Five Things We Learned About Our Human Origins in 2018

The question of what makes us human is one that is fascinating to most of us, and for many the answer lies in looking back to our roots as a species. 2018 was a fantastic year for learning new and exciting things about our origins, with ground-breaking discoveries and pioneering technology changing a number of perspectives and bringing new possibilities to light. From hybrid humans to signs of human behavior 300,000 years ago, these are some of the most significant stories from 2018.

Evidence of Modern Human Behavior in Ancient Africa

A number of finds at the Olorgesailie Basin in Kenya have proven that humans were exhibiting modern behavior as early as 300,000 years ago. Numerous obsidian artifacts were found at the site in 2018, providing strong evidence of trade networks, as obsidian is not native to Olorgesailie and must have been sourced from at least 55 miles (88.51 km) away.

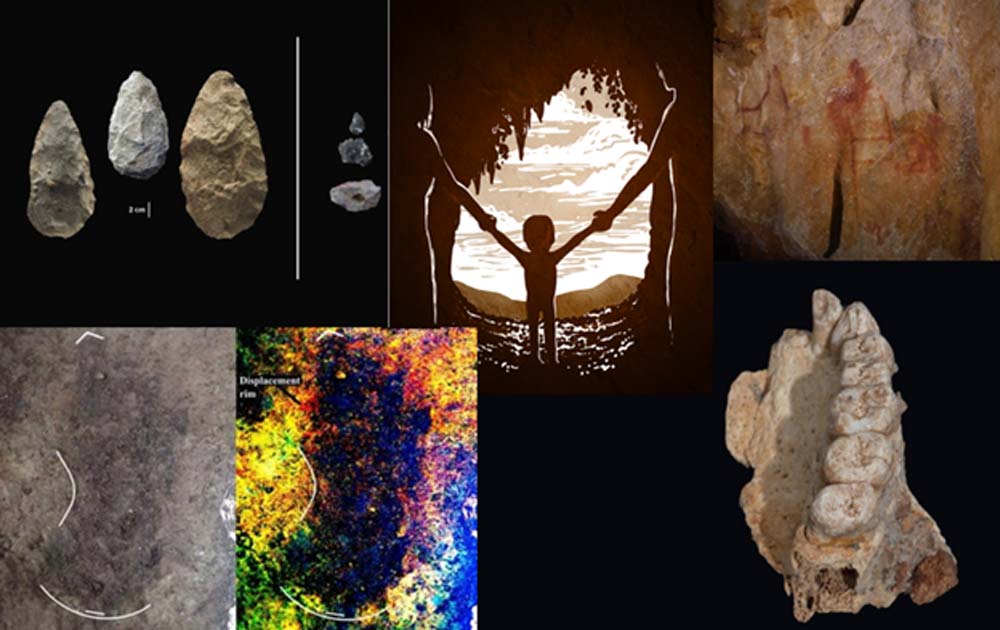

The first evidence of human life in the Olorgesailie Basin comes from about 1.2 million years ago. The sophisticated tools (right) were carefully crafted and more specialized than the large, all-purpose handaxes (left). (Human Origins Program, Smithsonian)

Along with the obsidian tools were finds of manganese dioxide and ochre, which showed signs they were processed to use their pigments.

- 13,000-Year-Old Footprints Found in British Columbia Are the Oldest in North America

- New Insights into Rapid Advance in Human Innovative Thinking

- Ancient Anomalous Human Skeletons: Humanity Could be Much Older Than We Think

This is particularly significant as it pushes the evidence of modern behavior in humans back tens of thousands of years before it was previously thought, aligning with the oldest known fossil remains of a modern human.

Neanderthals May Have Pioneered Cave Art

One traditional answer to the question ‘what makes us human?’ has been our ability to think symbolically and create art, but in 2018 scientists revealed the origins of some cave art in Spain was actually Neanderthal. The discovery adds more evidence to the theory that Neanderthals and modern humans were not as different to one another as previously assumed.

Panel 78 in La Pasiega. The scalariform (ladder shape) composed of red horizontal and vertical lines dates to older than 64,000 years and was made by Neanderthals. (C.D Standish, A.W.G. Pike and D.L. Hoffmann)

It was revealed that the art must have been created by Neanderthals after an international team of scientists dated the calcite (crystal) layer which had formed on top of the ancient artwork. As the calcite had formed over the art, the art must have been there beforehand and has to be older than it. Results revealed the artwork predated the arrival of modern humans in the region by a minimum of 20,000 years.

Humans Migrated ‘Out of Africa’ a Lot Earlier than Previously Thought

It is now known that modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago before migrating to other continents. In January 2018 a group of archaeologists from Tel Aviv University working at Mount Carmel, Israel discovered the upper jaw bone of a Homo sapiens in a layer of sediment with tools previously attributed to Neanderthals, pushing back the date for human migration out of Africa by about 40,000 years. This also confirms the theory that there was more than one expansion phase with different groups leaving Africa over a vast time period.

This is the left hemi-maxilla with teeth. (Rolf Quam)

The implications of this discovery are huge, as it suggests humans were behaviorally modern enough to communicate and organize migratory expeditions significantly earlier than was formerly assumed.

Oldest Modern Human Footprints in the Great White North

A group of modern humans left their mark on the Canadian island of Calvert, British Columbia approximately 13,000 years ago in the form of footprints. A team from the University of Victoria including representatives from the Heiltsuk and Wuikunuxv First Nations revealed the group of 29 footprints, which were made by at least three people, and are the oldest known footprints in North America. The footprints are a very rare find, as there are not many sites with footprints worldwide. One of the sets of prints was left by a child, and they seem to have been walking barefoot.

Photograph of track #17 beside digitally-enhanced image of same feature using the DStretch plugin for Image. (Duncan McLaren)

Despite Calvert being a tiny island today, the site may have been part of a route taken by humans when they migrated between Asia and the Americas during the late Pleistocene era.

First Confirmed Hominin Hybrid

The biggest archaeological discovery of 2018 probably came out of the already significant Denisova cave in Siberia. Ten years after the discovery of a new class of hominin ( Homo Denisova) at the site, a small fragment of bone has yielded stunning results after being positively identified as the direct offspring of a Neanderthal and a Denisovan. The female offspring, nicknamed ‘Denny’, had survived to approximately 13 years of age, meaning she was way beyond infancy and may have had children of her own.

Drawing of a Neandertal mother and a Denisovan father with their child, a girl, at Denisova Cave in Russia. (Petra Korlević)

The discovery was made by a team led by Viviane Slon and Svante Pääbo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. The team began by looking at Denny’s Mitochondrial DNA (passed to her by her mother) which showed it was Neanderthal in origin. However when they sequenced her nuclear genome and compared it to the genomes of Neanderthals and Denisovans from the cave, and a modern human with no Neanderthal ancestry, they found that about 40% of her DNA fragments were Denisovan in origin. As her Mitochondrial DNA was already confirmed to be Neanderthal, the conclusion was that Denny must have had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father, though Slon and Pääbo were careful not to use the word “hybrid” in their paper as debate about exact classification of our closest relatives is still ongoing.

- The Origin of ‘Us’: What We Know So Far About Where We Humans Come From

- Ancient Human Fossil Finger Discovery Points to Earlier Eurasian Migration

- Research Confirms that Neanderthal DNA Makes Up About 20% of the Modern Human Genome

There is certainly more to come on this in 2019 with the latest development already coming from an artificial intelligence genome study published in Nature Communications which has identified what looks like a Neanderthal-Denisovan hybrid species in the genome of Asian individuals.

It’s a good start to another year of getting closer to understanding the ancient origins of humankind.

Top Image: Key images from the top human origins stories of 2018: Sophisticated tools and large, all-purpose handaxes from the Olorgesailie Basin in Kenya. (Human Origins Program, Smithsonian) Drawing of a Neandertal mother and a Denisovan father with their child, a girl, at Denisova Cave in Russia. (Petra Korlević) Neanderthal cave art in La Pasiega, Spain (C.D Standish, A.W.G. Pike and D.L. Hoffmann) Photograph of a footprint beside digitally-enhanced image of the same feature. (Duncan McLaren) The left hemi-maxilla with teeth found at Mount Carmel. (Rolf Quam)

References

Buanes Duke, J-B. 2018. Astonishing Discoveries Shines new light on human evolution. https://www.uib.no/en/hf/116203/shines-new-light-human-evolution

Hershkovitz, I et al. 2018. The earliest modern humans outside Africa. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6374/456

Marris, E. 2018. Neanderthal artists made oldest-known cave paintings. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-02357-8

McLaren, D et al. 2018. Terminal Pleistocene epoch human footprints from the Pacific Coast of Canada. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0193522

Slon, V et al 2018. The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature (561) pp113