The Runamo Runes: The Mysterious Runic Inscription that Never Was!

Before the invention of paper, humanity often inscribed words, symbols, and images onto the living stone of the surrounding landscape. These images, often commemorating significant cultural events or telling ancient stories, are studied by modern scholars to piece together narratives of various ancient cultures. As is the case with all scholarship, however, there are those who get carried away in the moment and allow flights of fancy to dictate their studies. The ‘Runamo Runes’, carved into the Runamo Rock in Sweden, are an example of such a mistake.

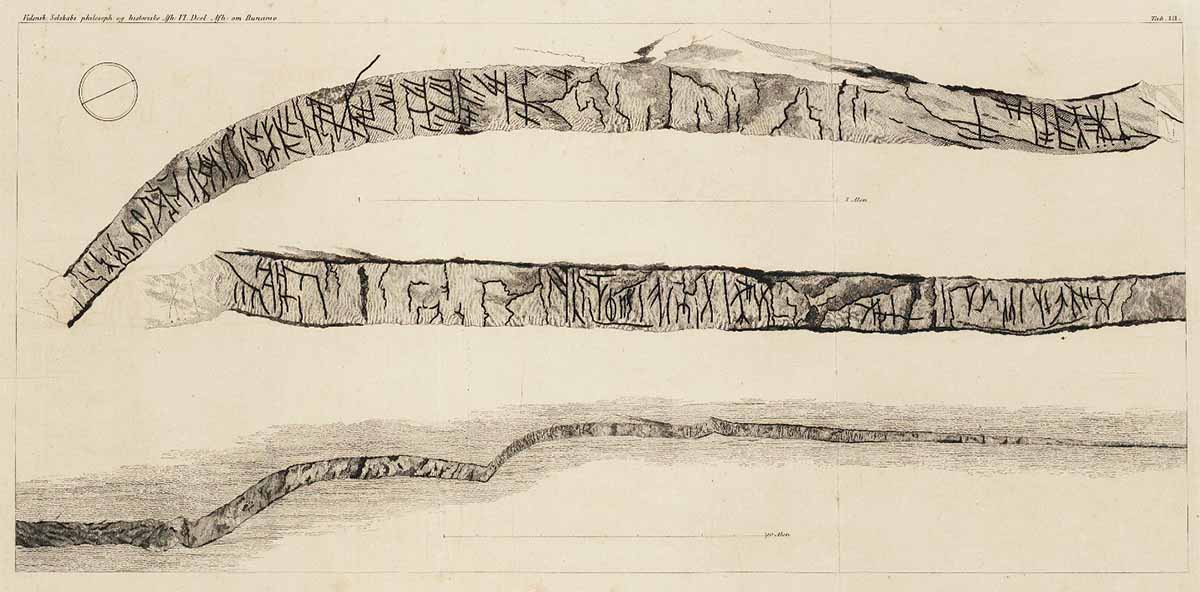

An illustration of the ‘Runamo Runes’ inscription by Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae. (Public Domain)

The Foundations of an Enduring Myth

Saxo Grammaticus is regarded as one of the earliest historians of Denmark. A 12th-13th century scholar, Grammaticus was the first to note the supposed runes inscribed on a cliff face in Blekinge in the south of Sweden in his book, the Gesta Danorum. Initially, he described the runes as illegible and stated that men sent by King Valdemar to inspect the site could not make out any words. Later, however, he attributed the carving of the runes to King Harald Hildetand of Denmark, also known as Harald Wartooth. His father, Hrœrekr Ringslinger, according to history and legend, had waged a successful war to unite Sweden and Denmark. According to Grammaticus, the inscription was a memorial to the great deeds of Hildetand’s father.

- Saxo Grammaticus: Warrior Historian of the Danes and a Medieval Influencer

- Fakes and Controversy on the River Clyde: The Case of Dumbuck Crannog

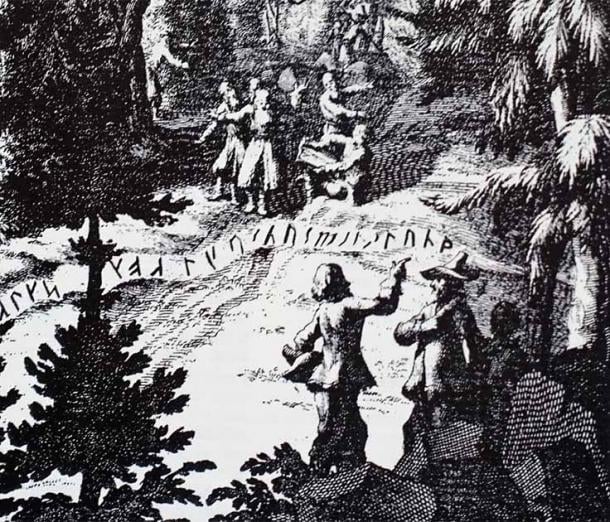

Archaeologists really wanted to believe that the ‘Runamo Runes’ were inscribed by King Harald Wartooth – so much so that they bent evidence to their opinions (Public Domain)

There is, however, no explanation in the Danorum as to what changed Grammaticus’ opinion, leading many modern scholars to question the validity of his conclusion regarding the meaning of the runes. If the runologists could not make out any discernible words or phrases, how did Grammaticus come to his ultimate conclusion?

A surviving fragment of the Gesta Danorum in Saxo’s own handwriting (Public Domain)

The Rising Debate Surrounding the Runamo Runes

The Runamo Runes faded from academic imagination for nearly five centuries after Grammaticus published his book. Then, in the 17th century, a Danish antiquarian by the name of Ole Worm sent his assistant to Blekinge to examine the rock. Jonas Skonvig reported to Worm that the runes were largely illegible, but he believed he could make out a single word: Lund, which translates to grove. Worm published these ‘findings’ alongside a series of illustrations.

Later expeditions throughout the 18th century found no more than Skonvig had, yet the growing myth was evident in the illustrations coming out of those academic journeys. The word “lund” appeared unquestioningly in every report and image, as each became more fanciful and romanticized. Concurrently, other scholars like Nils Reinhold Brocman began seriously debating whether the marks meant anything. In his book, Ingvar Saga, Brocman questioned Grammaticus’ contradictory conclusions, and also wrote to a friend asserting that he’d been to the Runamo Rock and found nothing but naturally occurring cracks in the stone.

- Runes of Power and Destruction: Reading the Cursed Runestones of Sweden

- Pseudo-History or Famed Fiction? Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia

1712 engraving of the expedition for the so-called Runamo Runes (Public Domain)

A Meaning Revealed…and Rejected

It was not until the 19th century that the full meaning of the runes was supposedly revealed. In 1833, the Danish Academy of Sciences sent a commission to investigate the Runamo Runes, composed of antiquarian philologist Finnur Magnussun, historian Christian Molbech, and geologist Johan Georg Forchhammer. Forchhammer was tasked with examining the markings and highlighting those he believed to be man-made, all without Magnusson’s involvement to ensure there would be no tainting of the ostensibly scientific process. After this was finished, the highlighted runes were transferred to copper plates and given to Magnusson, who took them home for analysis.

Illustration of the official Danish ‘Runamo Runes’ expedition in 1833, by C.F. Christensen. (Public Domain)

After much fruitless investigation, Magnusson could not decipher any meaning. Suddenly, he decided to read the inscriptions in a different order, from right to left, according to conventions from ancient Icelandic texts, despite this being a rare occurrence. In doing so, he believed the meaning was revealed! Magnusson published his translation of the runes, stating that they spelled out an ancient ode to King Hildetand (Hildekind) and the Battle of Bravalla.

Magnusson’s assertions, however, were roundly rejected by natural scientists and antiquarians. Jacob Berzelius, Sven Nilsson, and Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae were quick to study the runes and Magnusson’s reports in depth and refuted them through geological investigation, including the use of plaster to make casts of the cracks. The debate stirred up surrounding the runes was intense, with a large number of published books and letters emerging throughout the scholarly community on both sides. Ultimately, it was concluded that the runes were nothing more than natural cracks in the stone, formed by ancient volcanic activity.

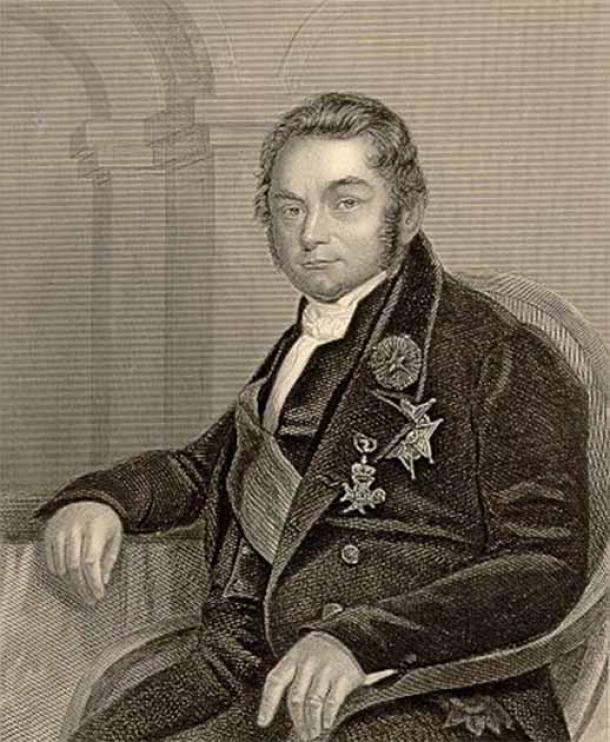

Swedish chemist Jöns Jakob Berzelius was among those who said that the so-called Runamo Runes were only natural cracks in the rock from volcanic activity. 1875 engraving. (Public Domain)

The Aftermath of the ‘Runamo Runes’

Magnusson and Forchhammer were both respected academics and remained so after the debate. They were criticized for giving in to imagination and a desperate desire for sweeping discovery, but they continued to be mostly well regarded in the scholarly community. In 1878, Chas Rau published an article in The American Antiquarian regarding another stone inscribed with supposedly Nordic runes, the Dighton Rock. Magnusson was once again tapped to examine the markings, and once again interpreted their meaning, this time stating that the runes were a statement by 151 “Northmen” who had arrived at that location centuries earlier. Rau questioned the translation and Magnusson’s reliability, citing his work with the Runamo Runes. However, perhaps unknowingly, Rau also alluded to a deeper truth.

Icelandic scholar Finnur Magnusson believed the Runamo Runes were ancient inscriptions, later determined to be natural formations (Public Domain)

Rau stated of the Americans’ excitement that “it is not surprising that a people to whom, owing to the short duration of its existence, the romantic element of an ancient history is denied” should be susceptible to such a sketchy story. We all want to understand our roots and where our respective cultures came from, and everyone at one point or another has sought to glorify their past in some way. It is an easy trap to fall into, especially when globally surrounded by ancient markings and pictographs, to see meaning in every scratch upon the stone. However, sometimes a rock is just a rock; often, any meaning deeper than that may well be assigned by a deeper, intangible desire to understand our own history.

Top image: The ‘Runamo Runes’ inscription, according to Finnur Magnusson in 1841 (Public Domain)

By Mark Johnston

References

Rau, C. April 1878. Observations on the Dighton Rock Inscription. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/89622453?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true.

Rix, R. 2005. “Letters in a Strange Character”: Runes, Rocks, and Romanticism. European Romantic Review, vol. 16, no. 5.

Odelberg, W. 1995. Jacob Berzelius and Antiquarian Research. Laborativ Arkeologi. Available at: https://www.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.401108.1536843253!/menu/standard/file/LA8.Odelberg.pdf.

Comments

Meh on the scratchings, ...unless they can tell us something interesting like how the fair-haired wound up way up there coming OUT of the Ice Age?

Nobody gets paid to tell the truth.