Fiji’s Rampant Cannibalism for 2,500 Years Earned it the Name ‘Cannibal Isle’

Fiji, the idyllic paradise in the South Pacific, carries a dark historical secret. Long before it was renowned for its scenic beauty, early European explorers knew it as the foreboding 'Cannibal Isles'. Such a reputation served as a severe deterrent to European settlement, with the practice of cannibalism being deeply entrenched in Fijian history.

An Elaborate, Ritualized Affair

The victims, whether dead or alive, destined for such gruesome ceremonies were termed ‘Bokola’. This wasn’t a casual affair; rituals were elaborate, underscored with sadistic overtones. If the victim, the Bokola, was still alive, the continuous beating of the Lali drum filled the air. Simultaneously, men enacted the Cibi death dance, reminiscent of the pre-game performance of the Fiji rugby team. Women, on the other hand, celebrated the victorious warriors and their unfortunate captives with the provocative Wate or Dele dances, often culminating in the harrowing sexual abuse of the captured Bokola.

This grisly tradition, archaeological records suggest, was not a mere legend. Evidence of cannibalism in Fiji dates back 2,500 years. Butchered human bones, conspicuously mingled with food waste, were a common find until the mid-19th century. By 1800, the act had transcended mere consumption; it had become ritualistic, woven into the fabric of Fijian religion and warfare. Cannibalism wasn't an act of sustenance, but rather a deliberate act of vengeance in a society deeply rooted in ancestor worship.

- Ancient And Modern Cannibalism: A Question of Taste

- Our Ancestors Were Cannibals – and Probably Not Because They Needed the Calories

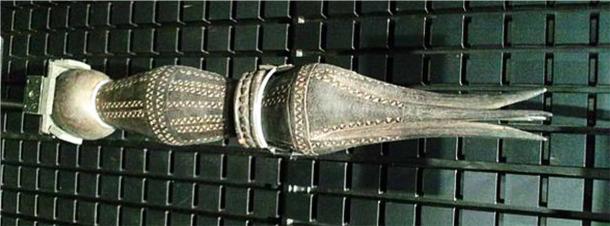

A cannibal fork used by a Fijian chief at cannibal feasts. (Yanajin33 / CC by SA 3.0)

Fijian Cannibalism Was a Grisly Practice

While enemies slain in warfare were the most common sources, other demographics, like conquered people or slaves, also met this grisly end. Such rituals often accompanied significant events, such as temple constructions or chief installations. Paramount chiefs even employed assassins to ambush and provide them with fresh Bokolas.

In these intense ceremonies, the bete (priest) would present the bodies to the war gods. Victims were dragged to the bure kalou, the temple, with fervor. In chaotic scenes, men and women performed their death dances. The bete, using a bamboo knife, would dissect and prepare the bodies for cooking. Following consumption, famous enemies had their skulls turned into yaqona cups, while their shin bones were crafted into sail needles. This ritualistic consumption signified the complete annihilation of the victim, both in body and spirit.

The last known incident of this macabre tradition occurred in 1867 when Methodist missionary Reverend Thomas Baker and six Fijian student teachers met their tragic fate. It is believed they were executed upon the orders of a chief who resisted the growing influence of Christianity and the abandonment of traditional Fijian beliefs.

Today, Fiji does not hide from this dark chapter of its history. One can buy coconut-shell made cannibal dolls or wooden cannibal forks from souvenir shops. Tours to the Naihehe Cave, home to the last-known cannibal tribe, offer a chilling window into the past. While Fiji has moved far from its cannibalistic past, its shadows remain, preserved and remembered.

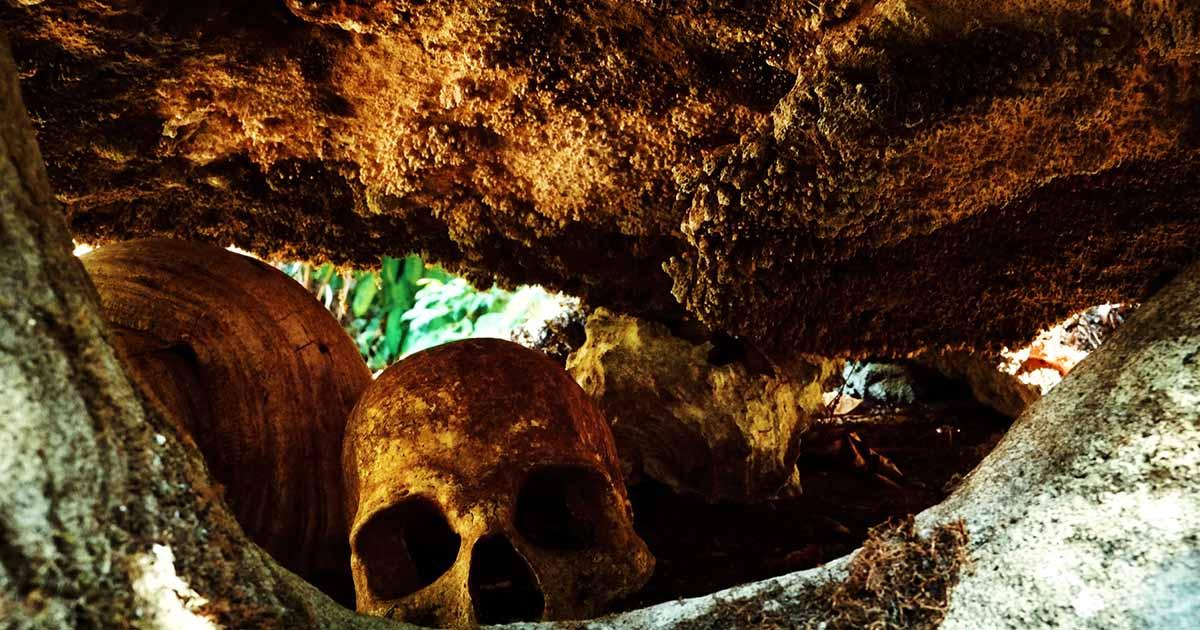

Top image: Human remains of bones and skulls at a traditional cannibal site. Source: simanlaci / Adobe Stock.