Unlocking the Secrets of the Oldest Map of Maritime Asian Trade Routes Provides Unexpected Results

Secrets of the world’s oldest surviving map of maritime trade routes in Asia are being revealed with a range of modern imaging techniques and other research. Dating back to the early 17th century, the Selden map has a lot to teach scholars about globalization not long after Europeans first landed in Asia in 1497.

Unlike the Portuguese captain Vasco da Gama, who was appointed to find a sea route from Europe to India in 1497, this map shows ancient maritime routes from the Far East to India. The merchant map has been restored and analyzed to reveal the materials it was made of and how accurate the routes were. The researchers have also developed a new theory about where the map was made.

The Selden map (before the 2011 conservation treatment) with the trade routes enhanced by thick black lines. (The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

Speculation about the origin and author of the map have been debated since it was rediscovered in 2008 in Bodleian Library of England’s Oxford University, where it arrived in 1659 as a gift of John Selden, a high-profile lawyer in London at the time.

- Ancient Maps spark debate between China and Philippines over South China Sea islands

- The Buache Map: A Controversial Map That Shows Antarctica Without Ice

- Hereford Mappa Mundi: Legendary Cities, Monstrous Races, and Curious Beasts in a Single World Map

The map measures 1.6 by 1 meter (5.25 by 3.28 feet). The experts who examined the map published the findings of their rigorous analysis and examination in the journal Heritage Science. The lead researcher was Sotria Kogou of the School of Science & Technology at Nottingham Trent University.

The team believes it was made somewhere around 1607 to 1619. The cartographer inked in sea trade routes of ancient Asia and then painted the land and ports.

These details before the 2011 restoration of the map show trade routes in Vietnam and Cambodia that were later covered by land. The smaller image, b, shows Bali on Java. (Kogou et al.)

“It is a unique example of Chinese merchant cartography, showing a network of shipping routes with compass directions starting from the port of Quanzhou, Fujian province, and reaching as far as Japan and India,” says an article about the new analysis and restoration of the map on Phys.org.

Little is known definitively about where the map was made and who made it. But with spectral imaging technologies, researchers are starting to unravel some secrets and have a theory about where it was produced. The person who drew the map used a binding of gum Arabic—a binding material common to south and west Asia and Europe and different from the animal glue that was typically used in Chinese documents.

- Brush strokes on very ancient murals may rewrite the history of art in China

- Zheng He: Famous Chinese Explorer Who Added Wealth and Power to the Ming Dynasty

- 1,700-year-old Silk Road cemetery contains carvings of the four mythological symbols of China

The article in Heritage Science states the researchers can’t rule out any of the various hypotheses about the map’s origin, but:

… the South and West Asian influence as shown in the binding medium and pigment use makes a location towards the more western ports on the map with strong Islamic influence more likely. Finally we propose an alternative origin for the map in Aceh at the north-west end of Sumatra where it opens out to the Indian Ocean. It is the most westerly port in South East Asia marked on the map and it has the longest history of the presence of Islam in South East Asia as well as a long history of Chinese contact.

Aceh is one of six ports marked with a red circle on this map.

17th century Selden Map of China. (Public Domain)

The authors lament that there aren’t more surviving maps and other types of manuscripts from Southeast Asia of that era to compare to the materials, pigments, and colors used in this map. The author applied paints of red, copper green, yellow, and indigo (blue) to the map after the routes were drawn.

The cartographer made a number of mistakes and altered the map later, apparently taking into account more recent and precise information about trade routes. Most of the trade routes were drawn accurately, but a number of them were off kilter and drawn after the coasts were painted.

The researchers also say he clearly did not plan the entire map from the beginning, but rather redrew some routes several times, which is why he ran out of space toward the western and southern areas.

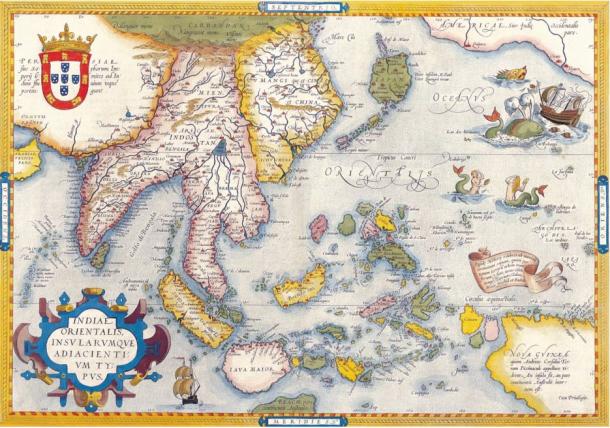

Mercator map of “India Orientalis”, Amsterdam 1619.This redrawn map is contemporaneous with the Selden map. The map was made for medieval Portuguese trade in the Far East. (Kiến Trúc Việt-Vietnam Architecture)

The researchers say much more research needs to be done on the map to discover all its secrets. While the map uses some Chinese writing characters, the authors wrote in their report: “Finally, many unorthodox Chinese characters have been used on the map and a systematic study of the use of these characters may also shed light on the cartographer’s background.”

One of the researchers, Professor Haida Lang, head of the Imaging & Sensing for Archaeology, Art History & Conservation research group at Nottingham Trent University, told Phys.org:

A seemingly Chinese map has turned out to be the material evidence of a fusion of cultures. It is stylistically a Chinese painting that follows some Chinese and non-Chinese cartographic elements, but the painting materials and their usage are more akin to those of Persian or Indo-Persian manuscripts. Because of its geographic location, Aceh was frequented by Indian, Arab, Chinese and European traders. We believe the map could have been made there by a Fujianese, possibly a Muslim in close contact with the Islamic world.

Spectral imaging of the Selden map using PRISMS at the Bodleian Library. (Kogou et al.)

Top image: The early 17th century Selden map held at Oxford University is yielding priceless historical information, but much more study and imaging analysis need to be done to unlock all of its secrets. Source: Kogou et al.

By Mark Miller