New Birthing Girdle Study Answers Questions About Medieval Childbirth

In the Middle Ages, pregnant women allegedly wore a type of specially prepared wrap known as a birthing girdle. Birthing girdles were long, thin, rolls made from animal skin parchment. They were imprinted with religious symbols and iconic imagery, and inscribed with prayers to Christ, the Virgin Mary, and various saints associated with childbirth and motherhood.

These girdles had no obvious medical function. But they were believed to possess the power to protect the health of both mother and child throughout pregnancy, and perhaps even during the birthing process.

How Modern-day Scientists Examined One Birthing Girdle

In order to learn more about this practice, a team of scientists led by Sarah Fiddyment, a postdoctoral researcher from the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge, performed a deep chemical analysis on a girdle identified as Manuscript 632, which has been preserved in England for more than 500 years.

- Ancient DNA on parchments reveal hidden stories

- Bizarre Methods of Baby Detection: A Short History of the Pregnancy Test

“Although these birth girdles are thought to have been used during pregnancy and childbirth, there has been no direct evidence that they were actually worn,” Fiddyment pointed out. “This girdle is especially interesting as it has visual evidence of having been used and worn, as some of the images and writing have been worn away through use and it has many stains and blemishes."

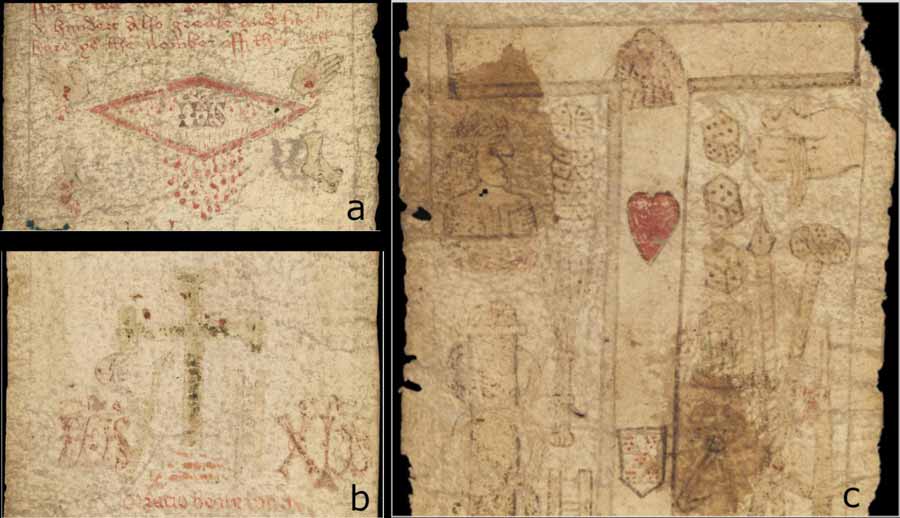

MS. 632 birthing girdle section showing a cross with a red heart and shield. (Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection)

Fiddyment has expertise in the area of protein detection and analysis. For this experiment, she used a special testing procedure to remove samplings of minute traces of proteins that were still embedded in the sheepskin parchment used to make this particular birthing girdle.

What she and her colleagues discovered was most enlightening.

“We have been able to detect a large number of human proteins matching cervical-vaginal fluid, which would indicate active use of the girdle in pregnancy/childbirth,” she said in a press release announcing her team’s findings. "In addition, we detected numerous non-human proteins including honey, milk and plants which have all been documented in medieval texts as treatments relating to pregnancy and childbirth, reinforcing our evidence of active use of this particular birth girdle."

"The fact that we have been able to detect these specific additional non-human proteins further reinforces the evidence that this girdle was actively used in late pregnancy and childbirth,” said Fiddyment. “It also gives supporting evidence that these documented treatments were actually used."

Whether these girdles had any actual protective power or not it is clear that the women who used them truly believed in their effectiveness. These long parchment wraps essentially functioned as protective talismans, which could help secure good outcomes for mothers and newborns (at a time when such an outcome was far from assured).

The recent birthing girdle study focused on the medieval English birth scroll known as MS.632 (c. 1500), which is part of the Wellcome Collection, London. The girdle contains prayers and invocations for safe delivery in childbirth. Biomolecular evidence found on the girdle proved that it was actively used. (Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection)

The Manuscript 632 Birthing Girdle: Origin and History

During medieval times, giving birth was the leading cause of death for women. Infant mortality rates were also high, reflecting the lack of high-quality medical care that was available at that time.

As a guard against these perils, monks often distributed birthing girdles to parishioners who were expecting children. These were sacred items, and they were reserved for a very important purpose.

The birthing girdle known as Manuscript 632 was believed to have been made sometime in the early 16 th century. The girdle contains two inscriptions on the back, which explain its form and function.

The first inscription claims that the length of the parchment is proportionate to the height of the Virgin Mary. The second inscription relates an (obviously mythical) origin story that tells how the parchment came into the possession of a certain Pope Leo (there had already been nine Pope Leos at the time the girdle first appeared, so it isn’t clear which one this story refers to).

According to this story, the birth girdle was delivered to the pope in a golden coffer by an angel. On its front side, the long parchment contained prayers to Christ and the Virgin Mary, plus a vivid pictorial representation of Christ’s crucifixion, all of which had supposedly been drawn and composed in heaven before the girdle was passed on to the pope.

By carrying the parchment and regularly saying the prayers it featured, the person in possession of it would be protected from pestilence, thievery, death in battle, accidental death or death caused by natural disaster, and encounters with the devil himself. If carried by a pregnant woman (as it most commonly was), the power of the parchment would ensure that the child would be delivered safely and that both mother and child would survive the perilous journey of childbirth.

Medieval image of childbirth, 15 th century. (Public Domain)

The inscription explained how essential it was that a woman giving birth survive long enough so that she could go through a process of purification, which would release her from the state of sin associated with childbirth. A purification ceremony would take place in the church approximately 40 days after a woman gave birth, and church doctrine at the time claimed that if a woman died without being purified her soul would be condemned to eternal damnation.

With the Reformation just around the corner, the type of worship embodied by birthing girdles was on the verge of going out of style. Belief in the protective power of talismans was increasingly viewed with embarrassment by religious reformers within the Catholic Church and without, and these guardians of the faith eventually set out to collect and destroy any and all items that might remind the pious of the Church’s past flirtations with superstition.

- Long Before Face Masks, Islamic Healers Tried to Ward Off Disease With Talismans

- Rings, Gestures, and Phallus Talismans: The Evil Eye and Ancient Ways to Ward Off Its Power

I.H.S. monogram in red within a flattened diamond-shaped figure; at the corners, the Five Wounds and the Blood: in red and black. (Wellcome Collection)

Birthing girdles were among the items targeted for destruction, which is why only a few survive to this day. Manuscript 632 was one of those that miraculously avoided being burned, and its preservation was guaranteed when it was purchased by a book collector named John Edward Gilmore in the 19 th century.

When Gilmore died in 1906, this rare item was acquired from his estate by the renowned pharmaceutical entrepreneur and collector of medical artifacts Sir Henry Wellcome, who added Manuscript 632 to his personal inventory.

Along with the remainder of Wellcome’s collection, the birthing girdle has been preserved to this day, and is currently on display at London’s Wellcome Collection library and museum.

Facing The Hazards Of Medieval Childbirth

The findings of this new Cambridge University study highlight the perils of childbirth in the medieval era.

“These results throw open the curtain onto a multisensory, vivid image of birthing,” said Kathryn Rudy, a University of St. Andrews historian. “They reveal the user’s hopes and fears—dread, really—about death in childbirth.”

Top image: Images of the MS. 632 birthing girdle. a) The dripping side-wound. b) The rubbed away green cross or crucifix. c) Tau cross with red heart and shield. Source: Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

By Nathan Falde