Bestiary, The Book of Beasts: Compendiums of Medieval Monsters and Moral Lessons

During the Middle Ages the phoenix rose from its ashes to be reborn, dangerous dragons battled elephants to the death, and the pelican tore out its own breast to feed its young with its life’s blood—at least, these were the vividly illustrated lessons found in ancient bestiaries.

A bestiary, or Bestarium vocabulum is a book of beasts. Rich, decorative images illuminated in gold and silver showcased a compendium of living animals and birds, rare and common, and mythological creatures, benign and dangerous. These illustrated volumes, popular throughout North Africa, the Middle East and especially Europe during the 12 th century, not only contained observations on the natural world, but also imparted a moral lesson to medieval readers.

The Leopard, from the 13th-century bestiary known as the "Rochester Bestiary. (Public Domain)

According to David Badke’s The Medieval Bestiary, the Middle Ages was an intensely religious time, and it was believed in the Christian west that the animal kingdom and the natural world had been set down by god to provide instruction to humanity. In this view, humans were felt to be within nature, but apart from it. “Animals were said to have the characteristics they do not merely by accident; God created them with those characteristics to serve as examples for proper conduct and to reinforce the teachings of the Bible.”

Goats, cats, rabbits, cows: animals beautifully depicted in the 12 th century Aberdeen Bestiary. (Public Domain)

Thus, certain creatures represented certain ideals: the king of beasts, the lion, represented Jesus and his lordly position. The elephant was a model for human moral behavior and chastity, as it was believed to mate only once—not for pleasure, but only in order to bear young.

The Physiologus, Animals Ordered by Wild Traits

These compendiums were influenced by the original manuscript dated to between the second and fourth centuries AD. The Physiologus text (meaning "The Natural Historian" or "Naturalist"), written by an unknown author in the original Greek was translated into Latin around 700 AD, and then into many different languages across Europe and the Middle East. This opened up these regions to strange and surprising European beasts and legendary creatures, as well as the moral lessons and meaning of the animals within.

A panther, from the Bern Physiologus, circa ninth century. (Public Domain)

The ancient text, believed to have been written in Alexandria, contained approximately forty animals native to northern Africa, as well as their imagined traits and habits. Each animal was associated with a symbolic and moralizing interpretation.

The Physiologus is said to be one of the most widely distributed and copied book of the time after the Christian Bible. Indeed, medieval ecclesiastical art and literature was heavily shaped by the symbolism of the animals, and these interpretations survived in Europe for over a thousand years.

- Ancient Symbolism of the Magical Phoenix

- Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana: A Treasure Trove of Ancient Manuscripts

- Ten incredible texts from our ancient past

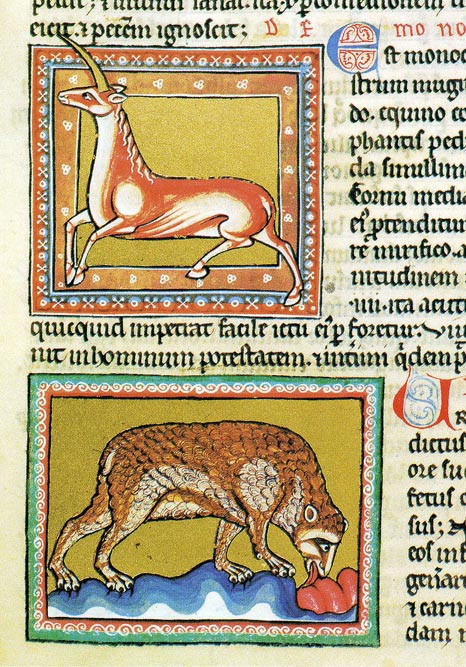

A monoceros (unicorn) above and bear below. The bear was said to give birth to formless, fleshy young, which it would then shape into small bears with the licking of its tongue. Ashmole Bestiary, c. early 13 th century. (Public Domain)

A Copy of a Reproduction of a Translation

Many bestiaries were made based on the translated information found in the Physiologus, but additional interpretations were added, and these later manuscripts were not exclusively religious, but a description of the world as it was known at the time.

Thus, an Icelandic bestiary included local fauna—fewer elephants and more birds and seals—so as to impart a more relevant message and important moralization to people of the area. In particular, the notable inclusions of the whale and the mythical Siren represented the northern tundra environment. It is believed translators writing far-flung bestiaries excluded certain animals because they’d never seen or heard of the strange foreign beasts, and were confused about the source entries. (However, these were uncomfortable edits to make, as it was seen as challenging or disbelieving the word of the church, and god).

The Fantastic Beasts, Symbols of Good and Evil

Each animal, real or imagined, imparted a lesson through the language of symbolism. While painted as dangerous, most of the animals represented both good and evil, and were possessed of both traits.

In bestiaries it was written:

The lion was king of the beasts (and directly connected to Jesus in an allegory that is repeated to this day). Lions were said to sweep away its tracks with its tufted tail, to sleep with its eyes open, and to be afraid of white cockerels.

The elephant, the most popular in bestiaries, was believed a chaste creature, only mating once. It copulated modestly, back-to-back, satisfying the medieval ideal that sex in marriage was for reproduction – not pleasure. The elephant was said to have no joints in its knees, and was usually depicted with a howdah or tower on its back.

The stoic elephant, war tower on its back, pursues a green, winged dragon. Circa 13 th century. (Public Domain)

The mythical griffin had the wings and head of an eagle, the body of a lion, and was said to violently attack and kill horses.

Antelopes, or Antalops, had long horns which they used to cut down trees. If they became tangled in branches, it would scream and bellow to be set free, and would become easy prey for hunters who were alerted by the noise.

The whale- or turtle-like aspidochelone was a huge sea monster. Because its back was huge and craggy, and covered with greenery, it was often mistaken for an island in the sea. It was believed to lure sailors to land on its back, and then would purposefully pull them under the water to their deaths. According to bestiaries, aspidochelone represented Satan, who “who deceives those whom he seeks to devour.”

The Aspidochelone lures hapless mariners to land on its back. Danish Bestiary, c. 1633 (Public Domain)

The boar was considered the most savage of all animals (and that’s something, as the dragon was seen as a dangerous, deadly foe). It was associated with the Antichrist, and was “capable of killing hunters with its formidable tusks; furthermore it personified the cardinal sin of Lust, in polar opposition to the virtue of Chastity. In this symbolism, the boar was lecherous and gluttonous beyond measure, capable of feeding on its own young, human corpses and small children.” For all of that, the boar was believed to personify strength and bravery, as it was both powerful and fearless.

- Beast Created to Protect the Jews

- Ten Mythological Creatures in Ancient Folklore

- Hereford Mappa Mundi: Legendary Cities, Monstrous Races, and Curious Beasts in a Single World Map

Dragons were believed to be the natural enemy of the elephant, and would dispatch them without compunction. The dangerous serpents had their power in their lashing tails, and not so much its teeth or breath. It would coil around prey and suffocate them. Said to originate in India and Ethiopia, it was believed they feared the Peridexion tree, which would harm them with its shadow. As well, dragons could not tolerate the roar of a panther, and would run and hide at the sound.

Doves hide in the Peridexion tree to avoid dangerous dragons. Oxford Bestiary, c.1220. (Public Domain)

Bestiaries remain beautiful, ancient works of art and literature showcasing the beliefs and fears of medieval people and their view of the natural world. They also convey the richness and importance of cultural myths, as the wild animals and strange, imaginary beasts found in the aged pages are still widely known and referenced today in popular culture.

Featured image: Strange beasts, mythological and real, graced the pages of ancient bestiaries. (Public Domain)

By: Liz Leafloor

References

Badke, David. “The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages.” 2010. Bestiary.ca [Online] Available here.

Grout, James. “The Medieval Bestiary”. 2015. Encyclopædia Romana. Uchicago.edu [Online] Available here.

Classen, Albrecht (Ed.). “ Handbook of Medieval Culture. Volume 1” . Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015. [Online]. Retrieved 18 Nov. 2015, from http://www.degruyter.com/view/product/179332

Rose, Carol. “ Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth”. 2001. Published by WW Norton

Comments

Fascinating – thank you! Provides a glimpse into the very different world view of our medieval ancestors. Beautiful artworks too.

Reminds me of the medieval wall paintings that used to adorn parish churches in the uk, with their symbolic moral messages. Very few examples of these left.

Thank you for the article!

Sculptures, carvings & artwork inspired by a love of history & nature: www.justbod.co.uk