The Rage of Horemheb: Hurried End of Akhenaten, Aye and Atenism – Part I

Barely four years after the death of Nebkheperure Tutankhamun in 1323 BC, the powerful ruling family was overthrown by Horemheb, a general and one-time non-royal crown prince; ending the Thutmosid line - and later, the Eighteenth Dynasty itself - that had lorded over Egypt and taken her to heady heights over a span of 250 years. Religious upheaval, glaring nepotism and corruption among the ruling elite had very nearly destroyed the glory of the empire. But, Horemheb would soon learn that the path to become pharaoh was fraught with great peril and challenges, in the form of political machinations by a powerful contender, Aye, and much drama at the royal court.

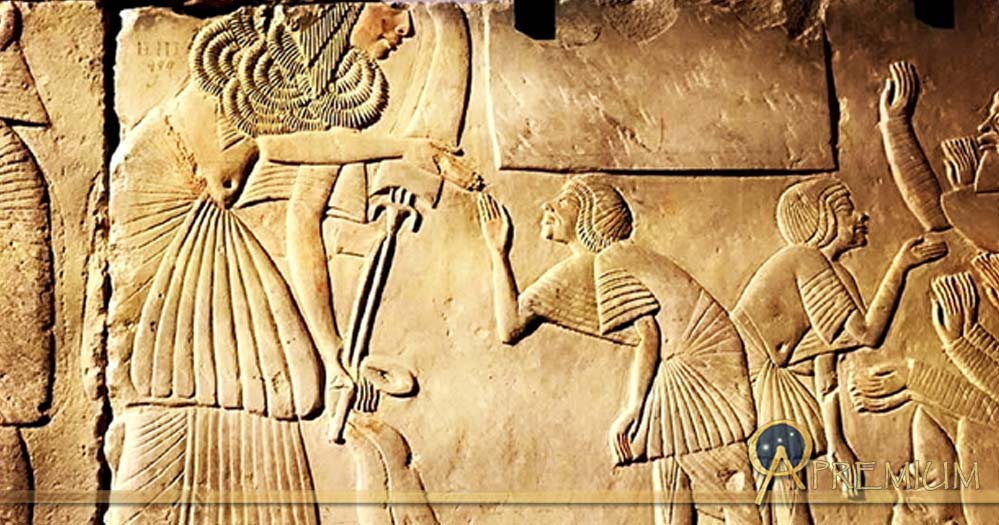

A painted limestone relief from the Memphite tomb of Horemheb shows him seated before an offering table. This elaborate sepulcher was built when he was a Generalissimo; the uraeus on his brow was added after he became pharaoh.

Horemheb Ascends to Greatness

Following the sudden demise of the boy-king Tutankhamun, two individuals who had played pivotal roles in the aftermath of the Amarna interlude rose to become pharaohs in quick succession—Kheperkheperure Aye and Djeserkheperure Setepenre Horemheb. Several Egyptologists opine that a power struggle arose between the two formidable friends-turned-foes, after Neferkheperure-waenre Akhenaten’s stab at monotheism failed. Horemheb, the last king of the Eighteenth Dynasty who saved the empire from the brink, came to the throne around 17 years after the Heretic’s death: Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten Smenkhkare-Djeser-Kheperu or better known as Akhenaten (three years), Tutankhamun (10 years) and Aye (four years). The Amarna fiasco was still fresh in the minds of the populace.

Thousands of Talatat lie in the precincts of Karnak Temple today. It will take a Herculean effort to piece together this massive Amarna-era jigsaw puzzle. However, we have learned much from many assembled blocks. (Right) The Ninth Pylon built by King Horemheb using Talatat blocks from Akhenaten’s structures as fill. (Photo: Francesco Gasparetti)

The erstwhile Generalissimo, Horemheb, was largely successful in expunging the names of Amarna kings from the records. He did so with an undeniable vengeance and in haste. And in doing so, he sent a clear message that the crown would not tolerate an affront to Ma’at. Two decades after Akhenaten’s death, all vestiges of his era were obliterated. The unforgiving desert sands did the rest, and soon swallowed the last traces of Akhetaten, his palace.

Like this Preview and want to read on? You can! JOIN US THERE ( with easy, instant access ) and see what you’re missing!! All Premium articles are available in full, with immediate access.

For the price of a cup of coffee, you get this and all the other great benefits at Ancient Origins Premium. And - each time you support AO Premium, you support independent thought and writing.

More upcoming in Part II, an Ancient Origins Premium series by independent researcher and playwright Anand Balaji, author of Sands of Amarna: End of Akhenaten

Special thanks to Dr Aidan Dodson for granting permission to use exclusive photographs.

[The author thanks Merja Attia, Heidi Kontkanen, Dave Rudin, Anneke Bart and Hussein Badawy for permission to use their photographs.]

Top Image: Fragmentary scene, originally from the second courtyard of his Saqqaran tomb, shows Horemheb wearing the Gold of Honor given by Tutankhamun; design by Anand Balaji (Photo credit: Anneke Bart)

By Anand Balaji

Comments

Interesting fresco. The chair has similar feet as the Thera tripod chair, https://media-cdn.tripadvisor.com/media/photo-s/0e/49/91/fa/an-ancient-t... The Egyptians seem to like the idea of sitting on an animal, as in the master/mistress of animals. All the rulers around this region and period seem to want to convey their mastery of domesticated and wild animals. The quality of the furniture is amazing, it's as fine as Chippendale. Amazing.