The Gory History of Barber Surgeons: Medieval Medicine Gone Mad

It’s no surprise that the history of medicine had a rocky and somewhat gruesome journey before reaching its current, modern state. From the earliest meddling in surgery in Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages and a much more brutal and crude way of dealing with illness and injury, medicine wasn’t always so beneficial. And this fact becomes clearer when we consider the role of barber surgeons.

Barber surgeons were the usual medical practitioners through much of the Middle Ages, tasked with everything from bloodletting, amputation, leeching, pulling teeth, and, of course, the everyday duties of cutting beards and hair. It sounds efficient, right? While you get your arm sawed off, you can get a haircut too. But it certainly wasn’t pleasant to be afflicted in the Middle Ages.

From Haircuts to Amputations – How Barber Surgeons Emerged

From as early as 1000 AD, the role of surgeons and physicians was curiously separated. The surgeons were often catering to the lower class, while physicians resided in courts and castles. The latter only observed the afflicted – they considered themselves above the practice of surgery, and instead observed the patients.

Physicians would spot the symptoms, injuries, and afflictions, and offer their counsel accordingly - relying on their academic knowledge to suggest the course of treatment. They would also be found almost exclusively in the service of the wealthy, where they would treat the royal and aristocratic families and their knowledge was held in high regard. These physicians studied in Latin and fluently spoke it, they were considered highly educated, and as such, the practice of surgery was considered beneath their dignity.

- The Celestial Monsters and Demonic Wizards Of The French King’s Surgeon, Ambroise Pare

- Five Bloodcurdling Medical Procedures That are No Longer Performed … Thankfully

But what of the other classes? The soldiers, peasants, monks and workers? In their lives, injuries and afflictions were commonplace, more so than with the nobles. And as the physicians were loath to get their hands dirty, someone had to – the barber surgeons.

‘The Surgeon’ by David Teniers the Younger, 1670s. (Public Domain)

While the physicians, mostly in the 15th century and onwards, were accredited and licensed by the universities in which they studied, barber surgeons on the other hand, were not. They had to apply to the trade guild and would subsequently become apprentices to barbers. This apprenticeship was often difficult, rough, and mixed up – it covered a range of services, although it was connected with barbers.

Over time the term barber surgeon was born –and the basic service of a barber gained many other tasks.

An average surgeon that was trained in one of these guilds was tasked with a variety of “healing” tasks that physicians wouldn’t do. The surgeon was expected to deal with basic wounds and lacerations, with burns and skin rashes, setting fractured bones and dislocated limbs, venereal diseases, lancing infections, topical applications, and applications of poultices. The more skilled surgeons would also perform demanding procedures including trepanation, amputation, cauterization, and delivering babies.

Ambroise Paré, as an apprentice barber-surgeon in a busy shop in Paris. Wood engraving by E. Morin after J. Ansseau. (Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0)

And the barber surgeon arose as a more lowly form of a true surgeon –essentially an apprentice. They were tasked with more basic procedures, and tasks that were slightly more gruesome and dirty. Besides fetching and assisting, a barber surgeon would deal with bloodletting, leeching, cupping, and pulling out teeth. As time progressed, barber surgeons – the apprentices –became increasingly independent, and eventually became competition for proper surgeons.

The earliest and most basic roles of barber surgeons were connected to monasteries. Even as early as 1000 AD they would be employed, through guilds, by the numerous monasteries around Europe. The main reason for this was actually because of their barbering skills. They were on-hand to cut the monks’ hair regularly, as they needed to be tonsured. Tonsuring is the religious practice of shaving the top of the head.

St Bartholomew (1473) by Carlo Crivelli. (Public Domain)

But in time, the barbers were allowed to do more than just cut hair in the monasteries. In fact, cutting hair was done in their spare time. As monasteries took on the role of hospitals and sanctuaries, especially in France and Germany of the Middle Ages, barber surgeons took a real medical role. Hair cutting went on to bloodletting, and bloodletting to setting limbs, and eventually came amputation and everything in between.

When a law was passed in 13th century France which required all physicians in training to swear an oath not to perform surgery, it effectively paved the way for barbers to take up the vacant space, often learning as they went. Which didn’t bode well for the poor and soldiers.

A barber surgeon’s bloodletting set, beginning of 19th century, Märkisches Museum Berlin. (Anagoria/CC BY 3.0)

Leeches, Limbs, and Loose Teeth

With the rise of urban areas – towns and villages – the need for medical assistance grew. And soon physicians were outnumbered by surgeons. They had the learning, but surgeons had the hands-on approach.

To protest the physicians and their restriction of practicing surgery, a special college was created in 1210 at St. Côme. It was established and run by Jean Pittard and was the first step towards the later emergence of the guilds. The surgeons at St. Côme were separated into two classes – the long and short robes. The long robes were the proper, established master surgeons, while the short robes were the apprentices –the barbers in training.

- The Ugly History of Cosmetic Surgery

- Archaeologists Search for Neolithic Home of Avebury Stone Circle Builders Between the Monuments

Anatomical Theater of the Paris Academy of Surgery in 1694. (Public Domain)

By 1371 in France, barber surgeons paradoxically surpassed master surgeons. This happened because physicians saw the rising influence of master surgeons and tried to stifle it by once again giving headway to those who were less-educated. And so in 1371 the French king proclaimed his own barber as the head of all barbers and surgeons of France.

And about seven decades before that, in 1308, King Edward II of England granted the barbers guild status and they played a major role in Britain of the time. Afterwards, in 1375, this guild was further established and separated into two distinct roles – those who did surgery and those who were only barbers.

A proclamation was also made that required all surgeons to be licensed by the Crown in order to perform their services. And in Glasgow, under James the VI, all apothecaries, surgeons, barbers, and barber surgeons were united under one charter - but they were dominated by the majority of barber surgeons.

The role of barber surgeons became increasingly associated with more gruesome surgical procedures when their services were employed in wars. They were prominent when Henry V undertook his campaign in France in 1415, as well in the Thirty Years’ War from 1618 and 1648. Wars would bring a lot of work for budding barber surgeons, when they were on-hand to amputate, suture, stitch, and cauterize. But in peace time, these gruesome tasks were performed rarely, and so, in order to earn a living, the barber surgeons would shift to their barber role, cutting hair for a living.

When their services were needed, they were indeed many and very…colorful. A barber surgeon’s roles were diverse and in time they gained more importance than simply crude pseudo-medicine. One standard concept of their practice was the so-called humorism.

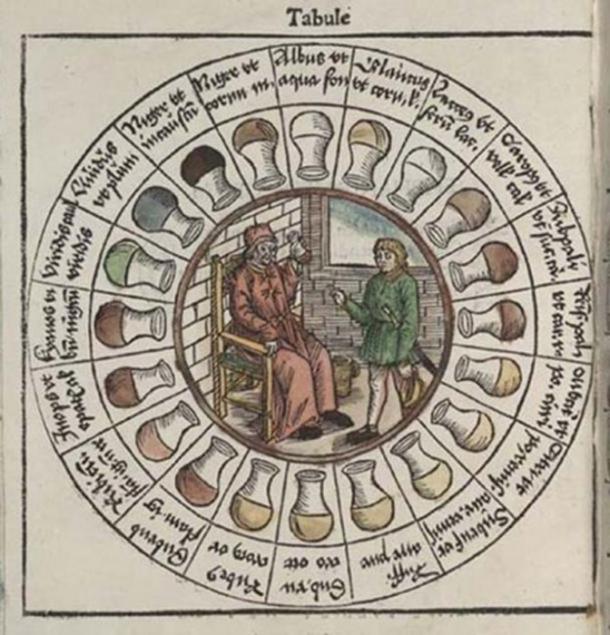

Alchemic approach to four humors in relation to the four elements and zodiacal signs. (Public Domain)

This system of medicine survived from Roman and Greek medicinal practices and revolved around four “chemical systems” that regulated human behavior and health. These four temperaments were: sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic. Barber surgeons continued the practice in the Middle Ages.

They would almost always examine the patient’s urine in order to determine their affliction via a chart. Based on the color, consistency, and the taste of the patient’s urine, the barber surgeon would proceed with treatment. One of the most common “remedies” was bloodletting. It was believed that through removal of blood, the surgeon would also remove the bad “humors” from the body.

A Medieval urine wheel. (OnlineRover)

In the early medieval period, this practice was usually performed with leeches. In fact, this was such a popular method that it nearly drove leeches to extinction. As methods evolved further, barber surgeons used a specialized tool that helped them open an incision in the patient’s vein and carefully extract up to a pint of blood from a person.

Bloodletting was a common procedure and remained in heavy use all the way up to the 18th and 19th centuries. But the truth is that only on rare occasions would it be beneficial. And a beneficial effect was only a temporary feeling, as the loss of blood would reduce blood pressure. In fact, bloodletting was usually harmful to patients.

Amputation, Trepanation, and No Anesthetization

Amputations were another common procedure that barber surgeons performed, and with highest frequency in war. The procedure was disliked by the patients, for obvious reasons, but mostly because of the lack of anesthetics.

The same went for the procedure of trepanation, which was also quite common. It constitutes a hole being bored into the skull of the patient, exposing the outermost layer of the protective membrane of the brain and the central nervous system. It was believed that drilling the hole would alleviate different ailments and release pressure. It was considered a cure for seizures, skull fractures, and different behavioral problems. Early on it was believed that drilling a hole in the skull would allow demons and evil forces to escape.

‘The Extraction of the Stone of Madness’ (The Cure of Folly) by Hieronymous Bosch. (Public Domain)

The Decline of the Barber Surgeons

As time went on and surgery gained a more refined and important aspect, barber surgeons quickly became phased out. This was directly caused by surgery shifting from a craft to a profession. One of the first steps towards the diminishing of barber surgeons occurred in France, when surgery got a boost under the rule of Louis XIV.

His grandson, Louis XV, would further this when he established five chairs of surgery at the college of St. Côme. And finally, in 1743, every barber and wig maker in France was forbidden to perform surgery. Two years later, barbers and surgeons were completely separated in England as well.

- Medicine Maidens: Why Did Women Become the Primary Medical Providers in Early Modern Households?

- 9 Ancient Physicians and Legendary Healers that Changed Medicine Forever

A barber-surgeon extracting stones from a woman's head; symbolizing the expulsion of 'folly'(insanity). Watercolor by J. Cats, 1787, after B. Maton. (Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0)

When we take the early medicinal and surgical practices into account, we can easily cherish what we have today. It is clear that the dated Roman and Greek practices were awfully misplaced in Medieval times and medicine suffered from stagnation. But the ones who suffered the most were the patients –the afflicted who were completely clueless about the workings of their bodies. Pain was a part of life for them, and the barber surgeons were considered healers, but they generally weren’t.

It also gives us an insight into the class divide of our past, when the nobility and the poor were hugely separated. But when it came to surgical procedures, this divide was partly erased because when the barber surgeon whipped out his trepanning drill or his trusty amputation saw, all men were seen as one – just flesh and blood.

Top Image: Surgical instruments of ancient physicians. Credit: Kai Beercrafter / Adobe Stock

References

Elmer, P. 2004. The Healing Arts: Health, Disease and Society in Europe, 1500-1800. The Open University, Manchester.

MacDonald, F., Geyer-Kordesch, J. 1999. Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow – The History of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, 1599-1858. The Hambledon Press.

McCallum, J. 2008. Military Medicine – From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. ABC Clio

Comments

Hi Ms. Aleksa Vučković, I enjoyed very much reading your article. I saw that you your information from very important sources but if you like novels, I would recommend you to read "The Physician" by Noah Gordon. Yours Naum

Very interesting article thank you