The Saga of Norna-Gest: Does Man Control His Destiny?

The tale of Norna-Gest goes down in literary record as a tale of destiny and a character’s attempt to fight it. Not one of the titular Icelandic sagas, Norna-Gest’s story was recorded around the year 1300 in Nornagests þáttr and in Flateyjarbók, the latter a compilation of episodes and poems. The myth touches on the fear of death, and one’s control over a perceived destiny.

Painting, The Norns, 1895. Public Domain

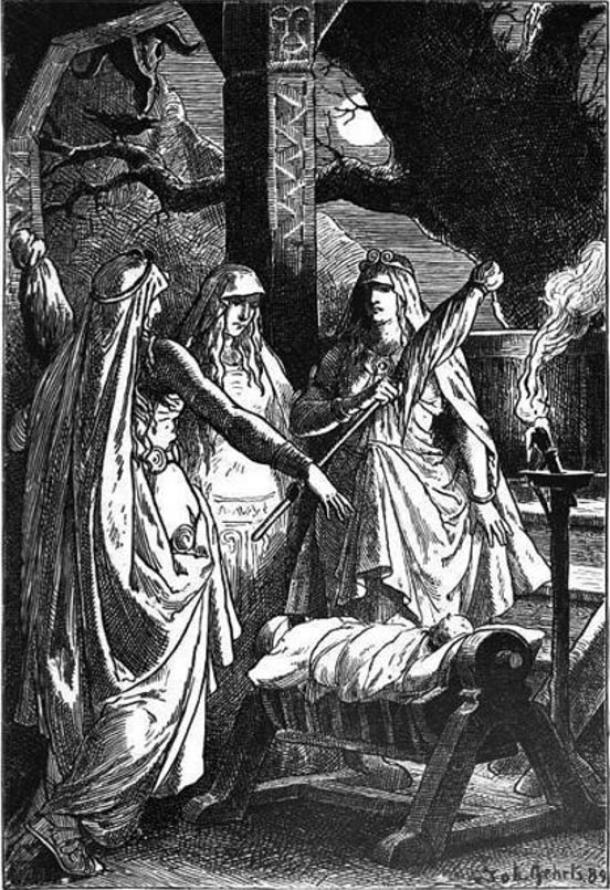

The legend is written that Norna-Gest, known most often as merely Gest in the translations of his saga, was born to Thord of Thinghusbit from Denmark. His tale took an immediate turn, however, because on the day of his birth, the Norns came to his cradle-side to bestow gifts upon him for unknown reasons.

Three women who controlled the destiny of men and gods alike, the first two Norns, Urðr and Verðandi, gave him kind, gentle gifts intended to provide him with a bright future. Contrarily, the third and youngest Norn called Skuld, dictated that Gest would die by the time the candle lit at his bedside went out. Immediately, Urðr extinguished the candle's flame and ordered Gest's mother to hide it and protect it to prevent her son from succumbing to Skuld's curse. Because of his mother’s constant protection, and her passing the task of guarding the candle onto him as he got older, Gest grew to live well into his three hundreds, a side effect of Skuld’s curse.

MORE

- The Haensa - Thorir Saga: A tale of law in Medieval Iceland

- The Tale of Thorstein Shiver: Hell Confirmed for Pagans during Iceland Saga Age

Illustration, the three Norns surround a child, deciding his fate. (1889) Public Domain

Gest's story was set in a time when Christianity began to permeate the northern countries, led by King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway. Interestingly, he found himself a guest of Tryggvason despite having only been baptized with the sign of the cross. The importance of Tryggvason's presence however, appeared to be a method by which Gest could recount the life he had led up to that moment.

When Tryggvason was presented with a ring that awed all of his men, Gest was the only one who stood out, not as amazed by it as Tryggvason’s other followers. Upon being questioned why he was so ambivalent about a gift to the king, Gest detailed his history, describing his centuries of adventures with some of Scandinavia's most favored characters.

He disclosed his time with Sigurd Fafnirsson, the great dragon-slayer who suffered because of the ring Andvaranaut forged by dwarves, and how he had fought at Sigurd's side. Sigurd, as it turned out, gave Gest part of a ring from his horse Grani’s chest harness, a far more valuable prize in Gest’s opinion than the ring which Tryggvason was given.

Gest continued to tell of his life, after providing evidence for his dislike for Tryggvason's ring. He explained that upon leaving when Sigurd died, Gest spent a period with the sons of Ragnar Lodbrok, the powerful Viking king of Denmark, as they were leaving for Rome.

The most surprising aspect of Gest’s story was that once he completed the lengthy description of his life over the previous three hundred years, he took out the candle that he had kept hidden for so long and lighted it, ending his life in that moment.

Though Gest's story is short, it has gained a lot of popularity as it is similar to another well-known tale: the Greek myth of Meleager.

Funerary relief entitled The Death of Meleager Roman 2nd century CE Marble. Mary Harrsch/Flickr

The myth of Meleager begins its relevancy with his birth. Like Gest, on the day he was born, the Fates—the Greek equivalent of the Norns—predicted that Meleager would die when a particular log was consumed by flames in the family hearth. At once, his mother Althaea took the log and sealed it away in a chest, never to be touched to prevent her son’s certain death. However, during the hunt for the Calydonian boar, Meleager aided a woman, Atlanta, in winning its hide as a prize. This angered his own brother. An argument between them came to a head when Meleager killed his brother, at which point Althaea then burned the log to avenge one son against the other.

The Three Fates of Greek mythology. Painting, 19 th century. Public Domain

As one can see, the similarities are high between the candle of Gest and the log of Meleager. Both had their demise prophesized by three sisters of fate, and both died at the mercy of the object keeping them alive.

One might also notice a small similarity to the European fairy tale Sleeping Beauty, however it is merely a surface comparison, as the pertinence only stems from the three gifts from three magical givers, one of whom used her final wish to undo another's spell. Even though in the fairy tale, there is a fourth witch who curses the child, the role of the third fairy is similar to that of Skuld in Gest's tale because her wish was meant to counteract only.

MORE

- The true meaning of Paganism

- 800-year-old body found in Norwegian well supports accuracy of Sverris Saga

The similar themes with Meleager’s tale, on the other hand, deal with the concept of death and a mother's fear for her son. It can be postulated that, not only did the Norns/Fates take the child's life out of his own hands, but the mother did as well, with Gest being given the better circumstance as the candle was always in his possession.

This theme of death and the fear both stories invoke is a powerful one, prevalent in ancient and medieval literature, as there has always been a concern for the next life and not living as one should before passing away.

In both Meleager's and Gest's stories, they are given those chances before dying; Meleager’s acts instigating his death while Gest lived until he decided he had seen and done enough.

Featured image: Detail, Illustration from the title page of a manuscript of the Prose Edda, showing Odin, Heimdallr, Sleipnir and other figures from Norse mythology. 18 th century. Public Domain

Bibliography

Anderson, George K., trans. The Saga of the Völsungs: Together with Excerpts from the “Nornageststháttr” and Three Chapters from the “Prose Edda” (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1982, 171-191.)

Hamilton, Edith. Mythology (Warner Books: New York, 1969.)

Hollander, Lee. "Notes on the NORNAGESTS ÞÁTTR" Publications of the Society for the Advancement of Scandinavian Study, 3.2, July 1916, pp. 105-111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40914976

McDonald, Sheryl. “Pagan Past and Christian Future in: Norna-Gest þáttr and Bárðar saga Snæfellsáss.” Presentation, University of Leeds, 2009. https://www.academia.edu/1186234/Pagan_Past_and_Christian_Future_in_Norna-Gests_%C3%BE%C3%A1ttr_and_B%C3%A1r%C3%B0ar_saga_Sn%C3%A6fells%C3%A1ss

Munch, Peter Andreas. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes, trans. Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt (New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1926.) http://files.meetup.com/262110/munch-pdf.pdf

Price, Neil. The Viking World (Routledge: London, 2008.)

Sanmark, Alexandra. Power and conversion: a comparative study of Christianization in Scandinavia; Uppsala (Department of Archaeology and Ancient History: Uppsala University, 2002.)

By Ryan Stone