Fact or Fiction? The Obscure Origins of the Greek Alexander Romance

The Greek Alexander Romance, often referred to as a ‘pseudo-Callisthenes’ production, is in one form or another one of the most influential and widely read books of all time; it has birthed a whole literary genre on Alexander the Great and his campaigns across the Persian Empire. But where and when did it first appear and what did it originally look like? Which earlier accounts did it absorb and what is its relationship to the mainstream Alexander histories? Most importantly, does it contain unique factual details?

Where Fiction Met Fact

There are many episodes in the story of Alexander when it is hard to be sure just where the historical element ends and ‘romance’ begins, and by tradition, much legendary material had already infiltrated biographies of the Classical period. But for the Greeks the stories of the past were literally mythoi, and the segregation between myth, legend, and the factual past was a soft border blurred by Homeric epics and Hesiod’s Theogonia, which permitted a coeval interaction between men, heroes, and gods. So, the emergence, and development, of the Greek Alexander Romance, in the Hellenistic world, is perhaps not surprising.

- Alexander the Great: Was he a Unifier or a Subjugator?

- Tomb of Alexander the Great already found, archaeologist claims, but findings have been blocked by ‘diplomatic intervention’

- Alexander the Great Destroyer? The Sacking of Persepolis and The Business of War – Part I

Alexander Mosaic, Naples National Archaeological Museum. (Public Domain)

As far as the Romance, separating the fact from the fabulae has, indeed, proved no easy task, for material was added through a gradual process of accretion, a dilemma encapsulated in Peter Green’s biography of the Macedonian king:

“… the uncomfortable fact remains that the Alexander Romance provides us, on occasion, with apparently genuine materials found nowhere else, while our better-authenticated sources, per contra, are all too often riddled with bias, propaganda, rhetorical special pleading or patent falsification and suppression of evidence.”

This is a warning that not only does the Romance contain some valuable and unique elements of truth, but that the mainstream biographies we rely on when excavating Alexander from the frail manuscripts from the past, contain elements of clinical fabrication, principally from personal agenda.

Birthing a Legend

Attributing the Romance in its earliest form to a single author or date remains impossible, but evidence suggests that both the unhistorical and the quasi-historical elements were in circulation in the century following Alexander’s death. The oldest text we know of today, recension ‘A’, is preserved in the 11th century Greek manuscript known as Parisinus 1711; the text titled The Life of Alexander of Macedon most closely resembles a conventional historical work, though any factual narrative is just the early backbone to which other elements were attached.

17th-century manuscript of an Alexandrine novel (Russia): Alexander exploring the depths of sea. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Recension A, while poorly written, full of gaps, and clearly a syncretic account, is nevertheless the best staging point scholars have when attempting to recreate an original (usually referred to as ‘α’ – alpha) dating back some 700 or 800 years (or more) before the extant recension A. We cannot discount an archetype that may have been written even earlier still, in the Ptolemaic era. If Alexander’s official court historian, Callisthenes, was once credited with its authorship (thus ‘pseudo-Callisthenes’), the prevailing belief must have been that it emerged in, or soon after, Alexander’s Asian campaigns.

Herma of Alexander (Roman copy of a 330 BC statue by Lysippus). (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Through the centuries that followed, the Romance evolved and diversified into a mythopoeic family tree whose branches foliaged with the leaves of many languages, faiths, and cultures; more than eighty versions appeared in twenty-four languages.

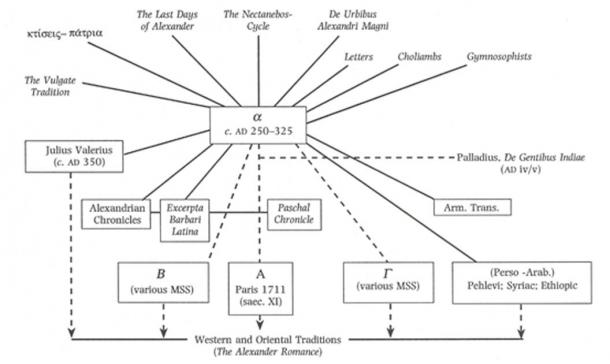

The Alexander Romance stemmed from recension ‘α’, which may itself be an embellished descendent of an earlier archetype. Provided with the kind permission of Oxford University Press to ‘In Search of the Lost testament of Alexander the Great’ by David Grant and copied from PM Fraser ‘Cities of Alexander the Great’, Clarendon Press.

The Hellenistic Pottage

The Hellenistic world in which the book was born, and which gravitated around the kingdom of Alexander’s generals and their dynasties, saw exotic tales arriving from the fabled lands of Kush to the south of Egypt and from the distant East, carried down the Silk Road with the help of the settlements Alexander founded (or simply renamed) along its route. According to Strabo, who studied in Egyptian Alexandria, the ‘city’ of Alexandria Eschate (‘the furthest’) in the Fergana Valley had brought the Greek settlers and the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom into contact with the silk traders of the Han dynasty of the Seres (the Chinese) as early as the third century BC.

- In Search of The Lost Testament of Alexander the Great: Excavating Homeric Heroes

- “But In Case Anything Should Happen”: Wills and Covenants in the Age of Alexander the Great

- The Romance of Alexander the Great: Are the Legends Really True?

Ptolemaic Egypt fostered trade eastward as far as India with the help of Arabs and Nabateans, and the resulting contact fertilized Hellenistic literature. Under Ptolemy II Philadelphos, in the generation immediately after Alexander, Greek influence extended to Elephantine, an island in the Upper Nile that marked the boundary with Ethiopia, perhaps an early center of the ivory trade. State-employed elephant hunters would disappear into the African interior for months at a time once the Seleucids cut the Ptolemies off from their supply of Indian war elephants; they would return with animals never before seen and which became ‘objects of amazement’. In this environment, the Romance soon absorbed the ‘wonders’ that were attaching themselves to Alexander and in time it metamorphosized into something of a book of fables that became a multicultural depository of traditions that grew up around the king.

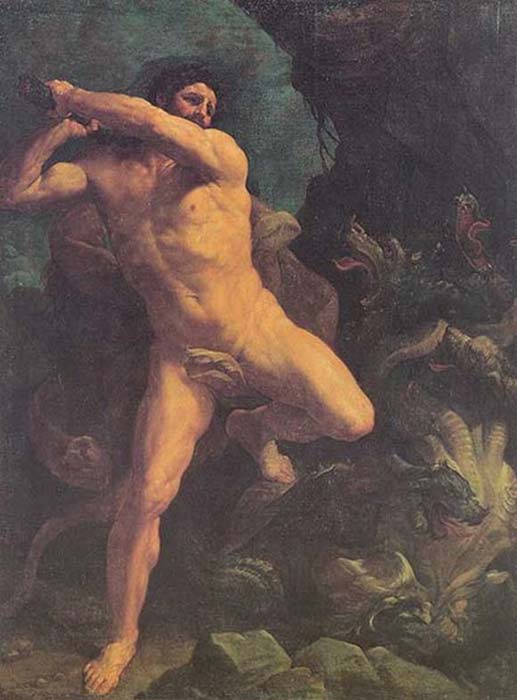

But Alexander had established his own romance, even in his life. Callisthenes, along with the historian Anaxarchus, had annotated Aristotle’s copy of Homer’s Iliad (the ‘Recension of the Casket’); Alexander is said to have kept the edited scrolls close. Reliving the epic Iliad, in which the ‘temporal boundary between the ages of myth and history is in fact a fuzzier, less distinct line than appears at first glance’, was a role that suited Alexander, who took a firmly euhemeristic stance when tracking down his heroes. He believed he was following in the footsteps of Heracles and Dionysus the conqueror of the Orient, and with a sense of honor and duty that his Greek Homeric education and this homage would have bestowed.

Heracles and the Hydra, Guido Reni, 1620. (Public Domain)

Cementing the foundations of Alexander’s own divine myth, and one appropriately born in Egypt, was an episode at the Siwa Oasis and its cult to the composite god Zeus Ammon, with ties to East and West. The priest’s allegorical slip of the tongue rendered ‘ O, Paidion’ (‘O, my son’) as ‘ O, pai Dios’ (‘O, son of God’, thus Zeus). We have no evidence of formalities to proclaim Alexander pharaoh at this time except claims in the Romance, and, in any case, the more enduring epitaph was to be the founding of the city of Alexandria where his legend would be developed.

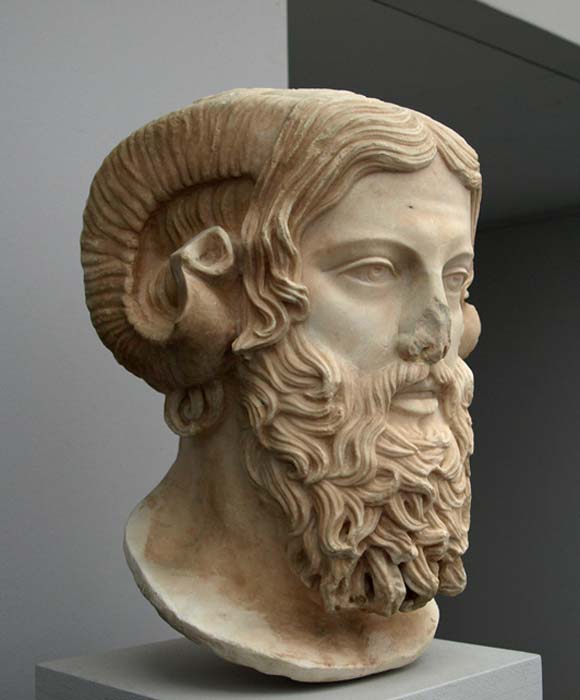

Zeus Ammon. Roman copy of a Greek original from the late 5th century BC. The Greeks of the lower Nile Delta and Cyrenaica combined features of supreme god Zeus with features of the Egyptian god Amun-Ra (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Genre Parallels

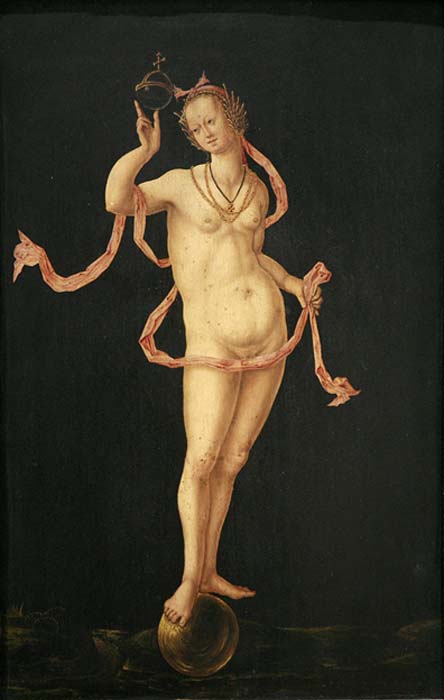

We have many examples of the genre offspring which were hugely influential in the Middle Ages and they were amongst the earliest texts translated into the vernacular literature that emerged in the Renaissance. Historia de Preliis Alexandri Magni (The Wars of Alexander the Great) of Archpriest Leo of Naples (10th century), first put to print in 1487, gave rise to a whole new generation of re-renderings of the story, as did the Alexandreis siva Gesta Alexandri Magni, a Latin poem in epic-style dactylic hexameter by the theologian Gautier de Chatillon (ca. 1135-post 1181), with much credit paid to the goddess Fortuna. The verses were so popular that they displaced the reading of ancient poets in grammar schools. Like the oil paintings of the period, they were cultural palimpsests, absorbing textual supplements and stylistic elements from other classical works as well as the iconography of their day.

Fortuna lightly balances the orb of sovereignty between thumb and finger in a Dutch painting of ca 1530. (Public Domain)

Through the romance genre, Alexander’s story finally infiltrated the East in a more permanent way than his own military conquest managed to. He entered the Qur’an texts, reemerging as Dhul-Qarnayn, the ‘two-horned’ who once again raised unbreachable gates to enclose the evil kingdoms of Yâgûg and Mâgûg at the world’s end; the reincarnation, with roots in the Syriac version of the Romance, had its earlier origins in the silver tetradrachms issued by Alexander’s successors that depicted him with rams’ horns. A Persian Romance variant was the Iskandernameh and alongside it Armenian and Ethiopian translations circulated imbuing the tale with their own cultural identities.

Armenian illuminated manuscript from XIVth century of Vth century translation. (Public Domain)

Many parallels to the Alexander romance corpus have appeared in literature: the rabbinic aggadah for example, with its folklore, historical anecdotes and moral exhortations dressed like biblical parables with attendant mythical creatures. We have the Norse Sagas which recapture a similar legendary past, and Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxon poem (ca. 1,000) of Scandinavian pagan legends and heroic exploits that emerged at the end of the Dark Ages when barbarism still triumphed over classical civilization However, the enduring tale of King Arthur perhaps has the most significance, and somewhat predictably, Alexander and Arthur crossed paths in the 14th century French romance, Perceforest.

Today in Greece the best-known Romance derivative is the He Phyllada tou Megalexantrou , first published in Venice in 1670 and never out of print through the three centuries that followed. The Phyllada portrayed Alexander as the protector of Greek Orthodox Christian culture, and ultimately as kosmokrator, the ruler of the world.

- Royal Bonds: How the Mother, Wife, and Daughter of Darius III Became Family of Alexander the Great

- Elephants, Peacocks, and Horses: The Amazing Animals of Alexander the Great

- The Time When Alexander the Great was ‘Defeated’

What made Alexander’s story so ripe for ‘romancing’?

The story of Julius Caesar, for example, paralleled with Alexander’s in Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, was conspicuously not ripe for a romance. Certainly, without the marvels developed by the fabulously inclined biographers on campaign with Alexander, a sober military treatise like Caesar’s war commentaries would not have provided sufficient flammable tinder either. “Legends and lies about Alexander were given currency by authors who had actually seen him or accompanied his expedition: there had been no Thucydides to strangle such monsters at birth” commented one scholar. And it was true. It required hagiographies and panegyrics to blow on the fire, and a death in distant Babylon, not on the steps of the Theatre of Pompey in a no-nonsense and fractious Rome. Strabo sensed it when he wrote of Alexander historians: “These toy with facts, both because of the glory of Alexander and because his expedition reached the ends of Asia, far away from us.”

Alexander on his deathbed. Hellenic Institute codex 5 f. 193v (Alexander Romance recension gamma) (14th century). (Public Domain)

But there was probably no single reason or influence that gave the book its birth, and there would have been a number of ‘pre-texts’ behind the first edition. But if the kaleidoscope of colorful protomatter behind the Greek Alexander Romance coalesced into focus for a moment, we would likely see Callisthenes’ Deeds of Alexander with its apotheotic spice, the encomium on education replete with the quasi-utopian land of Musicanus and Brahmin sophistry from the campaign historian and Cynic philosopher Onesicritus, with scrolls of the court usher Chares and Polycleitus of Larissa, and even Ctesias, physician to Artaxerxes II, in the melting-pot beside them. Much of their writing and tales had already been synthesized by Cleitarchus into an early colorful account that laid the foundations of the quasi-historical texts that added in drama and exaggeration. Toss in the epistolary corpus to and from Alexander that Plutarch believed was genuine for extra biographical seasoning, and then simmer with the Indian wonders of the general and naval officer, Nearchus, before baking it in the ovens of the philosophical schools of the Cynics and the Stoics. We might further season it with the On Fortune of the exiled peripatetic philosopher Demetrius of Phalerum, for it linked God, man, and the mercurial nature of divine intervention.

The most influential element was Egypt; The Demotic Chronicle, The Dream of Nectanebo and Romance of Sesonchosis (Alexander is supposed to have declared himself the ‘new Sesonchosis’), and many more of the themes that were regurgitated in the Romance originated here. The Nectanebo cycle and the Alexandrian Lists were each Egyptian condiments ground in, and the result, a rich new Hellenistic recipe for the Macedonian king, was now not about who Alexander had been, but what Alexander now meant to a world in flux.

As the British historian TB Macaulay neatly put it: ‘History commenced among the modern nations of Europe, as it had commenced among the Greeks, in romance. Truth and romance make unlikely bedfellows, and yet in Alexander’s story, they never slept apart.”

This article is an extract from the book ‘In Search of the Lost Testament of Alexander the Great ’ by author and historian David Grant.

--

Top Image: Detail; Byzantine Alexander Romance, Venice, 14th century. (Public Domain)

By David Grant

Updated on November 4, 2021.