The Great Stink of 1858: When the Thames River was Filth and Excrement

What happens when we stop taking care of our surroundings? Humans create a lot of waste, and it needs to be disposed of adequately. Neglecting to do so can only lead to trouble. Londoners living in 1858 had a first-hand experience of what happens when waste is not treated properly. The event known as the “Great Stink” was everything talked of in July and August of 1858. The extremely hot weather transformed the capital city of England into a great stinking mess. The main problem was the improper disposal of human waste, which almost all flowed directly into the Thames River. Disgusting, unethical, and straight out unhealthy, this problem caused a lot of issues for citizens of that vast city. So how was the “Great Stink” resolved?

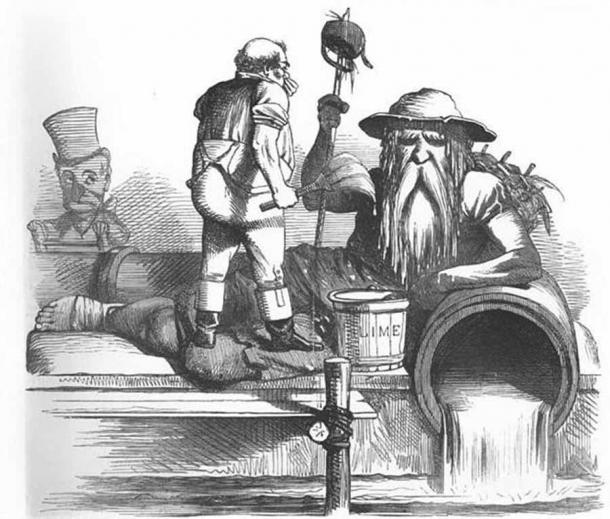

Death rows on the River Thames claiming the lives of victims who have not paid to have the river cleaned up during the Great Stink of 1858 in London, England. (Punch Magazine / Public domain)

What Led to the Outbreak of the Great Stink?

Ever since the medieval period, great cities and metropolises faced an increasingly growing problem. And that problem was the treatment of waste. In an age where technology had its limitations, it was a big challenge to effectively dispose of waste created by thousands of humans inhabiting a single “space” i.e., a city. London, ever since the Roman times, was known as one of the largest cities on earth, and one of the earliest metropolises. This meant that waste treatment was always a problem for civilization from the start. In the Middle Ages, hygiene was not a priority. Human waste was openly disposed of, often through windows of residential homes. Accounts tell us that rivers of human waste flowed through ditches and man-made channels that bordered streets. Even before that, it was a well-known fact that privies, medieval toilet rooms, had no pipes. They simply ended in mid-air and the human excrement fell down to the ground or another roof or something else.

- Fighting the Flaming Wrath - The Great Fire of London, 1666

- The Forgotten History of the London Stone, an Artifact Linked to Aeneas, King Arthur, and John Dee

During these times, there was a special career in London called the “night soil” collector. This job was reserved for the lowest of the low, men who were willing to do anything for a bit of money. Night soil, of course, was the term for human excrement: people usually had “close stools” or chamber pots in which they did their “business.” And when the morning came, collectors came to dispose of this “night soil” in their carts. It was unhygienic to say the least. Ever since medieval times, night soil collectors were known as “gold finders,” since it was believed that gold could be found among the excrement of influential nobles (which fell down from castle privies).

Still, dumping all that waste was a problem. Night soil collectors used the excrement they gathered to fertilize farmland, but even that was not enough of a solution. Naturally, the next best thing was directing all the filth to the nearest river or stream or both. And in London the River Thames was a perfect sewage system until it wasn’t. Running as the heartline of London, it was available to all. And waste soon began flowing freely into it. By the mid 1800’s however, the waste that was “alive” in the river was hundreds of years old. Since the 1600’s and before, dealing with waste was done on an “out of sight, out of mind” basis. But it was becoming apparent that this was not a sustainable solution for a huge city like London in the mid-19th century.

Father Thames introducing his “children,” diphtheria, scrofula and cholera, to the fair city of London. (John Leech / Public domain)

In Desperate Need of a Healthier Solution

In 1858, the centuries’ old problem became critically apparent. After receiving foul human waste for centuries, the River Thames could take it no more. In fact, it was not a river anymore. It was an oozing, diabolical, unbelievable flow of hellish fluids. In the summer of 1858, the heat literally boiled up all that filth, and the Londoners became aware of the problem that they helped create. It came to the point that one simply could not pass beside the river without feeling ill. The Thames literally abounded with oozing fluids composed of human excrement, industrial waste, animal carcasses, rubbish, dead fish, muck, and who knows what else. It was so foul that the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Benjamin Disraeli, famously said:

"That noble river, so long the pride and joy of Englishmen, which has hitherto been associated with the noblest feats of our commerce and the most beautiful passages of our poetry, has really become a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors. The public health is at stake; almost all living things that existed in the waters of the Thames have disappeared or been destroyed; a very natural fear has arisen that living beings upon its banks may share the same fate; there is a pervading apprehension of pestilence in this great city."

A solution was necessary and fast. The crisis surrounding the foulness of the Thames was made all the worse with the three concurrent outbreaks of cholera prior to 1858. They claimed many lives and were all blamed on the infernally unhygienic state of the river. The first outbreak of cholera in London appeared in 1832, reaching the city from Sunderland. This first outbreak claimed some 20,000 lives across Britain, and around 6,536 in London alone. The second cholera outbreak appeared in 1848, this time claiming more than twice as many lives as the previous outbreak. The third cholera pandemic of occurred in 1853-1854. London suffered immensely, with 10,738 lives being lost. Undoubtedly, much of the loss of life had to do with the poor sanitation and the foulness of the Thames.

During these outbreaks, impoverished people living close to the river were in dire need of help. They wrote directly to the “Times” newspapers, pleading for a solution:

“We live in muck and filth. We aint got no privez, no dust bins, no water splies and no drain or suer in the whole place. If the Colera comes, Lord help us.”

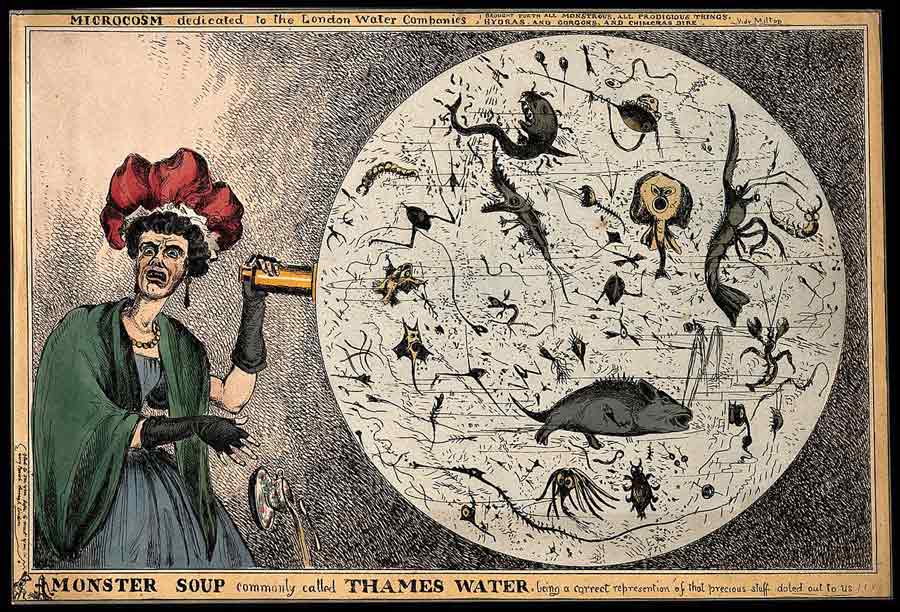

One method Londoners tried during the Great Stink was added lime to the filthy water entering the River Thames but too much lime would have been required for this to work! (Punch Magazine / Public domain)

No Sanitation and No Quality of Life for Impoverished Londoners

With this, the issue of river pollution became a national issue and was not just a London problem anymore. Citizens across Britain were well aware of the issue at hand, since other cities had similar problems. It was noted that Glasgow was “possibly the filthiest and unhealthiest of all British towns”, where it was predicted that 50 percent of children would never reach the age of five. With all this considered, the government realized that it was nigh time to finally solve this issue once and for all. A critical solution to sewage disposal and water supply was essential and urgent.

- Cabman’s Shelters: A Place for Cold London Cabbies and Maybe Jack the Ripper

- Beaten to Death for Littering with Eel Skins: ‘Murder Map’ Reveals Medieval London’s Meanest Streets

The public, of course, was the most vocal supporter of the needed solutions. The public gathered around the noted English chemist and physicist, Michael Faraday, who was proposing a complete reformation of the “toxic river.” To demonstrate his cause to the public, he took a boat ride across the stinking river of filth and carcasses, observing what he experienced. This he penned down in a letter to the government, which would soon become the rallying point for the stricken public. Faraday wrote that the Thames was “an opaque pale brown fluid” and that it was nothing more than “a real sewer.”

In the early 1850s, Joseph Bazalgette, a consultant engineer in the railway industry, working under the chief engineer, Frank Foster, began to develop a more systematic plan for the London's sewers, which were ready for installation by 1856. (Lock & Whitfield / Public domain)

A Last Moment Solution for Stricken London

It soon became apparent to all that London could not experience another hot summer: Thames was a source of death. Luckily, the combined public pressure and the unbearable stench that threatened even the Palace of Westminster, finally urged the Parliament to act on the matter. In just 18 days, they created a bill, passed it, and signed it into law that would completely “refurbish” the whole of the affected river. Still, many criticized the apparent “last minute” decision by the Parliament, suggesting the theory that they only created the law once the stench encompassed their wealthy homes.

“In 1855 the condition of the Thames appalled the eminent scientist - but three years later, in 1858, the hottest summer on record reduced it to a state in which it offended a more influential body: the politicians whose recently rebuilt houses of Parliament stood upon its banks. This proximity to the source of the stench concentrated their attention on its causes in a way that many years of argument and campaigning had failed to do and prompted them to authorize actions which they had previously shunned.”

But either way, the timeless River Thames was finally receiving the care it so desperately needed. After centuries of improper waste disposal, London was to receive a modernized sewage system. This hefty task, one of the biggest industrial undertakings in the history of London, was given to the noted English civil engineer, Sir Joseph Bazalgette.

Joseph Bazalgetteman came up with an ambitious and modern plan. His new sewage system of London was to stretch across an imposing 1,100 miles (1,800 km) and would travel both below and above the streets. Another challenging part of constructing the sewers was the creation of two embankments: Chelsea and Victoria. Their creation was a major feat of civil engineering. With these two embankments, Bazalgette managed to reclaim the marshy, polluted areas on the side of the Thames and to also create the drainage for the sewage system. The cost of building the embankments was estimated at around £1.71 million, making it one of the costliest undertakings in the history of London. The creation of the sewers took several years, and Bazalgette stated that it was one of the most challenging undertakings he ever faced.

A cross section of the Thames Embankment in 1867, showing the sewers running next to the river side. (Wellcome Images / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sir Bazalgette Achieves the Impossible!

Today, this sewage system is still in use in London, making it around 150 years old. But it was done in such a way that it is still quite effective. Of course, the Londoners were the ones to benefit most from the construction of the better sewage. They were once more given a chance to breathe in fresh air, without any stench, and to live beside a river that was not a health hazard.

Over time, the River Thames “cleaned itself” and healed its wounds, becoming one of the cleanest rivers in the world. Today it houses around 125 species of fish and 400 species of invertebrates. Still, many argue that the river is still not completely “swimmable,” and those who attempt it may still get the so-called “Thames Tummy” characterized by sickness and high fever.

After all, the Thames still receives London’s raw sewage. It is routinely pumped out into the river during heavy rains, especially since Bazalgette constructed the system in such a way to facilitate the mixture of sewage and rainwater. And when the sewage system overfills, it is pumped into the river through 57 sewer overflows. It is estimated that around 39 million tons of mixed sewage (waste and rainwater) is dumped into the river annually.

A picture of the back of the Thames Tideway Tunnel Boring Machine Rachel named after Rachel Parsons. The machine is 90 meters or 295 feet long. The image shows the shaft down to the Thames Tideway Tunnel, the tunnel opening, a smaller tunnel connecting to another site above and a crane moving material down to the machine. (MyrtleGal / CC BY-SA 4.0)

A Nature That is No Longer What it Was

Luckily, London is about to receive some much needed reinforcements. Currently, a 16 mile long (26 kilometers) “super sewer” is being constructed. It is known as the Thames Tideway Tunnel, and it is currently under construction at 24 separate sites that run from Acton in West London all the way through Beckon past the Thames Barrier. This highly modern sewer is bound to solve some of the remaining pollution problems. Given the price of the overall project, nearly 6 billion euros (6.78 billion dollars), you can understand how massive this dream is. The date of completion for the new system is 2024.

- Forgotten Disaster: The Great London Beer Flood That Killed Eight People

- The Prophecy Of The Tower Of London Ravens: Less Than Six Means Doom

After all, the case of the river Thames and its “Great Stink” is a great lesson for all of us. It tells us that human waste, left out in the open, can be a great threat to the health of all. Luckily, medieval times are long gone, and sewage and sanitation are quite modern in most of the places in the world. But still, there is room for improvement.

The great rivers of the world—the Thames, Danube, Ganges, Neva, Niger, and others—are all in dire need of cleanliness and hygiene. Their original pristine conditions have been long lost. Today they are hazy, muddied, and smelly, displaying a 21st century perversion of what was once untouched nature.

Top image: A 19th-century woman during London’s Great Stink woman drops her teacup in horror upon viewing a magnified drop of polluted Thames River water, which was a prime source of water-borne diseases such as cholera and typhoid. Source: William Heath / Public domain

References

Ackroyd, P. 2008. Thames: Sacred River. Vintage.

Bibby, M. 2022. London’s Great Stink. Historic UK. Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Londons-Great-Stink/

Burns, J. 2018. Too hot? In 1858 a heatwave turned London into a stinking sewer. BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/education-45009749

Halliday, S. 2001. Death and Miasma in Victorian London: An Obstinate Belief. BMJ.

Lemon, J. 2022. The Great Stink. Cholera and the Thames. Available at:http://www.choleraandthethames.co.uk/cholera-in-london/the-great-stink/

Comments

This was the situation in all cities everwhere before the mid-19th century. Paris, for example, was the centre of the French tanning industry in the 15th century. That city alone was dumping the carcasses of hundreds of thousands of animals a week into the Seine River, plus the chemical residues from the hundreds of fullering businesses. That’s not to mention the herds of livestock driven daily into the city and the household wastes of a population of about 150,000 in 1500.

All too often people have a romantic, idealized notion of what life was like in pre-industrial times. Truth was, they were filthy, disease-ridden, violent and short. Typical affluent life expectancy was much less than 40.

And it was coal and oil which put an end to this cycle of premature death, disease and misery.

I love Pete Wagner's comment. The sentence..But there is still room for improvement.. is spot on. If you think where you live has this under control. I challenge you to do that research. The bigger the city, the bigger the problem. And it all flows to the oceans of the earth. Worse yet, sanitation departments only remove the solids to quietly truck to farmers willing to use it on fields. That's called treatment. Today the scarry part is the pharmaceutical, hormonal, heavy metal, and other toxic chemical components dumped on soil for crops. The ammont of plastic is disturbing. Nearly all soaps and cosmetics are full of micro-beads of plastic. Science is showing plastic doesn't decompose, it only reduces to smaller size. Micro beads are to small already to see or feel. These end in oceans and only get smaller as they pass through progressively smaller life forms. Floating islands of plastic are only the destruction we can see...now. However there are solutions. But like the scientist in the article, it's not cheap, easy, or immediate. Ironically, carbon is our friend in this solution in many ways. Just so you know, archeologists discovered ancient indigenous peoples in the Amazon River basin created the Terra Preta soil that became the rainforest. A people who didn't have the power of the wheel or horses, knew how to use manure and charcoal to help the planet.