Aeons of Battle: The 5 Longest Wars in History

In the annals of humanity there is one phenomenon that has consistently weaved and threaded itself through the fabric of time. It is, of course, war, which from the very earliest times until the modern-day continues to destroy, pillage, kill, and generally plague the human race’s best efforts of lasting worldwide peace and cooperation. With the technological advances of the 20th century, the impact of war has become even more devastating and costly, in more ways than one.

As a result, modern conflicts are often a lot shorter; the two most destructive wars of the 20th century, World War One and World War Two, for example, only had a combined length of 10 years. Wars in the modern-day are usually brief; a blink in a person’s lifetime. Before the modern era however, and before the onset of the mechanical pandemonium which characterizes battle today, wars had the capability of lasting several lifespans, as the five longest wars in history demonstrate.

The Varus battle by Otto Albert Koch, 1909. (Public domain)

5. Romano-German Wars

Following Rome’s destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, the republic experienced a period of relative stability in the following decades. This ended in 113 BC, with the incursion of the Germanic tribes of Cimbri and Teutoni at Noricum, in modern-day Austria. In 105 BC the Germans invaded Gaul, attempting to make alliances against the Roman Republic. In that same year, at the Battle of Arausio, the legions of the Roman commanders Quintus Servilius Caepio and Gnaeus Mallius Maximius were annihilated by the invaders, causing widespread panic to fester around the realm.

However, with the rise to power of legendary Roman General Gaius Marius, who became Roman consul for five consecutive years from 104 BC, the German danger was quelled by a series of victorious skirmishes. In 102 BC Marius marched on the Teutoni tribes who were occupying southern Gaul with six legions comprising of 40,000 men, following them to Italy where he finally defeated them, allegedly killing 100,000 and taking 60,000 of the fallen foe as prisoners.

- The Real Game of Thrones: Enduring Saga of the Hundred Years’ War

- The Peloponnesian War: Intrigues and Conquests in Ancient Greece

The next major engagement, at the Battle of Teutoburg in 9 AD, however, ended with crushing Roman defeat. Following the conquest of Germania in 12 BC, Roman Emperor Augustus ordered his successor, Tiberius, to fully Romanize the German provinces. Angered by the taxes imposed on them by the Romans, German chieftain Arminius plotted a rebellion against the Roman governor, Publius Quinctilius Varus. In 9 BC, the Germans devastatingly ambushed the legions stationed on the frontier, capturing their Roman standard and killing 20,000 soldiers. Varus was so ashamed he fell on his sword shortly after the decimation of his armies.

In the following years up to 410, the Romans and Germans fought frequently with a varying degree of success. In 165 to 180, for example, during the Marcomannic Wars, the Germans managed to invade parts of the Roman empire which was severely weakened by the rise of the deadly Antonine plague, but the Romans were able to conquer regions of Germany in 278, under Emperor Probus and in 357 under Julian the Apostate.

In 410, however, Rome was mortally weakened by the sacking of Rome by Visigothic chieftain Alaric and 40,000 of his men who plundered and pillaged the ancient capital. This cataclysmic event seriously destabilized the empire, and was finished off in 476 when it fell to a German warlord called Odoacer, who ousted the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, and proclaimed himself as king over Roman dominions. The Romano-German Wars came to a close with the Lombard invasion of Italy between 568 and 572, in which the Lombards of Germania led by Alboin took Italy from the ailing Byzantine empire that had replaced the classic western Roman empire. In total, the Roman-Germanic wars lasted for 685 years.

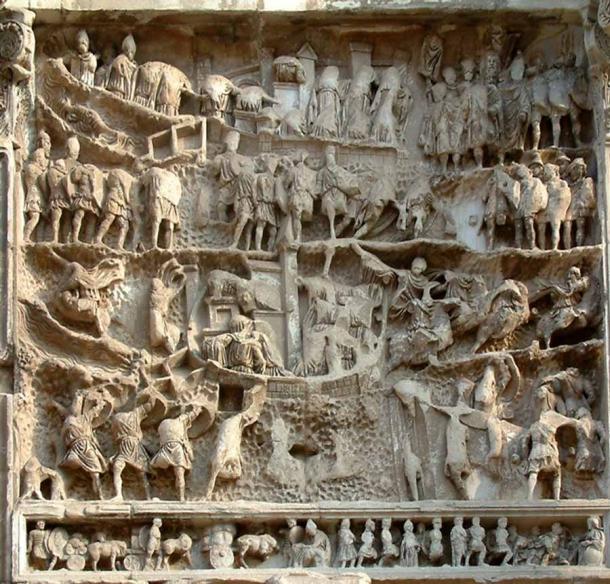

Relief of the Roman-Parthian wars at the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

4. Roman-Parthian Wars

The first Roman-Parthian War happened between 74 and 62 BC, after the Roman annexation of Armenia motivated the Parthians to put a stop to the expansionist aims of their western adversaries. In 55 BC, dreaming of a Roman presence in Syria, Marcus Licinius Crassus embarked on an ambitious campaign against the Parthians. The overconfident Romans were defeated by the Parthians who took the Roman standard and beheaded Crassus, allegedly pouring molten gold into the mouth of his decapitated head.

Following an unsuccessful attempt to win back the Roman standard by Mark Anthony in 36 BC, Emperor Augustus decided to settle the issue in 20 BC through diplomacy by putting a pro-Roman monarch on the Armenian throne, establishing peace for over a century.

The Roman-Parthian wars were reignited in 113 AD by Emperor Trajan who mounted a formidable offensive against the Syrian enemies who had deposed the pro-Roman ruler of Armenia in favor of their own puppet king. Trajan successfully conquered Armenia and parts of Iraq, helped in large part by a declining Parthian empire unable to defend itself against the 11 Roman legions. However, revolts in the newly acquired territories in 116 forced Trajan to retreat, with the following emperor, Hadrian, abandoning the Parthian conquests and brokering peace with the enemy once again, resuming the client kingdom status of Armenia.

After frequent Roman incursions into Parthia in 165, 198, and 199, the Middle-Eastern kingdom experienced a revival of fortunes in 227 with the rise of the Sassanid dynasty, who swiftly moved to re-capture Parthian losses in Roman Syria between 241 and 272. In 260, Roman emperor Valerian was captured by Sassanid monarch Shapur I, who supposedly used his illustrious prisoner as a foot-stool to mount his horse before flaying him alive after years of captivity.

Rome's fortunes recovered in 298 when Sassanid King Narses was humiliated by Roman commander Galerius, who re-captured northern Mesopotamia and established the Roman city of Nisibis. In 336, Nisibis was taken by the Sassanids after a naive foray into Sassanid lands by Emperor Julian turned disastrous, ending in the loss of Roman territory instead of acquisition.

The conflict flared up again in 502, when conquest-hungry Sassanid rulers Kavad and Khusro I retook Roman territories in Persia after they were stripped of defenses following Emperor Justinian’s effort to repossess Roman regions in Spain, Italy, and North Africa. In the last act of the wars, Khusro II, taking advantage of a succession feud in the Byzantine empire, recovered Armenia, Anatolia and Egypt during his reign between 590 and 628, which, apart from Armenia, largely remained Muslim territories up to the present day. The Roman-Persian hostilities were the longest wars of the Romans, clocking in at 702 years.

Illustration from the Manasses Chronicle depicting (above) a feast in Constantinople in honor of Simeon I and (below) a Bulgarian attack on the Byzantines, during the Byzantine-Bulgarian Wars. (Public domain)

3. Byzantine-Bulgarian Wars

Decades after the Parthians, the Bulgarian empire, founded in 680 AD, would become Byzantine Rome’s main antagonist in the Balkans after their victory over imperial forces in 681. In combination with local slavic tribes, Bulgarian leader Asparukh took over the north-eastern reaches of the Balkans, forcing the Byzantine Empire to recognize their power, and over the next centuries, many wars and alliances would be made between the two great realms.

In 717, at the Second Siege of Constantinople for example, the Byzantines were saved from pillage by the Bulgarians who swept in to launch a surprise attack on the armies of the Umayyad Caliphate. Equally, the Byzantines, who held a strong cultural sway on the Bulgarians, helped introduce Christianity in 864.

However, cooperation was rare, and between 807 and 811 the Bulgarians would once again invade, this time under the rulership of King Krum, killing Byantine emperor Nikephoros and fatally wounding his son-in-law, Staurakios with a wound to the neck. Following Krum’s death in 814, an 80 year period of peace was established, only to be broken by Bulgarian monarch Simeon I in 894 whose forces were repelled by the Byzantine navy which sailed up the Black Sea to attack the Bulgarian rear. Eventually however in 896 the Byzantines were quashed at the Battle of Boulgarophygon and forced to pay tribute to the Bulgarians.

By 971 the situation had changed and Bulgaria found itself in a diminished state after unsuccessful wars with Russians, Croatians, and Maygars. Sensing weakness, Byzantine overlord John I Tzimiskes launched an invasion, turning the century-old enemy into a subordinate, and by 1018 the whole of Bulgaria was in Byzantine hands following Emperor Basil II’s momentous victory at the Battle of Kleidon in 1014.

In 1185, after failed revolts in 1040s, 1070s, and 1080s, the Bulgarians finally escaped from Byzantine shackles, once again becoming independent thanks to the leadership of Theodore Peter and Ivan Asen and the enfeebled state of Byzantium which was unable to mount a strong defense. After being officially recognized as independent in 1187, battles for Balkan supremacy continued up to 1396 when all of Bulgaria was taken by the emerging Ottomans of Turkey. By 1453, when the Turks had captured Constantinople, both Byzantium and Bulgaria had been assimilated into the empire, finally ending the Byzantine-Bulgarian Wars, which lasted 715 years.

15th-century depiction of the Siege of Orléans of 1429, the French royal army’s first major victory at the later stages of the Hundred Years’ War. (Public domain)

2. Anglo-French Wars

The Anglo-French wars were kick started by the conquest of England by Duke William of Normandy in 1066. Thanks to the 1002 marriage between King Athelred of England and Norman princess, Emma, William the Conqueror, as he is most famously known, held a claim to the English throne which he usurped after defeating Harold Godwin at the Battle of Hastings. For the next 150 years his family would rule England, only to be displaced by the Plantagenets in 1154 with the accession of Henry II to the English demesnes.

However, by combining the English and French kingdoms, the Normans had unwittingly set the stage for centuries of discord over English fiefdoms in France. Henry II, the new king, for instance, was not only the Count of Anjou upon his succession, but also the duke of Aquitaine after his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. What has been termed “The First Hundred Years War” over the territories started immediately, with a peace treaty being signed in 1259 between Henry III and Louis IX of France after a century of warfare.

The One Hundred Years War began in 1293, with the confiscation of the English duchy Guyenne in France following a skirmish between the English and French navies. It was finally concluded in 1474, with the withdrawal of English king Edward IV’s forces from France and an agreement with French potentate Louis XI to settle their differences through negotiation rather than battle.

Later, the Anglo-French conflict would continue, this time over the territories of the New World and beyond. Following decades of skirmishes in North America, England declared war on France in 1756, and in 1758 the English would claim their first victory at Louisburg. What ensued was a global war between the two civilizations, with the English beating back the French in Canada, Guadeloupe, West Africa, Manila, and India in what Winston Churchill described as the ‘first world war'. Peace was brokered in 1763, with England wresting Canada and Louisiana from French hands.

The last major combat in the Anglo-French Wars were the Napoleonic Wars, which started with the elevation of Napoleon Bonaparte to the French leadership in 1799. After conquering Austria, Italy, and Germany, Napoleon turned his avaricious eyes to England, engaging the English navy on the southwest coast of Spain in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Thanks to the brilliance of English commander Nelson, who cut off the French escape with 15 warships, and Collingwood, who took over command after Nelson’s death, the English convincingly won.

Napoleon’s forces were finished off at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, when an allied army under the Duke of Wellington, consisting of Dutch, Belgian and German soldiers, with the help of the Prussians, defeated the legendary general’s 72,000 strong army at Waterloo, near Brussels. Following this final showdown, the Anglo-French wars ended after 748 years.

The Surrender of Granada, by Francisco Pradilla, representing the handing over of the keys of Granada by Boabdil to the Catholic Kings, after the Reconquista of Spain. (Public domain)

1. Reconquista

The longest war in history was the Reconquista of Spain which lasted for a staggering 781 years. In 801, after decades of Islamic rule in Spain from 718, European rulers finally started to reconquer the lost Christian peninsula following French warlord Charlemagne’s capture of Barcelona. In the north-west of the peninsula, the Christian kingdom of Asturias, which had escaped the Muslim offensive, reclaimed holdings in the 9th century, but by the 10th century a resurgence in Muslim power delayed the reconquest for another century.

The 11th century was more successful, with the lands of northern Spain being retaken by Sancho the Great who created the Kingdom of Aragon in 1035 which became a staging post for further reconquests. In 1118 Alfonso I retook Zaragoza, and in 1212 following a call to arms by Pope Innocent III, crusaders routed Almohad Emir Muḥammad al-Nāṣir, paving the way for the full reconquest of Spain.

- Warring States Period: More than 200 Years of Blood-fueled Chinese History

- Social Consequences of the Thirty Years' War: Was it Worth it?

Andulasia was the next to fall in a series of tussles between 1236 and 1248, ending in the surrender of Seville thanks to Ferdinand III, king of Castille. The Moorish kingdom of Granada, under Castilian suzerainty, was allowed to exist for financial reasons after the collapse of the economy following a poorly thought out expulsion policy of Moorish subjects by Ferdinand III. At the same time, the King of Aragon James I salvaged the Balearic Islands in 1235 and Valencia in 1238, and in Portugal Alfonso III retook Faro in 1248. By the end of the 13th century the Reconquista was mostly completed by Christians lords.

The last significant Muslim attack on Iberia happened in 1340, when Marīnid sultan Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī was bested on the battlefield by the Castilians and the Portuguese. For the rest of the 14th and 15th centuries, Aragon, Castile, and Portugal cemented their retaken possessions. With the marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, the Spanish crown was finally united, and in 1492 they drove the Muslims away from Granada, ending centuries of domination.

Depiction of a medieval battle from about 1200. (Public domain)

Never-Ending Conflict: The Longest Wars

The five longest wars in history illustrate the lengths that civilizations will go not only to achieve glory but to avenge wounds caused by conquest and invasion. John Steinbeck, the celebrated American author, viewed war as “a symptom of man’s failure as a thinking animal.” This certainly applies to the modern era, where the principles of human equality and freedom almost demand that our societies take a more enlightened stance towards cooperation. Yet in the dusty pages of history, when the world was a more violent and unforgiving place, war was a necessary evil that, if required, could last for centuries or more.

Top image: Medieval battlefield Source: Gorodenkoff / Adobe Stock

By Jake Leigh-Howarth

References

Howard, E. 2006. “The History of the Roman-Persian Wars” in History Net. Available at: https://www.historynet.com/roman-persian-wars/

Hudson, M. No date. “Battle of the Teutoburg Forest” in Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-the-Teutoburg-Forest

Lumen. No date. “The Byzantine-Bulgarian Wars” in Lumen. Available at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-herkimer-westerncivilization/chapter/the-byzantine-bulgarian-wars/

History.com Editors. 12 November 2009. “The Seven Years’ War” in History. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/france/seven-years-war

Tsouras, P. 2017. “The Cimbrian War, 113-101 B.C.” in History Net. Available at: https://www.historynet.com/cimbrian-war-113-101-b-c/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. No date. “Hundred-Years’ War” in Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Hundred-Years-War

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. No date. “Napoleonic Wars” in Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Napoleonic-Wars

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. No date. “Norman Conquest” in Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Norman-Conquest

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. No date. “Odoacer” in Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Odoacer

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. No date. “Reconquista” in Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Reconquista

Wasson, D. 2019. “Sack of Rome 410 CE” in World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1449/sack-of-rome-410-ce/

Comments

Amazing how little has changed over centuries of war other than we’re now capable of destroying all life on the planet if we carried away AND as we watch the Ukrainian invasion by Russia it is quite possible we’ll see this end result!!

From stardust I was born, to stardust I shall return

Clearly the 'SACK OF' anywhere says it all. Greed is omni present in all conflict. Not just for the plunder, but for the acquisition of slaves and right to tax the conquered. Though all this greed is well documented, it is somehow not given the importance of the conquests. Power equals money, or visa versa. This may be an oversimplification, but I think not. Conquerors do not want their ill gotten gains to be remembered for rape,murder, genocide, and theft. Instead they commission works of art and historical text to glorify their crimes, that entire cultures might worship them. Fast forward to "modern times", NUTHIN HAS CHANGED !! Today wars are planned, executed, and profited by global banksters. The right to enslave by debt servitude has been the model since the American Civil War. ALL WARS ARE BANKERS WARS. War has never been a bigger business than it is today. Neither has colonization. And propaganda. The exetential threat to civilization is not nuclear weapons, it is a handful of globalist bankers who control corporations to big to fail, politicians, scientists and generals. The idea of world domination has been sought, fought for, and lost forever. So many even today think it inevitable. But, it has never been successful, and probably won't be now either. Putin has found it's Achilles heel. He just put the Ruble on the gold standard. ALL WARS ARE BANKERS WARS.