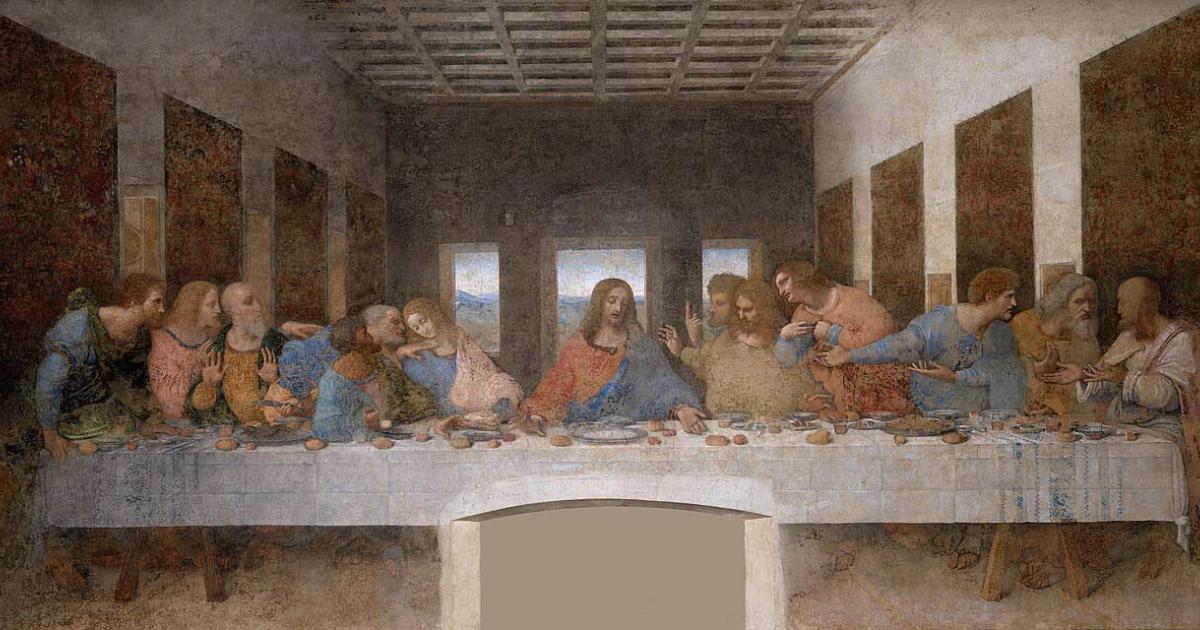

For over five centuries, Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper has been interpreted as a dramatic moment frozen in time. The instant when Jesus announces that one of his disciples will betray him. Judas Iscariot, traditionally identified as the villain of Christian history, has been cast as the central antagonist in this sacred drama.

But what if we've been reading the masterpiece wrong all along? What if Leonardo, one of the most brilliant minds of the Renaissance, encoded an entirely different story within the gestures, gazes, and spatial arrangements of his monumental fresco?

Recent iconographic analysis suggests that The Last Supper may not illustrate the canonical gospels at all. Instead, the painting appears to dramatize passages from the Gnostic gospels discovered in Egypt, particularly those attributed to Mary Magdalene and Philip. These ancient texts, suppressed by early Church authorities and rediscovered in 1945 near Nag Hammadi, present a radically different version of early Christianity: one centered on inner spiritual knowledge (gnosis) and the pivotal role of Mary Magdalene as the primary recipient of Christ's secret teachings.

This alternative reading transforms our understanding of Leonardo's work from a simple biblical scene into a bold visual denunciation—a coded message about the suppression of spiritual wisdom and the rise of institutional dogma.

The Nag Hammadi Discovery: Voices from the Margins

To understand this reinterpretation, we must first journey to 1945 Egypt, where a collection of ancient manuscripts was unearthed near the town of Nag Hammadi. These codices, dating from the third and fourth centuries AD, contained texts that had been branded heretical and systematically suppressed by early Church authorities. Among them were the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and other writings that offered alternative visions of Christ's teachings. Visions that emphasized personal enlightenment over institutional authority.