New Shocking Clues Into Human Origins From Qesem Cave

Just one week after it was announced that the inhabitants of the Qesem Cave, located 12 kilometers east of Tel Aviv in Israel, perhaps practiced swan shamanism as much as 420,000 years ago, comes evidence that these same individuals created the earliest known “canned food.” This took the form of purposely severed deer bones stored full of marrow, which would be specially stored to preserve their precious contents for an extended period of time.

The Qesem Cave in Israel. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The important study, published in the October 9 issue of Science Advances, was led by Dr. Ruth Blasco of TAU’s Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations and Centro Nacional de Investigación Sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH) and her TAU colleagues Prof. Ran Barkai and Prof. Avi Gopher.

Marrow Consumption

Ran Barkai, a spokesperson for the team, explains the findings: “Bone marrow constitutes a significant source of nutrition and as such was long featured in the prehistoric diet.”

“Until now, evidence has pointed to immediate consumption of marrow following the procurement and removal of soft tissues,” he adds. “In our paper, we present evidence of storage and delayed consumption of bone marrow at Qesem Cave.”

Experimental archaeological testing the longevity of marrow in deer leg bones. (Credit: Ruth Blasco).

His colleague, Dr. Blasco, takes up the story: “This is the earliest evidence of such behavior and offers insight into the socioeconomics of the humans who lived at Qesem. It also marks a threshold for new modes of Paleolithic human adaptation.”

“Prehistoric humans brought to the cave selected body parts of the hunted animal carcasses,” says Prof. Jordi Rosell of Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV) and Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social (IPHES), who with his colleagues conducted the experimental research on the longevity of severed deer metapodials. “The most common prey was fallow deer, and limbs and skulls were brought to the cave while the rest of the carcass was stripped of meat and fat at the hunting scene and left there. We found that the deer leg bones, specifically the metapodials, exhibited unique chopping marks on the shafts, which are not characteristic of the marks left from stripping fresh skin to fracture the bone and extract the marrow.”

Canned Food

It is believed that the deer metapodials would be kept at the cave protected by skins allowing the preservation of the marrow for consumption when required. In this way the bones were used as “cans” preserving the bone marrow for an extended period, after which the inhabitants would take off the dry skin, shatter the bone and eat the marrow. What this constitutes, therefore, is the earliest known evidence of food preservation and the delayed consumption of food.

As Ran Barkai points out:

“We show for the first time in our study that 420,000 to 200,000 years ago, prehistoric humans at Qesem Cave were sophisticated enough, intelligent enough and talented enough to know that it was possible to preserve particular bones of animals under specific conditions, and, when necessary, remove the skin, crack the bone and eat the bone marrow.”

- The Origin of ‘Us’: What We Know So Far About Where We Humans Come From

- The Stone Age: The First 99 Percent of Human History

- 11 Mysterious Human Species That Most People Don’t Know Existed

Innovative Behavior

This mind-blowing discovery joins other evidence of innovative behavior found in association with the inhabitants the Qesem Cave as early as 420,000 years ago. It includes the regular use of fire, cooking and roasting meat, specially-prepared sharp tools to cut meat, the recycling of materials, and what has been described as a “school of rock,” in the form of an on-site teacher-pupil relationship in stone tool manufacture.

This is in addition to the likelihood, already alluded to, that the Qesem individuals were involved in an early form of bird shamanism following the discovery of a 420,000-year old swan wing bone where the feathers had been purposely removed, an action suggesting that both the bird bone and the bird’s feathers were being used for shamanic practices with possible cosmological implications. If correct, then this constitutes the earliest manifestation of shamanism anywhere in the world.

Swan wing bone found in the Qesem Cave bearing evidence of modification. (Credit: Ruth Biasco)

Very clearly the Qesem individuals were not simply hunter-gatherers who lived from day to day, scavenging for food by whatever means possible. They created a sophisticated, organizing style of living that is unlikely to have existed in isolation.

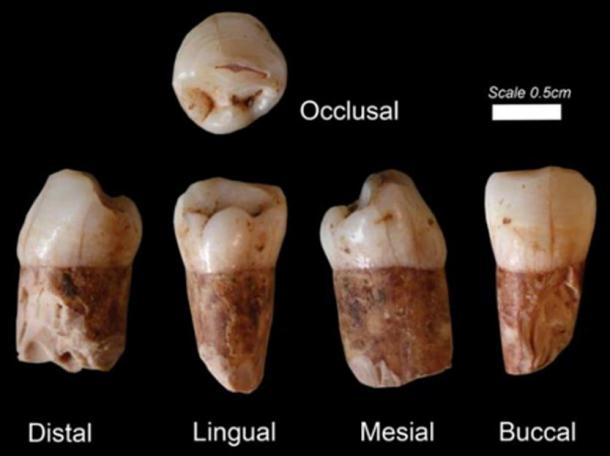

Adding further mystery to these discoveries is the fact that eight hominin teeth found in the cave and dating to at least 400,000 years ago closely resemble those of modern humans, while later examples found there bear characteristics closer to that of a Neanderthal-modern human admixture. This has suggested to some that modern humans ( Homo sapiens) originated not from Africa, where the oldest evidence of their existence comes from 300,000-year-old human fossils found at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco and 195,000 year old bone fragments found at Omo Kibish in Ethiopia, but in Israel.

400,000-year-old teeth from the Qesem Cave (Image: Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, Tel Aviv University CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Denisovan Link

So who were the advanced individuals who lived in the Qesem Cave as much as 420,000 years ago? Were they pre-dispersal modern humans ( Homo sapiens), that is human groups that having evolved in Africa moved into the Levant and were later either replaced by or absorbed into the Neanderthal populations of Southwest Asia? Or were they an early form of Denisovan, gradually moving through the Levant en route to the eastern part of the Eurasian continent, following their own split from Neanderthals around 380,000-470,000 years ago?

As one study from 2016 makes clear on the nature of the Qesem inhabitants:

“Their [the Qesem individuals’] origin is undetermined, but we cannot exclude that Denisovans, or their immediate precursors, inhabited the Levant [at this time, i.e. 400,000 years ago].”

In other words, they cannot discount the possibility that the Qesem individuals were linked in some manner to the Denisovans, who existed here prior to their own dispersal into the eastern half of the Eurasian continent.

Human lineage showing the possible origins of the Qesem individuals. (Author Provided)

So were the Qesem individuals pre-dispersal modern humans or early Denisovans on their way through Southwest Asia to places like the Denisova Cave in southern Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau in what is now northwest China, both having produced anatomical evidence of their presence as much as 100,000-160,000 years ago?

Just maybe the picture is even more complicated, with the Qesem individuals being hybrids composed of pre-dispersal modern humans and proto-Denisovans, a combination that perhaps gave them a unique mindset that enabled them to advance much quicker than their closest rivals elsewhere in the world.

Siberian Denisovans & Sunda Denisovans

Such a solution might explain why there are two distinct types of Denisovan. One branch existed in Siberia, the Tibetan Plateau, Mongolia, northern China and East Asia in general, and achieved a very high state of innovation including the invention of bones needles, musical instruments and a formative blade tool technology, before its disappearance around 45,000 years ago. These are known as the Siberian Denisovans. The other branch, called the Sunda Denisovans, possessed a more archaic genetic ancestry and would not appear not to have developed the same level of technological innovation as their northern rivals. For instance, they did not develop a blade tool technology of the type that was later adopted by the earliest modern humans to reach places like Siberia, Tibet and Mongolia. Instead they and their hybrid descendants would seem to have used a more basic flake tool technology of a type more common among the earliest modern human populations of Southeast Asia.

Thus it becomes possible that the Qesem individuals, as a fusion of pre-dispersal modern humans ( Homo sapiens) and proto Denisovans, were in fact the forerunners of the Siberian Denisovans, who as a hybrid population, after leaving the Levant, continued their journey eastward past the Caspian Sea into first North Asia and then finally East Asia. If correct, then a second strain of Denisovans, having departed Africa for the Saudi peninsular, most likely moved around the Persian Gulf into the Indian sub-continent before finally entering Mainland and then Island Southeast Asia, which at the time formed part of a much bigger landmass called Sundaland. Here they settled to become the Sunda Denisovans, some of their number possibly continuing the journey into the former continent of Sahul, modern-day Australia and Papua New Guinea. All of these territories have modern populations with anything up to 5-6 percent Denisovan DNA derived from Sunda Denisovan ancestry. Indeed, so high is its presence in places like Indonesia and the Philippines that in the opinion of some paleo-geneticists this would require the existence of a third type of Denisovan, an offshoot of the Sunda Denisovans, that might well have survived through till around 15,000 years ago, an exciting prospect indeed!

Swan Ancestry

If these ideas are correct, then they could explain why not only swan shamanism but also the concept of swan ancestry (tribes and clans claiming descent from a swan maiden, a genetrix in the form of a swan) developed among so many indigenous tribes and clans in former strongholds of Siberian Denisovans, most obviously Siberia, Mongolia, Tibet and North Asia as a whole. Very likely these ideas, which remain strong among certain communities even to this day, emerged among modern human communities during the Upper Paleolithic age circa 45,000-11,500 years ago, their claimed swan ancestry being a highly abstract memory of hybridization with Siberian Denisovans, who saw the swan as an important and very ancient symbol both of human origins and of human transformation into a preternatural bird of flight, in this instance a swan – beliefs and practices that almost certainly had their inception at places like the Qesem Cave in the Levant as much as 420,000 years ago.

The concept of swan ancestry, descent from a swan maiden genetrix, is common among Siberian, Mongolian and North Asian populations even today. Joseph Jacobs John Dickson Batten [Public domain]

All these ideas are at least possible, although much more information is required before they can be validated. What we can say for sure right now is that something very important was going on in the Qesem Cave some 420,000 years ago and how exactly this played out might well have huge implications for our understanding of the rise not only of anatomical modern humans, but also of other important hominin such as the Denisovans.

Top image: Possibilities for human origins are being explored with the finds at Qesem cave Israel. Source: ginettigino / Adobe Stock

Comments

Well, as most of us with an open mind do realize. Out of Africa is the African agenda. Western people and nations came from Mesopotamia. Asians, who knows?

Sir Clerke

Amazing to me that we can determine (or infer) so much knowledge about Denisovans based on such a small group of relicts and artifacts. Beginning with such a recent discovery, we now have possibly three different branches of that tree – add in the hybrids and Floriensis, and there are lots of different types of people out there somewhere in the maybe not so distant past.