Cataphracts: Armored Warriors and their Horses of War

By the 7 th and 8 th centuries B.C., the role of the chariot in battle was gradually being replaced by cavalry units in the Near East. Some were armed lightly and were used to harass the enemy from afar with missiles or to pursue routing troops. Other types of cavalry units were heavily armed, and were used as shock troops to break enemy formations. The most heavily armed cavalry unit in the ancient world was the greatly feared cataphract.

Origins of the cataphract

The word ‘cataphract’ has its origins in the Greek language, and is said to mean ‘fully armored’ or ‘closed from all sides’. The cataphract, however, was not a Greek ‘product’, and was only adopted by the armies of the Seleucid Empire sometime during the 4th century B.C., after they went on military campaigns against their eastern neighbours. It has been pointed out that one of the earliest known depictions of the cataphract can be found in Khwarezm, a region in Central Asia near the Aral Sea. This image portrays a warrior clad in armor, armed with a lance and bow, and mounted on an armored horse. It has been estimated that these cavalrymen were used in the region as early as the 6 th century B.C. Apart from the Seleucids, various other Central Asian nations also had cataphracts in their armies.

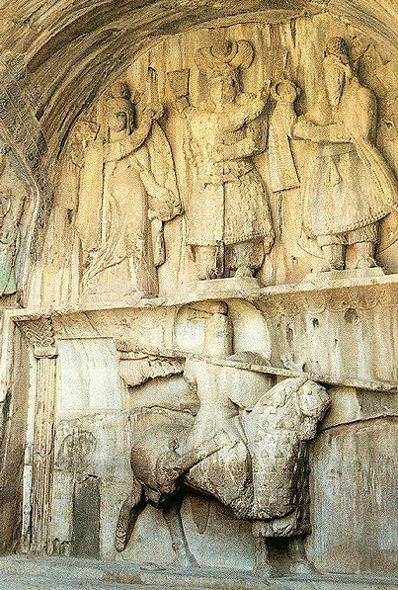

Relief Taq-e Bostan (Kermanshah Province in Iran) from the era of Sassanid Empire: One of the oldest depictions of a cataphract. The figure on top in the middle is believed to be Khosrau II. The figure to the right is Ahura Mazda, and to the left is the Persian Goddess Anahita. The cataphract is not known, although various theories exist on his identity, but he is certainly of royal nobility. (Wikimedia Commons)

The ‘mailed horsemen’ of Persia

The expansion of Rome into the Near East brought them into conflict with one of these nations, the Parthians, who were also the successors of the Seleucids. Thanks to the Roman historians who wrote about the conflict between Rome and Parthia, we have a certain amount of knowledge about the cataphract. Ironically, perhaps, is that one of the best descriptions of the cataphract is to be found in a novel, and not a historical work. In Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, the cataphracts, or “mailed horsemen”, are described as “the most valiant of all the Persian fighters”, and that each of them looked like “a man made of iron or a statue fashioned with hammers”. Heliodorus also provides a detailed description of the cataphract’s armor: a closed helmet covered the warrior’s head down to the shoulders, leaving only two holes for the eyes (Ammianus Marcellinus, a 4 th century Roman historian, adds that the helmets were fitted with “forms of human faces”); a coat of mail made of brass or iron scales protecting the entire body of the warrior; the horse is similarly armed. As for weapons, the warrior wields “a great staff, bigger than a spear”, and a sword.

A stone-etched relief depicting a Parthian cataphract fighting against a lion. Housed in the British Museum. (Wikimedia Commons)

The charge of the cataphracts

Generally, the cataphract is used to charge en masse into enemy lines. Due to the sheer weight of their armor, a cataphract charge can deal a great blow to the enemy. The impact of a cataphract charge is also highlighted by the historian Tacitus, who wrote that “when they (the Sarmatians) attack the foe on horseback, hardly any line can resist them.” The irresistible force of a cataphract charge may also have a psychological effect on their enemies, as another historian, Cassius Dio, suggests. In his account of Crassus’ defeat at the Battle of Carrhae, Dio claimed that “many died from fright at the very charge of the pikemen”. The reputation of the cataphract is further enhanced by the statement (in Heliodorus and Plutarch) that their charge had enough force to impale two men in one go.

The charge of the cataphract put much fear in the enemy. Equestrian Relief at Firuzabad Iran showing Cataphracts dueling with lances (Wikimedia Commons)

The dangerous life of a cataphract

Nevertheless, the cataphract was not invincible. Its greatest strength was also its greatest weakness. For a start, the weight of the armor was so great that the warrior needed others to help him up onto his horse. As long as he remained on his horse, the warrior was in a safe position. If he was dismounted during battle, however, he would have been an easy target for the enemy. Although the armor afforded extra protection, it also reduced the horse’s stamina. Furthermore, overheating was also a major problem. These weaknesses were exploited by the Roman emperor Aurelian during his battle against the Palmyrenes led by Zenobia. Using his lighter cavalry, Aurelian provoked the Palmyrene cataphracts to attack. The emperor’s cavalry, however, were ordered not to engage the cataphracts, and pretended to retreat. Once the cataphracts succumbed to the heat and the weight of the armor, Aurelian’s cavalry charged and annihilated the Palmyrene cataphracts. Whilst the armor of the cataphract was able to withstand attacks from swords and arrows, they seemed to be useless against blunt weapons. During Aurelian’s battle against the Palmyrenes, he had troops from Palestine armed with clubs and staves that were used specifically “against coats of mail made of iron and brass”.

A depiction of Sarmatian cataphracts fleeing from Roman cavalry during the Dacian wars circa 101 AD, at Trajan's Column in Rome (Wikimedia Commons). One man has fallen from his horse, the greatest danger for a cataphract.

Despite the weaknesses of the cataphract, they were still a very formidable cavalry unit. This is perhaps best seen in the fact that they were first adopted by the Seleucids, and then by the Romans. Additionally, the Sassanians and the Byzantines, the successors of Rome and Parthia respectively, also employed the cataphract in their armies. With increasingly sophisticated armor being produced by the blacksmiths of Medieval Europe, the cataphracts were no longer the feared force they once were, and over time they eventually became obsolete.

While you may not be into gaming, there are several recently released games that provide an accurate look at cataphracts and their operations, including Rome II: Empire Divided and Mount & Blade 2. In both games, the cataphracts are represented as heavily armored riders and horses, and are used to making charging attacks against enemy lines.

Featured image: ‘The Parthian cataphract’. (Total War game picture and retouched with Photoshop / Manu56bzh).

By Ḏḥwty

References

Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman Antiquities [Online]

[Rolfe, J.C. (trans.), 1939-50. Ammianus Marcellinus’ Roman Antiquities.]

Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Ammian/home.html

Cassius Dio, Roman History [Online]

[Cary, E. (trans.), 1914-27. Cassius Dio’s Roman History.]

Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/home.html

Heliodorus, Aethiopica [Online]

[Underdowne, T. (trans.), 1587. Heliodorus’ Aethiopica.]

Available at: http://www.elfinspell.com/HeliodorusTitle.html

Invictus, 2006. Cataphracts and Clibanarii of the Ancient World. [Online]

Available at: http://allempires.com/article/index.php?q=cataphracts

Plutarch, Parallel Lives: Crassus [Online]

[Perrin, B. (trans.), 1916. Plutarch’s Parallel Lives: Crassus.]

Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Crassus*.html

Shahbazi, A. S., 2015. Parthian Army. [Online]

Available at: http://www.iranchamber.com/history/parthians/parthian_army.php

Tacitus, The Histories [Online]

[Moore, C. H. (trans.), 1925-37. Tacitus’ The Histories.]

Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Tacitus/home.html

www.hellenicaworld.com, 2015. Cataphract. [Online]

Available at: http://www.hellenicaworld.com/Byzantium/Military/en/Cataphract.html

Zosimus, New History: Book 1 [Online]

[Anon. (trans.), 1814. Zosimus’ New History: Book 1.]

Available at: http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/zosimus01_book1.htm

Comments

It wasn’t the Parthians per se who originated the Cataphract. It was the nomadic but powerful tribes of Royal Scythia, Massagatea and Roxolani (who were also of Persian extraction). They populated the lands of the caucasus’s and modern day western Russia. From them the Parthians learned the concept of Cataphract horses which in turn was employed by the Greek Seleucid kingdom. The Greek Bactrian kingdom also made great use of Cataphracts to do battle with the Persians.