Mongolian Giant Camels and Hominins Coexisted 27,000 Years Ago

A new report by an international team of researchers in the journal Frontiers in Earth Science has shown that the last of Mongolian giant camels may have coexisted with the much smaller wild Bactrian camel (Camel ferus) and ancient hominins until 27,000 years ago. And by ancient hominins the study suggests Homo sapiens and maybe also Neanderthals and Denisovans. According to the study, the extinct Camelus knoblochi, a shaggy giant camel with two humps, is “related” to the modern Bactrian camels, which includes its wild version (Camelus ferus) and the domesticated version (Camelus bactrianus). Mongolia was likely the last home of this giant camel before it went extinct, according to the study.

Co-author Dr John W. Olsen said, as reported in the Frontiers blog:

“C. knoblochi fossil remains from Tsagaan Agui Cave [in the Gobi Altai Mountains of southwestern Mongolia], which also contains a rich, stratified sequence of human Paleolithic cultural material, suggest that archaic people coexisted and interacted there with C. knoblochi and elsewhere, contemporaneously, with the wild Bactrian camel.”

Throughout the arid belts of Eurasia and Africa, camelids (dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas and guanacos) were crucial to human existence not only because of their transportation abilities but also the resources they provided in the form of milk, meat, leather, wool, bones, and dung.

However, the interaction between hominins and Bactrian camels in prehistoric contexts is, for good reason, not well understood. However, the latest study does shed some light on how the giant camels and hominins likely co-existed and why the giant beasts went extinct.

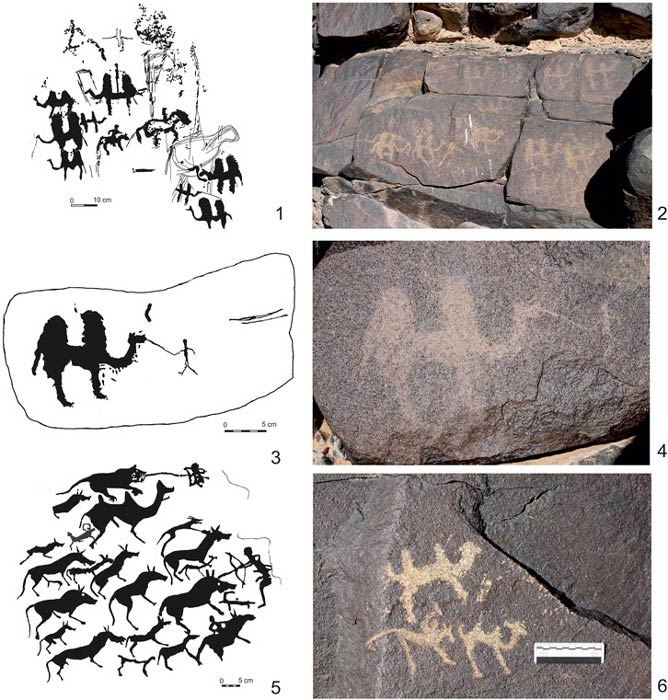

Bronze Age camel petroglyphs in the Mongolian Gobi Desert, where evidence of the giant camel has also been found. (Frontiers in Earth Science)

Giant Camels Were Huge But Are Still Poorly Understood

Nearly 3 meters (9.8 feet) tall and weighing more than a metric ton (2,200 pounds), C. knoblochi would have been a veritable giant compared to the wild Bactrian camels it co-existed with. The exact taxonomic relationship between the two species and other extinct giant camel species is not well understood.

- First humans in Florida lived alongside giant animals

- Spectacular photographs shed light on the ancient nomadic lifestyle of Mongolia

According to the Frontiers blog article, the immense size of these giant camels didn’t seem to be a long-term advantage compared with the smaller Bactrian camels. Mongolia is still home to the last two wild populations of C. ferus, which are critically endangered.

The new study analyzed five C. knoblochi leg and foot bones found in Tsagaan Agui Cave in Mongolia in 2021, and one from Tugrug Shireet in the Gobi Desert of southern Mongolia. They were found alongside the bones of wolves, cave hyenas, rhinoceroses, horses, wild donkeys, ibexes, wild sheep and Mongolian gazelles. This assortment suggests that the giant Bactrian lived in a steppe habitat, both mountainous and lowland, rather than the desert environment of its modern relatives.

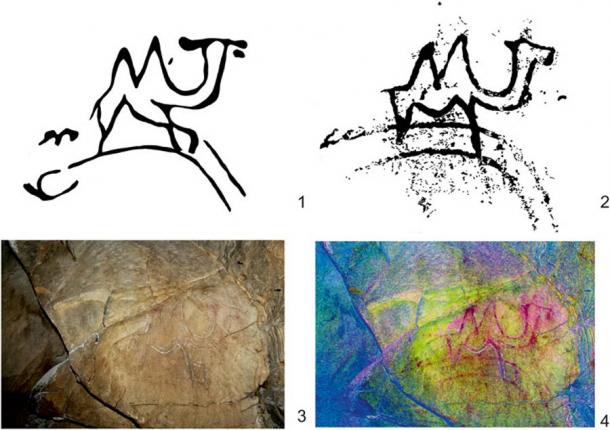

A purported Paleolithic image of a “giant camel” in the Khoid Tsenkheriin Agui Cave, where the bones of the extinct giant camel species were also found. (Frontiers in Earth Science)

The Giant Camel Loses the Battle for Survival

What pushed the giant camel to extinction? The primary reason appears to have been climate change, according to the authors of the study. “Here we show that the extinct camel Camelus knoblochi persisted in Mongolia until climatic and environmental changes nudged it into extinction about 27,000 years ago,” the Frontiers blog reports Olsen as saying.

In the late Pleistocene era, Mongolia transitioned from steppe to dry steppe and then desert. In the new climate conditions, C. knoblochi’s size made it harder to survive as food and water sources changed and shrank. Its smaller cousins obviously fared better.

“Apparently, C. knoblochi was poorly adapted to desert biomes, primarily because such landscapes could not support such large animals, but perhaps there were other reasons as well, related to the availability of fresh water and the ability of camels to store water within the body, poorly adapted mechanisms of thermoregulation, and competition from other members of the faunal community occupying the same trophic niche,” the authors wrote.

According to the study authors the giant camels may have been pushed for a while into the steppes of neighboring Siberia. But here too survival would have been precarious.

Apart from climate change, hunting and scavenging by humans could also have hastened the giant camel’s extinction. Evidence for this comes in the form of a giant camel metacarpal bone from Tsagaan Agui Cave, dated to between 59,000 and 44,000 years ago, that shows traces of both butchery by humans and hyenas gnawing on it.

“We don’t yet have sufficient material evidence regarding the interaction between humans and C. ferus in the Late Pleistocene, but it likely did not differ from human relationships with C. knoblochi—as prey, but not a target for domestication,” the Frontiers blog reported.

- First Giant Bird Found In Europe Lived Alongside Early Humans

- Unique Painting of Extinct Giant Sloth Discovered in Madagascar Cave

But while hunting by humans and inter-species competition could have added to the pressure on Mongolia’s giant camels, the inability to adapt to a changing climate resulted in its extinction.

According to the Frontiers blog, lead author Dr. Alexey Klementiev said, “We conclude that C. knoblochi became extinct in Mongolia and in Asia, generally, by the end of Marine Isotope Stage 3 (roughly 27,000 years ago) as a result of climate changes that provoked degradation of the steppe ecosystem and intensified the process of aridification.”

Top image: This fat and shaggy Bactrian camel in a mountain landscape more or less captures the image of the extinct giant camel.Source: ilyaska / Adobe Stock

By Sahir Pandey

References

Dijkstra, M. 2022. Last of the giant camels and archaic humans lived together in Mongolia until 27,000 years ago. https://blog.frontiersin.org/2022/03/25/frontiers-earth-science-camelus-knoblochi-giant-camel-last-refuge-pleistocene-mongolia/

Klementiev, Alexey M. et al. 2022. First Documented Camelus knoblochi Nehring (1901) and Fossil Camelus ferus Przewalski (1878) From Late Pleistocene Archaeological Contexts in Mongolia. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2022.861163/full

Phys.org. 2022. Last of the giant camels and archaic humans lived together in Mongolia until 27,000 years ago. Available at: https://phys.org/news/2022-03-giant-camels-archaic-humans-mongolia.html