What Was an Ancient Chinese Palace Doing in the Enemy Territory of Siberia?

Located in the majestic Altai-Sayan Mountains in the south of Siberia, the city of Abakan has a long and rich history going back thousands of years. But in the 1940s, archaeologists found something near Abakan, that was entirely unexpected – the 2,000-year-old remains of a Chinese palace typical of the Han Dynasty in China. What was so unusual about this discovery was the fact that not only was the palace hundreds of miles away from the region of the Han Empire, it was also located in territory that belonged to their arch-enemy, the Xiongnu.

Discovery of the Han Empire Palace in Khakassia

The Xiongnu were a nomadic pastoral people who formed a great tribal league that came to dominate much of Central Asia from the 3 rd century BC until the 2 nd century AD. The Xiongnu were a constant threat to China’s northern borders. In fact, it was their repeated invasions that prompted the small kingdoms of North China to begin erecting barriers, in what later became the Great Wall of China.

- King Carved In Stone Found at 4,200-Year-Old Chinese Pyramid Palace

- Closer to Enlightenment? Potala Palace, the Highest in the World

The Xiongnu civilization and the Han Empire frequently clashed in military conflicts. (Erica Guilane-Nachez/Adobe Stock)

The discovery of the palace was first made in 1941 when Russian construction workers were clearing a track from Abakan, the capital city of Russia’s Khakassia Republic, to the village of Askyz, and found the buried foundations of a ruined building. When the site was excavated by archaeologists over the following four years, they found something highly unusual – the remains of a large palace typical of the Han Empire (206 BC – 220 AD).

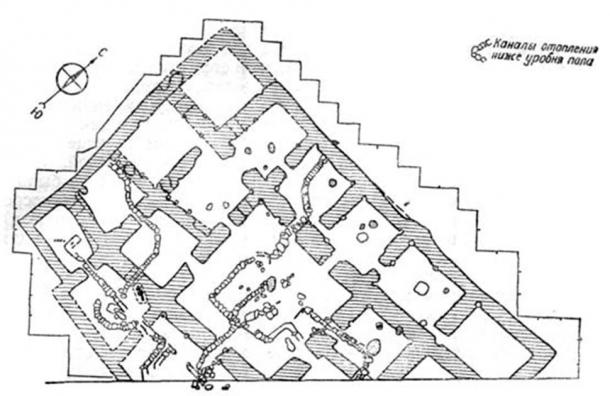

The building was found to be oriented precisely to the cardinal directions from East to West. Its length was 45 meters (148 ft) from north to south and its width, 35 meters (115 ft). In the center of the palace was a large square room, 12 by 12 meters (39 by 39 ft).

The palace consisted of twenty rooms and one hall. The floor and walls of the palace were made of mud. In the central part, the walls reached up to 2.2 meters (7.2 ft) in thickness, while the walls of the side chambers were somewhat thinner. Another feature of the building was the heating system located under the floor of the rooms. This whole system of branched channels made from stone slabs allowed heat to be distributed throughout the palace via the hot air from the furnace.

A sketch showing the layout of the palace in Abakan. (GB Shchukin)

Artifacts Unearthed: From Jade Vases to Construction Tools

Archaeologists found the remains of many Chinese style roof tiles, some of which bore inscriptions typical of the era of the Han Dynasty. On all these tiles was written the same text: "Son of Heaven (the Chinese emperor), 10,000 years of peace, and one of which (i.e. the empress), we wish 1,000 autumns of joy without sorrow."

The doors of the central hall were decorated with massive bronze cast mascarons in the form of a sculpted face, with handles in the form of horned rams. The ringed handle passed through the nose of the ram.

The mascaron doorknob. Exhibited in Khakassia Abakan Museum, BC in the 1st century, 3 separate door knockers made in the form of Hun Turkic nomadic tribe. (Exhibited in Khakassia Abakan Museum, BC in the 1st century, 3 separate door knockers made in the form of Hun (Turkic nomadic tribe) Erlik Han., /CC BY-SA 4.0)

Among the other excavated artifacts at the palace, archaeologists found jade vase fragments, gold earrings, bronze ware, pottery, knives, belt buckles, plow lines, stone carvings of elephants and animal heads, and a range of tools that would have been used in its construction. It is unclear where these artifacts are now located.

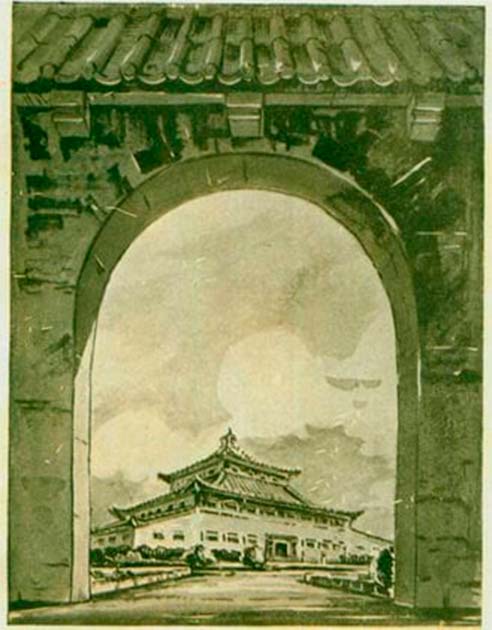

Architectural impression of the Chinese palace near Abakan. (GB Shchukin)

The discovery of the palace sparked a lively debate regarding how the palace and its high-ranking occupants came to live not only far away from the Han homeland, but also in enemy territory.

Russian scholars like S V Kiselev and L R Kyzlasov have proposed that the palace belonged to ancient Chinese General Li Ling, who had been defeated by the Xiongnu and possibly defected to them as a result. Li Ling had led a force of 30,000 Han warriors against Xiongnu raiders in 99 BC, leading to the complete decimation of his army. Only 400 of Li Ling’s troops made it back alive to Han territory.

It was initially believed that Li Ling had died on the battlefield, which would have been the most noble end for a defeated general. However, it was later discovered that Li Ling had surrendered to the Xiongnu, and rumor quickly spread that he was a traitor and had defected, although there is little evidence to support this claim.

When news reached the ruler of the Han Dynasty, Emperor Wu, he ordered the Li family to be severely punished. The theory goes that news of the harsh treatment of his family reached an imprisoned Li Ling, who then did defect and, in an act of revenge against the Emperor, began training Xiongnu warriors in Han battle techniques. Presumably, Li Ling was eventually accepted by the Xiongnu, allowing him to construct his palace in their territory.

- The Perfectly Preserved Yuka Wooly Mammoth Mummy (Video)

- 3,000-Year-Old Grave of Charioteer Could Rewrite Siberian History

The Mystery of the Chinese Palace: An Unresolved Historical Debate

While this opinion has remained popular, other views have been expressed as well. More recently, for example, it was claimed by A. A. Kovalyov, that the palace was the residence of Lu Fang, a Han throne pretender from the Guangwu era in the first century AD. According to records, Lu Fang claimed he was a descendant of a Han Emperor and fought to become legal Emperor of China. However, he later raised a revolt and defected to Xiongnu. According to the Hou Han Shu, the official records of the Later Han Dynasty compiled by Fan Ye (5 AD), he lived with his family in Xiongnu for ten years until his death. This theory is supported by Chinese scholar Chen Zhi, who claims a character used in the tile inscriptions can be dated to the period 9 – 23 AD, much too late to have been Li Ling.

While both theories are plausible, the fact remains that scholars still cannot say within any certainty, who the Chinese palace belonged to, and what it was doing in the land of the Xiongnu.

Top image: In the Altai-Sayan Mountains in Siberia, the owner of the Chinese Palace has remained a mystery. Source: henvryfo/Adobe Stock

References

Baidu. Abakan Palace Ruins. Available at: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%98%BF%E5%B7%B4%E5%9D%8E%E5%AE%AB%E6%AE%BF%E9%81%97%E5%9D%80?fromtitle=Ruined%20Palace%20at%20Abakan%20City&fromid=10357308&type=syn

Evtyujov, LA. Southern Siberia in antiquity: The footsteps of ancient cultures, from the Volga to the Pacific Ocean. Available at: http://kronk.spb.ru/library/evtuhova-la-1954.htm

Kovalyov, A. A. 2007. Chinese Emperor on the Yenisy? Once Again About the Owner of the Tashebik "Palace”. The Ethnohistory and Archaeology of Northern Eurasia: Theory, Methods, and Practice] (in Russian). Irkutsk, Russian. pp. 145–148

Perry, D. 2017. How Did An Ancient Chinese Palace End Up In Siberia? Available at: https://www.chinatopix.com/articles/7165/20140818/ancient-chinese-palace...

Unknown. Abakan. Available at: Princeton.edu

Unknown. 2023. Xiongnu. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Xiongnu