KV62, Designed to Confound: Wealth of Mysteries in the Curious Tomb of Tutankhamun—Part II

Egyptological scholars are divided over whether a right-hand turn to the burial chamber in an Eighteenth Dynasty tomb signifies that it belonged to a female pharaoh. With this feature present in the crypt of Tutankhamun, it is suggested that the boy-king was laid to rest in a second-hand sepulcher intended for a female predecessor. But, there is no consensus in this matter; however, several other discrepancies in the design and layout of KV62 hint that something strange transpired when the young king died. The race is on to unravel not just the many secrets, but also determine if Queen Nefertiti was the tomb’s original occupant in her ultimate role as king.

Detail from one of Tutankhamun’s shabtis inscribed with Spells from the Book of the Dead. Amarna artistic influence notwithstanding, the prominent breasts and low slender hips of a few examples, including this one, have led some experts to suggest it was made for a female predecessor. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Tomb Usurped for Teenage Pharaoh?

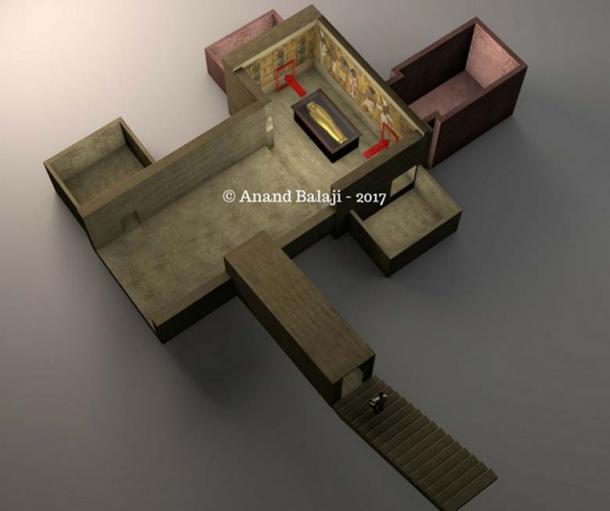

Some scholars are convinced KV62 was never intended to be Tutankhamun’s final resting place; and suggest it was a stop-gap arrangement owing to his untimely death. Analysing the floor plan of KV62, Dr Marianne Eaton-Krauss avers that additions were made to the original, single chamber (Antechamber only) to include the Annexe, Burial Chamber, and Treasury. “The tomb which Carter discovered in 1922, KV62, was not originally intended for Tutankhamun’s interment – nor, for that matter, for the burial of any pharaoh. Its plan does not meet the requirements for a king’s tomb that had evolved from Thutmose III’s reign down through the time of Amenhotep III, and which the Royal Tomb at Amarna also exemplifies. Instead, KV62’s original plan conformed to the modest type of tomb suitable for lesser members of the royal family – kings’ sons and daughters, as well as wives – given burial in the Valley of the Kings during the Eighteenth Dynasty,” she maintains.

- The Elusive Tomb of Queen Nefertiti may lie behind the walls of Tutankhamun's Burial Chamber

- Bust of Contention: Controversy erupts as the Younger Lady is dubbed Nefertiti—Part I

The door on the right-hand side of the outermost shrine of Tutankhamun (Carter no. 207) depicts a seated divinity wearing the twin feather headdress, ram’s horns and grasping an ankh sign. This rectangular panel is surrounded by decorations of the double tyet-knot amulets of Isis and djed hieroglyphs of Osiris, all set against a brilliant blue faience background. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Moreover, it is quite obvious that the burial area was not designed to contain the regal nest of huge gessoed and gilt shrines that caused extreme difficulties for Howard Carter when disassembling them. Concurring with Marianne’s proposal, Egyptologist, Dylan Bickerstaffe, informs, “It was thought that Tutankhamun intended to be buried elsewhere – perhaps in TA27 or TA29 at Amarna; and perhaps, following the return to Thebes, in WV23, the tomb later occupied by Ay. In which case the question is: who was KV62 originally intended for? There are similarities in design to the King’s Valley tomb of Yuya and Thuya (KV46), and it is therefore not impossible that it could have originally been intended for an Amarna woman, perhaps even Nefertiti.

“Tutankhamun was buried in front of the scenes on the north wall, so there is no reason why Nefertiti, Meritaten, Baketaten, or anyone else, should have needed to be buried behind these scenes – which, after all, are not quite like the scenes which occupied the far side of well shafts in other 18th Dynasty royal tombs, having the additional opening of the mouth scene. Indeed it is this specific scene which Reeves says betrays evidence of adaption from a previous owner, and it is curious that the area around this also has the greatest concentration of mould spots.”

- The Mysterious Disappearance of Nefertiti, Ruler of the Nile

- Nefertiti and a Rush of Scans: Race to find Double Burial Gathers Steam—Part I

Conflicting and inconclusive results were obtained from tests based on a theory by Dr Nicholas Reeves that said KV62 extended beyond its north and west walls; where Nefertiti, it was touted, would be found buried—probably with her full pharaonic assemblage. (Anand Balaji/DepositPhotos.com)

Too Young to Die

“At the time of Nefertiti’s burial within KV 62 there had surely been no intention that Tutankhamun would in due course occupy this same tomb. That thought would not occur until the king’s early and unexpected death a decade later,” states Dr Nicholas Reeves. The non-traditional 20-square “Amarna grid” images depicted on the north wall aside, Reeves created quite a stir when he claimed that the figure who is shown performing the Opening of the Mouth ceremony is not Pharaoh Aye as has traditionally been believed, but Tutankhamun himself carrying out the ritual for the deceased Nefertiti.

Limestone fragment with cartouche of Neferneferuaten Nefertiti. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (Public Domain)

“Possibly, by the time Tutankhamun’s burial came to be robbed shortly after the funeral, Nefertiti’s presence behind the north wall “blind” was already forgotten; perhaps, and more likely, the robbers simply had insufficient time to investigate, choosing to focus instead on those abundant riches readily to hand. Three and a half thousand years later Howard Carter had the time, but he lacked the technology to see beneath the tomb’s painted walls. Accepting the oddly positioned rock-cut niches as evidence that the Burial Chamber’s walls were completely solid, he brought his search to a close – wholly unaware that a more significant find by far may have been lying but inches from his grasp.”

- Press Announcement: Radar Scans Reveal Hidden Chamber in Tutankhamun Tomb with 90 Percent Certainty

- More Evidence Supports Claim Hidden Chamber in Tutankhamun Tomb Contains Another Burial

Tutankhamun as Amun wearing the tall twin plumes that were part of this state god´s iconography. His face shows a gentle childlike quality, and we can assume it was carved quite early in his reign. From Karnak Temple. Luxor Museum.

The Fate of Queen Nefertiti

Could it be that Nefertiti’s tomb was found in ancient or modern times and her burial goods dispersed or destroyed? Dylan Bickerstaffe shares his views: “A more tangible piece of evidence, apparently relating to the burial of Nefertiti, was discovered most probably during illicit excavations in the royal wadi during the early 1930s. A fragment from a calcite shabti bearing Nefertiti’s name was sold by the dealer, Maurice Nahman, to the Brooklyn Museum, in 1932. Another piece of this shabti was discovered in the Louvre, Paris, by Christian Loeben in the 1980s, permitting a reconstruction of the text to be made. Since nothing else belonging to Nefertiti was found in association with the royal tomb, this sole shabti is perhaps to be interpreted as a votive item, placed by her in Akhenaten’s burial. The probability is that Nefertiti’s tomb has yet to be discovered.”

If an Amarna cache or tomb lies hidden, it should contain shabti figurines for Smenkhkare, because “… although examples are known for the rest of the royal family, not even a fragment of one survives bearing his name,” explains Peter Clayton. So, whether Nefertiti lies buried in an extended part of KV62, or elsewhere; her tomb, if discovered in the Valley of the Kings – and more importantly, as Pharaoh – will toss all our beliefs about her final days straight out the window.

The author expresses his gratitude to Dr Nicholas Reeves and Dylan Bickerstaffe for permitting the use of select extracts from their academic papers.

[The author thanks Heidi Kontkanen for granting permission to use her photographs in this series.]

Top Image: Detail from the outermost shrine of Tutankhamun showing a seated deity ; design by Anand Balaji (Photo credit: Anand Balaji); Deriv.

By Anand Balaji

Independent researcher and playwright Anand Balaji, is an Ancient Origins guest writer and author of Sands of Amarna: End of Akhenaten.

--

References:

Nicholas Reeves, The Burial of Nefertiti?, 2015

Dylan Bickerstaffe, Did Tutankhamun Conceal Nefertiti?

Nicholas Reeves and Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Valley of the Kings, 2008

Aidan Dodson, Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation, 2009

Howard Carter and A.C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen, 1977

Nicholas Reeves, The Amarna Dead in the Valley of the Kings, 2003

Nicholas Reeves, The Enduring Mystery of KV55, 1997

Marianne Eaton-Krauss, The Unknown Tutankhamun, 2016

Nicholas Reeves, The Tombs of Tutankhamun and his Predecessor, 1997

Peter A. Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt, 2006

Nicholas Reeves, The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure, 1990