Dire Consequences of Suicide in the European Middle Ages

The cycle of life and death is an eternal and unchanging truth of human history. Yet, the attitudes around both are influenced and shaped by a number of factors. Today, dying of old age is seen as a graceful extension of the natural cycle of life and death, but dying early, either through suicide or euthanasia, has a different set of attitudes attached to it. Modern attitudes about suicide actually emerged from medieval socio-cultural and religious beliefs. Suicide, or self-murder, was only mentioned in official records at the turn of the millennium, from 1000 AD onwards.

Today, the conversation around suicide has acquired greater degrees of empathy, as seen through the prism of psycho-social and mental wellbeing (particularly, the absence of it). Yet, Australian religious scholar Professor Carole M. Cusack’s research indicates that it was religion that controlled this “medieval” attitude towards suicide. Criminal justice systems, even secular ones, were influenced by theology, and followed soon thereafter in medieval Europe.

In the view of the Christian church, suicide was a sin and usually the sinner and his family were punished. And no self-murder victim was allowed to be buried with other good Christian souls in a cemetery. (PeskyMonkey / Adobe Stock)

Christianity And Its Views On Suicide As A Sin

Christian morality and the role of Judas are heavily intertwined with the development of the idea of suicide as sin. According to all the four canonical gospels, Judas Iscariot was one of the 12 disciples of Jesus Christ. Judas’ betrayal ultimately started the chain of events leading to Jesus’ crucifixion.

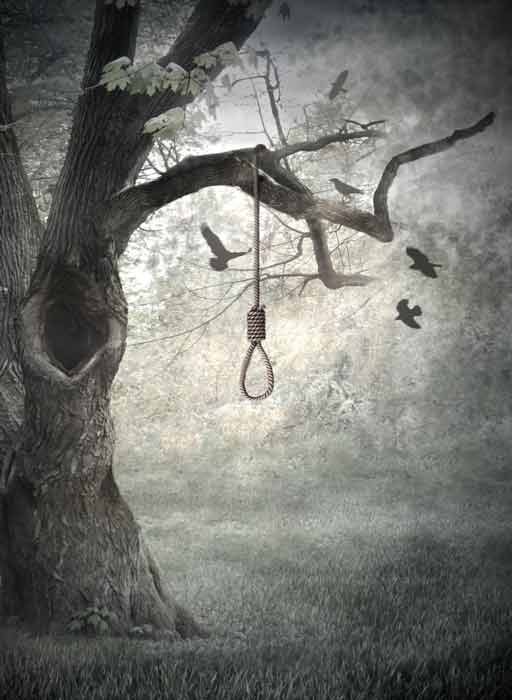

To prevent the crucifixion, Judas attempted to return the money he had taken to reveal Jesus’ identity. Failure to do so pushed him into committing suicide by hanging. Over time, Judas’ name began being associated with betrayal and backstabbing, with as much disgust as Brutus’ betrayal of Caesar.

- Staked Through the Heart and Buried at the Crossroads – The Profane Burial of Suicides

- Petitioning for Death: Did Ancient Romans Really Ask for Permission to Commit Suicide?

One of the earliest documented views on suicide in Christianity are those by Augustine of Hippo, in the City of God (413-426 AD). His interpretation of the Sixth Commandment “Thou shalt not kill” was seen to encompass the self. He saw it as a “detestable and damnable wickedness,” equating it with murder. Even in a situation where a Christian feared for their life in getting corrupted, or raped, Augustine thought it to be unthinkable to consider suicide as an option.

He went as far as condemning the views of earlier Roman philosophers and statesmen, like Cato, Seneca and Lucan who preached the noble virtuosity of suicide under exceptional circumstances. In the vast depths of Christian theological history, Augustine became the first to conflate suicide with sin. Juridically, the persecution of those who commit suicide came in the 6 th century AD onwards, the second century of the so-called Dark Ages or Middle Ages.

Medieval “feudal” justice, beginning in the 10th century AD, was severe on suicides. And the ramifications of property ownership in the case of serfs who killed themselves was imposed. (cranach / Adobe Stock)

Suicide and Medieval Justice

Between the 10 th and 12 th centuries in many parts of Europe, self-murder became a felony crime. Pre-industrial Europe, prior to becoming a vast imperial power, was not just under the influence of the Church, but also, feudalism. The propertied nature of the “Lord” and “Serf” relationship meant that the master saw a peasant’s suicide as a denial of his possession. Confiscation of the serf’s goods was seen as a legitimate action of claiming what was anyway “the Lord’s property.”

The confiscation of land and property, either by the overlord or the monarch, only increased statist power. With an increase in authoritarian control, punishment became harsher. In England, the “Customs of Anju and Maine” of 1411, equated suicide with rape and murder. In France, in the same period, laws called for the house of the suicide victim to be torn down and the sinner’s family to be banished. The victim’s body, if male, was to be hanged again in the gallows, and then burnt. Even “post-mortem torture” was seen as a legitimate form of punishing suicide, particularly by invoking the fear of self-murder into the living.

Suicide was also connected with bad luck, superstition, and older folkloric views across medieval Europe until the 20th century, and even today. (Édouard Manet / Public domain)

Punishment of Suicide in the Afterlife

Those who committed suicide became the subject of gossip and folklore, often accused of upsetting the balance of order in nature. In Switzerland, for example, a bout of bad weather was blamed on the burial of a woman in town who’d committed suicide. Punishment of suicide in the afterlife was enshrined in the law too. For example, in England, in 740 AD, the Archbishop of York drew up legislation ordering priests to not give Christian burials to those who’d died by suicide.

- The Honorable Death: Samurai and Seppuku in Feudal Japan

- The Aokigahara Forest of Japan: Many Enter, But Few Walk Out Alive

Such laws only enhanced stigma and myth, made at the cost of the deceased, and the living family members. To protect their families from social exile, figuratively, family members would often try to influence the coroner’s report in suicide cases. If that failed, attempts were made to hide some of their possessions, so that these were protected from the state.

In situations where a married male committed suicide, this was often the case, the widow would be left nothing by the state. In many other cases, in a bid to hush-up the matter, family members would attempt to bury the deceased themselves.

Top image: The idea of suicide is complicated and controversial, and the position of the Church was less than sympathetic. Source: kharchenkoirina / Adobe Stock.

By Rudra Bhushan

References

Cusack, C. M.,2018. Self-Murder, Sin and Crime. Journal of Sin and Violence, Volume 6. Philosophy Documentation Center.

Gershon, L. 2021. Why Suicide Was a Sin in Medieval Europe. Available at: https://daily.jstor.org/why-suicide-was-a-sin-in-medieval-europe/

Murray, A. 1998. Suicide in the Middle Ages, Volume I. Oxford University Press.

Seabourne, A., Seabourne G., 2001. Suicide or accident – Self-killing in Medieval England, Series of 198 cases from the Eyre records. The British Journal of Psychiatry, Volume 178.

Battin, M.P., 2015. Augustine (354-430). Available at: https://ethicsofsuicide.lib.utah.edu/selections/augustine/