Coatlicue: Fearsome Fertility Goddess of the Aztecs

Coatlicue was one of the most important gods in the Aztec pantheon. Not only was she the goddess of fertility, but she also gave birth to Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war and the sun. Her high ranking in the pantheon doesn’t mean she received the respect she deserved, however. Many Aztec gods came to violent ends, and Coatlicue was no different, slaughtered by her own children.

Coatlicue and the Bloody Birth of Huitzilopochtli

The primary myth that Coatlicue appeared in was the birth of her son, Huitzilopochtli. At the beginning of the story, Coatlicue is a humble priestess (or earth goddess, depending on the version) who had been tasked with maintaining the shrine atop the legendary mountain Coatepec, also known as Snake Mountain.

One day, as she was doing her daily chore of sweeping the floor, a ball of feathers fell from the heavens and landed in front of her. Thinking little of it, she picked the ball up and placed it in her apron pocket. For reasons lost to time, placing the ball in her apron magically impregnated her. Being a magical birth, she soon started to show. The problem was Coatlicue’s other children were not exactly enamored with the idea of having another sibling.

Coatlicue already had a daughter, Coyolxauhqui, as well as four hundred sons, the Centzonhuitznahua. Coyolxauhqui was a powerful goddess in her own right, as she represented the moon, and her brothers represented the myriad stars in the sky.

- Huitzilopochtli: The Hummingbird War God at the Forefront of the Aztec Pantheon

- Religion of the Aztecs: Keeping the Balance in an Unpredictable and Terrifying World

A colorized version of a massive monolith of Coyolxauhqui, daughter and murderer of goddess Coatlicue. (Gwendal Uguen / CC BY NC SA 2.0)

For some reason, Coyolxauhqui felt that her mother had somehow dishonored herself. Why, we do not know. Perhaps she did not believe it was an immaculate conception. Part of Aztec belief was that dead warriors were reincarnated as hummingbirds. In some forms of the myth, the ball of feathers is referred to as a ball of hummingbird feathers. This suggests that some random deceased soldier had impregnated Coatlicue.

If this is accurate, then it could explain Coyolxauhqui’s rage. How could her mother, a goddess, allow herself to be impregnated by some random dead soldier? It would also explain why Huitzilopochtli was the Aztec god of war; he was the son of a soldier.

- Xochiquetzal: Aztec Goddess of Beauty, Pleasure and Love… But Don’t Mess With Her!

- Art of an Empire: The Imagination, Creativity and Craftsmanship of the Aztecs

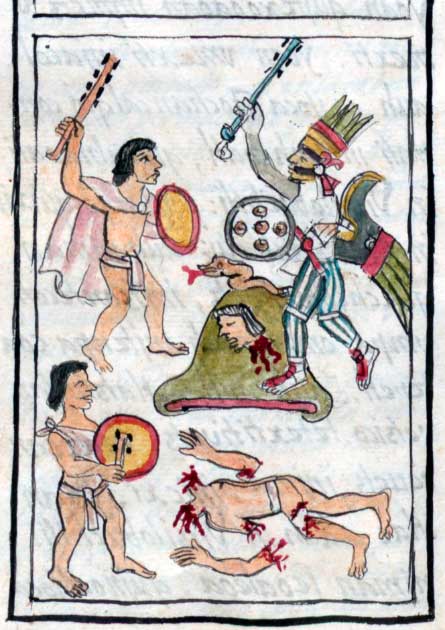

Illustration of Huitzilopochtli, from the Codex Telleriano-Remensis (Public Domain)

For whatever reason, upon hearing of the pregnancy, Coyolxauhqui flew into a rage and convinced her brothers to join her in storming Snake Mountain and attacking their mother. Luckily for Coatlicue, one of her children was still loyal. One of the Centzonhuitznahua reached out and warned Coatlicue and her unborn son of the attack.

From this point onwards, there are two existing versions of the myth. In one, Coyolxauhqui and her brothers’ attack was successful at first. They stormed the mountain, attacked their mother, and finished her off by decapitating her. This backfired, however, when Huitzilopochtli sprang from his dead mother's neck, in full war regalia. He massacred the majority of his brothers and beheaded his sister, doing so with such force that her head flew into the sky, becoming the moon.

The second version of the story has a happier, albeit equally bloody ending. This time as Coyolxauhqui approached her mother, ready to attack, Huitzilopochtli pounced from the womb first. Armed with his signature weapon, xiuhcoatl (fire serpent), he butchered his sister and brothers. He chopped his sister into many pieces and rolled them down the mountainside.

Illustration of the Battle of Coatepec from Bernardino de Sahagún, General History of the Things of New Spain, also known as the Florentine Codex, circa 1577 (Public Domain)

As Huitzilopochtli was the god of not just war but the sun, and Coyolxauhqui was the moon goddess it has been suggested that the myth symbolizes the daily victory of the sun over the moon and stars.

Coatlicue’s Monstrous Appearance

Before anyone starts to feel too sorry for Coatlicue, it must be stated that Coatlicue was often depicted as a monster who had a penchant for devouring humans. She’s most commonly portrayed as wearing a skirt of writhing snakes and a necklace adorned with alternating severed hands and human hearts.

Statue of Coatlicue from Cozcatlán, Puebla, Mexico, wearing typical snake skirt. Displayed in the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City (Anagoria / CC BY 3.0)

She is also often shown as having a face and arms made up of snakes. Her hands and feet have large claws, which she used to rip up her victims' bodies before she feasted on them. Coatlicue was closely connected in Aztec myth to the demon race known as the tzitzimime. The Aztecs believed that Coatlicue and these demons would ravage mankind if the sun ever failed to rise.

Depiction of a Tzitzimitl from the 16th century Codex Magliabechiano. (Public Domain)

Coatlicue Predicts the Fall of the Aztec Empire

Unlike many religions, the Aztec belief system was dynamic. This means that the Aztecs believed their gods were still hard at work, rather than believing all their myths were ancient tales of bygone eras. As such, new myths kept emerging, right up until the Spanish arrived and put an end to the Aztecs and their myths.

During Moctezuma’s reign (1440-1469 AD), sixty magicians were sent to visit Coatlicue at her home in Aztlan. They had been sent to deliver gifts in the hope of receiving divine knowledge as a reward. These magicians claimed that upon their arrival, they were met by Coatlicue’s tutor, who agreed to let them see the goddess. To reach her they had to climb a steep, sandy hill. The magicians soon began to struggle; they were overburdened by the gifts they had brought and became bogged down in the sand. In the end, they had to ask the tutor to take the gifts to Coatlicue for them.

The coronation of Moctezuma, from the Tovar Codex, circa 1585 (Public Domain)

The tutor once again agreed and, taking the gifts, ran up the hill as if the burden was nothing. When they eventually reached the top of the mountain, the magicians found Coatlicue sitting on the summit, weeping for her lost son, Huitzilopochtli. Upon seeing the magicians she admonished them for their weakness, telling them they had become spoiled and fat on too much luxury. In short, she told them they had gone soft.

She said the result of this was that, one by one, all the cities Huitzilopochtli had conquered for the Aztecs would fall. Eventually, the Aztec empire would lay in ruin. Then she would rejoice, for her favored son would finally return to her side.

A mural of Coatlicue in San Diego, California USA (Nathan Gibbs / CC BY NC SA 2.0)

Conclusion

While the Greek, Roman, and Norse gods could be scary if you got on their bad side, the Aztec pantheon makes them look like puppy dogs. The Aztec gods were largely a race of terrifying monsters who loved nothing more than eating their worshippers.

Even their goddess of fertility, Coatlicue, is terrifying. The monstrous nature of the Aztec gods just makes their mythology more fascinating. Tragically, when it comes to the Aztecs we still have lots of gaps in our understanding; much of their history was lost following the Spanish conquest of 1521.

Hopefully, one day these gaps will be filled, so that the Aztec gods can become as famous as their Greek, Roman, and Norse counterparts. Often overlooked, Aztec mythology deserves its time in the spotlight.

Top image: Left: Standing nearly 9 feet tall, this Coatlicue statue is one of the Aztec Empire's largest surviving sculptures. As was typical of Aztec sculptures, all sides of the statue were decorated. Right: A modern reimagining of Coatlicue. Source: Left: Luidger / CC BY SA 3.0; Center: Public Domain), Right: Public Domain

By Robbie Mitchell

References

Cartwright, M. November 28, 2013. Coatlicue. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Coatlicue/

Kilroy-Ewbank. L. August 9, 2015. Coatlicue. Smarthistory.com. Available at: https://smarthistory.org/coatlicue/

Miller, M.E & Taube K. 2013. An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. Thames & Hudson

Meehan, E. November 7, 2022. Coatlicue. Mythopedia.com. Available at: https://mythopedia.com/topics/coatlicue

Read, K. 2002. Mesoamerican Mythology. Oxford University Press.