaning to the different iwi that built them.

Waka came in various sizes, ranging from small craft suitable for tight river navigation, like the one that has just been found, to 130-foot (40-meter)-long canoes made for warfare or ocean travel. These bigger wakas had room for 80 paddlers, although the Maori generally attached temporary sails for maximum speed when traveling across the waters of the Pacific.

In regions like the Taranaki the waka were indispensable. They were used for inland travel up rivers and for ocean travel along the coastline. They were adapted for fishing and for the harvest of other types of marine life. They were also critical for ancient naval operations; as Maori seaborne patrols would be dispatched to protect coastal peoples from outside invaders.

- Dizzying Inca Rope Bridges Were Grass-Made Marvels of Engineering

- Snow Goggles Are Masterpiece of Inuit Indigenous Innovation

While the technology of the waka was never completely abandoned, its decline in the modern era can be traced to the outbreak of the New Zealand Wars, which lasted from 1845 to 1872. Understanding the importance of the waka to the rebellious Maori, the colonial authorities ordered the sinking or confiscation of any canoes they could find, and that policy reduced their stock dramatically.

After the conflict ended in Maori defeat and colonization, the surviving iwi began to adopt more European technologies. They became enamored of the small exploratory vessels carried on the large ships of European explorers who came to the islands in the mid-to-late 19th century, like Captain James Cook and the Frenchman Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne.

Soon the waka were being replaced by these smaller and more maneuverable boats. The totara tree was no longer as plentiful on the islands as it used to be, which was yet another factor that led to the decline in prominence of the waka.

Maori waka canoe on display at Otago Museum. (Public domain)

Proud Culture and Tragic History Revealed by Waka Canoe

While the waka may not have been built and used as frequently over the last 150 years, the Maori people still view it as a foundational technology that helped shaped the development of their culture. That is why this new discovery has created so much excitement among the people who’ve occupied the Taranaki region for 700 years.

After being carried out of the mud by a team of a dozen or so locals, the newly salvaged waka was airlifted from the site by helicopter, and has now been taken to the city of New Plymouth to be restored. No decision has been made about the canoe’s ultimate fate.

The iwi of Taranaki would like to see the waka put on display close to where it was recovered. In this way it could be used as an educational tool to inform younger generations about their cultural roots and about the terrible oppression the Maori experienced during the bloody New Zealand Wars. “This is much bigger than just us, for the hapu [Maori clans] and iwi,” Ngarewa stated.

Top image: Screenshot of recently discovered traditional waka canoe. Source: Screenshot/1 News

By Nathan Falde