The Achaean League’s Struggle and Beginnings of Federalism

The Achaean League was a confederation of Greek city states based on the Peloponnese Peninsula. There were, as a matter of fact, two Achaean Leagues in Greece’s history. The original Achaean League was formed during the 5th century BC but was dissolved in the following century. The second Achaean League was formed during the 3rd century BC and lasted until the 2nd century BC.

By working together as a confederation, members of the Achaean League were able to exert more political influence than they would have been able to had they operated as individual city states. Still, the league’s cumulative strength was not sufficient to save it from being conquered by Rome.

Origin of the Achaean League

The Achaean League is named after Achaea, the northernmost region of the Peloponnese. This is due to the fact that the founding members of the league were Greek city states from that region. During the 5th century BC, 12 Achaean city states banded together to form the Achaean League.

These 12 city states, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, are as follows: Aegea, Aigion, Aegira, Bura, Dyme, Helike, Olenus, Patras, Pellene, Phareae, Rhype, and Tritaeae. Originally, the league was formed to protect its members from the pirates who were raiding the Corinthian Gulf.

Territory of the Achaean League in 200 BC, excluding Boeotia. (Raymond Palmer / Public Domain)

As time went by, the Achaean League became a force to be reckoned with. This is evidenced by the fact that a number of Greek states sought to form alliances with the league. In 366 BC, for instance, Epaminondas of Thebes led an army into the Peloponnese.

As the Thebans met no resistance, they were able to march unhindered into Achaea and secured the alliance of the league. Epaminondas intended to use this alliance as a counter-weight to the Arcadian League.

The alliance between the Thebans and the Achaean League, however, did not last long, as the former began to overthrow local governments. As a consequence, revolts broke out, the Thebans were expelled from Achaea, and a short-lived alliance between the Achaean League and Sparta was formed.

The 4th century BC also saw the rise of Macedonia under Philip II and Alexander the Great. In response to the growing hegemony of Macedonia in Greece, the Achaean League adopted policies that opposed Philip.

These anti-Macedonian policies, however, were useless, as the superiority of Macedonian arms meant that Philip had no problem imposing his will on the Achaeans. Not only the Achaea, but the whole of Greece, fell under Macedonian domination.

In fact, the region would remain as such until the coming of the Romans. Around the end of the 4th century BC, the first Achaean League was dissolved by the Macedonians.

- Discovery of twenty burials in Greece may be linked to Macedonian kings

- Researchers locate Submerged Lost Ancient City where Athens and Sparta Fought a Battle

- From Mycenaean to Macedon: The Prominence of Eretria in Greek Colonization

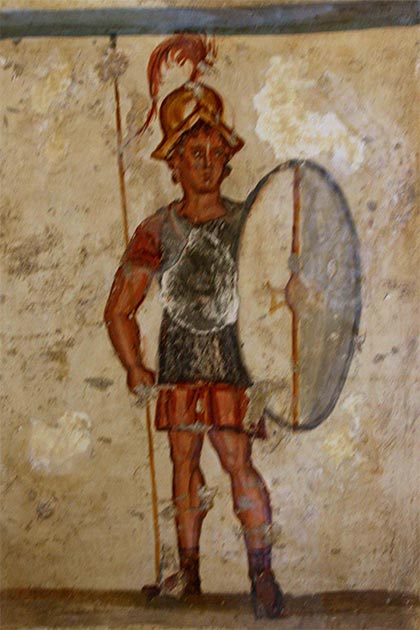

Fresco showing the superiority of an ancient Macedonian heavy infantry soldier wearing mail armor and bearing a thyreos shield. (DeFly94 / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Achaean League Reestablished

In 280 BC, the Achaean League was resurrected by some of its former members. In less than 20 years, all of the league’s surviving members were part of the new alliance.

It may be mentioned that by that time, one (two, if Olenus were counted as well) of the league’s original members had been destroyed. In 373 BC, Helike, which had been one of the Achaean League’s most important city states, was struck by a massive earthquake and submerged by a tsunami.

The second Achaean League aimed to expel the Macedonians from the Peloponnese and to restore Greek rule in the peninsula. Apart from anti-Macedonian sentiment, which was also held by the first Achaean League before its dissolution, the new league was somewhat different from its predecessor.

Unlike the first Achaean League, the second one was much more inclusive. This is evident in the fact that the members of this new league came to include city states from other regions of the Peloponnese, including Corinthia, Argolis, and Arcadia.

Consequently, the new league wielded much greater political influence than its predecessor. Polybius, a 2nd century BC Greek historian, highlights and makes an inquiry into the disproportionate influence wielded by the Achaean League, which is as follows:

“In the first place it is of some service to learn how and by what means all the Peloponnesians came to be called Achaeans. For the people whose original and ancestral name this was are distinguished neither by the extent of their territory, nor by the number of their cities, nor by exceptional wealth or the exceptional valor of their citizens.

Both the Arcadian and Laconian nations far exceed them, indeed, in population and the size of their countries, and certainly neither of the two could ever bring themselves to yield to any Greek people the palm for military valor. How is it, then, that both these two peoples and the rest of the Peloponnesians have consented to change not only their political institutions for those of the Achaeans, but even their name?”

Polybius goes on to answer his question by suggesting that it was due to the league’s equality and democratic political system that enabled it to become so influential in the Peloponnese,

“One could not find a political system and principle so favorable to equality and freedom of speech, in a word so sincerely democratic, as that of the Achaean league. Owing to this, while some of the Peloponnesians chose to join it of their own free will, it won many others by persuasion and argument, and those whom it forced to adhere to it when the occasion presented itself suddenly underwent a change and became quite reconciled to their position. For by reserving no special privileges for original members and putting all new adherents exactly on the same footing, it soon attained the aim it had set itself, being aided by two very powerful coadjutors, equality and humanity.”

Yet, Polybius was well-aware that the influence of the Achaean League did not necessarily translate to power. As the historian points out:

“Up to now, these principles of government had merely existed amongst them, but had resulted in no practical steps worthy of mention for the increase of the Achaean power, since the country seemed unable to produce a statesman worthy of those principles, anyone who showed a tendency to act so being thrown into the dark and hampered either by the Lacedaemonian power or still more by that of Macedon.”

Around the middle of the 3rd century BC, however, the Achaean League gained its chance to become a formidable force in the Peloponnese. In 251 BC, the city state of Sicyon (located in the region of Corinthia) was liberated.

A democracy was established and the city joined the Achaean League. Aratus of Sicyon, the city’s leader, became the league’s leader as well. It was thanks to Aratus’ leadership that the Achaean League became a dominant power in the Peloponnese.

Aratus of Sicyon became the leader of the Achaean League. (Leonidas1206 / Public Domain)

Apart from his anti-Macedonian policies, Aratus also endeavored to replace the tyrannies in the Peloponnese with democracies. According to the Greek biographer Plutarch, Cleinias, Aratus’ father, had been killed by the city’s tyrant while he was still a child.

Although the tyrant tried to kill Aratus, the boy managed to escape to Argos. As a result, Aratus fostered a hatred for tyrants.

In any case, Aratus fought and defeated the Macedonians on various occasions, one of the most impressive of which his capture of the Acrocorinth, or the acropolis of Corinth, in 243 BC. The city occupied an extremely strategic position in Greece, so much so that it was called the ‘fetters of Greece’ by Philip V of Macedon. The strategic value of Corinth and the Acrocorinth is provided by Plutarch as follows:

“For the Isthmus of Corinth, forming a barrier between the seas, brings together the two regions, and thus unites our continent; and when Acrocorinthus, which is a lofty hill springing up at this center of Greece, is held by a garrison, it hinders and cuts off all the country south of the Isthmus from intercourse, transits, and the carrying on of military expeditions by land and sea, and makes him who controls the place with a garrison sole lord of Greece.”

Aratus of Sicyon, leader of the Achaean League, in battle. (पाटलिपुत्र / Public Domain)

The Acrocorinth was reputed to be impregnable, due to its location on top of a steep hill and its high walls. Aratus, however, learned from some Syrian mercenaries in the citadel, that there was in fact a part of the hill where the slope was less steep and that the walls there were lower as well.

In other words, this was the citadel’s weakest spot and the best place for an attacker to make an assault. Once all the necessary preparations were made, Aratus brought 400 hand-picked men to Corinth, and successfully took the Acrocorinth from the Macedonians.

- Sparta: An Ancient City of Fierce and Courageous Citizen Soldiers

- Cleisthenes, Father of Democracy, Invented a Form of Government that Has Endured for Over 2,500 Years

- Were Catapults the Secret to Roman Military Success?

The Achaean League took the Acrocorinth from the Macedonians. (Elveoflight / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Achaean League Victories Pose A Threat

The victories of Aratus convinced more city states to join the Achaean League. At the same time, however, the league’s growing power was perceived as a threat by some, most notably the Spartans. As a consequence, Cleomenes III, the one of the two kings of Sparta, declared war on the Achaean League.

Since their defeat by the Macedonians at the Battle of Megalopolis in 331 BC, the Spartans had been keeping a low profile. Cleomenes, however, made efforts to reform Sparta, which included the revival of traditional Spartan customs, the redistribution of land, and the reformation of the army.

By waging war on the Achaean League, and defeating them in several battles, Cleomenes succeeded in turning Sparta into the most powerful state in the Peloponnese. This state of affairs, however, was not destined to last.

Aratus managed to form an anti-Spartan alliance with his old enemies, the Macedonians. In 222 BC, the Spartans were defeated by the Achaeans and Macedonians at the Battle of Sellasia.

The initial positions of the Battle of Sellasia where the Achaean League fought the Spartans. (Leonidas1206 / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Although Cleomenes had fled to Ptolemaic Egypt after being defeated at the Battle of Sellasia, this was not the end of the Achaean League’s problems. In 220 BC, the Achaeans were at war again, this time with the Aetolian League.

The war between the two leagues lasted until 217 BC and is known as the Social War. During the war, the Achaeans and Macedonians combined forces once again and defeated the Aetolian League.

Despite their alliance with the Macedonians, the Achaean League were still committed to their goal of expelling the Macedonians from the Peloponnese. An opportunity presented itself to the Achaeans when Rome and Macedonia went to war.

When the First Macedonian War broke out in 215/4 BC, the Achaean League was an ally of the Macedonians. Nevertheless, Aratus, who led the league until his death in 213 BC, kept the Achaeans out of the war. The war ended in 205 BC in a stalemate.

The Romans, however, waged a second war on the Macedonians five years later. This time, the Achaean League chose to support Rome. When the war ended in 197 BC, the Macedonians were defeated, and a ‘benevolent protectorate’ was established by the Romans over Greece.

Thanks to their alliance with the Romans, the Achaean League was in control of almost the entire Peloponnese. Even its old rival, Sparta, was forced to join the league in 192 BC. Relations between the Achaeans and Rome, however, soured as time went by.

Rome’s expansionist policy clashed with the Achaean League’s domination of the Peloponnese. During the Third Macedonian War, which lasted from 171 to 168 BC, the Achaeans entertained the idea of supporting the Macedonians against Rome. As punishment, several hostages, including Polybius, were taken by the Romans, in order to ensure that the Achaeans behaved themselves.

The Romans and the Achaean League Battle It Out

War between Rome and the Achaean League finally broke out in 146 BC. Four years before that, Andriscus, a pretender who claimed to be the son of Perseus (the last Antigonid king of Macedonia), made an attempt to restore the Kingdom of Macedonia, thereby causing the Fourth Macedonian War.

In 148 BC, Andriscus was defeated and two years later the Roman province of was established. While the Romans were kept occupied in Macedonia, the Achaean League decided to declare war on Rome in a bid to break free from Roman control. This revolt is sometimes referred to as the Achaean War.

Unsurprisingly, the Achaeans were no match for the Romans and the war was brief. The Achaeans were utterly defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Corinth. As a result, the Romans extended their rule over Greece. As punishment, Corinth was destroyed and the Achaean League dissolved.

Scene of the Battle of Corinth, the Roman legions looted and burned the city of Corinth. (Sailko / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Greece was reorganized as a Roman province only in 27 BC. The province was known as Achaea, an attestation to the supremacy of the Achaean League in the final years of ancient Greek independence. Although the Achaean League is largely forgotten, some features of its governance can still be seen today.

Members of the Achaean League enjoyed almost complete autonomy within the league’s central administration, with the exception of matters related to federal taxation, war, and foreign policy. It has been claimed that the federalism of the Achaean League, as reported by Polybius, has had an influence on the constitution of the United States and other modern federal states.

Top image: The Achaean League unified the city states. Source: matiasdelcarmine / Adobe Stock.

By Wu Mingren

References

Heritage History. 2020. Wars of the Achaean League. [Online] Available at: https://www.heritage-history.com/index.php?c=resources&s=war-dir&f=wars_achaean

Herodotus, and Waterfield, R. (trans.). 1998. Herodotus’ The Histories. Oxford University Press.

Kiprop, J. 2018. What Was The Achaean League?. [Online] Available at: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-was-the-achaean-league.html

Kosso, C., and Wilson, N. 2006. Achaea - Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. [Online] Available at: https://books.google.com.ec/books?id=8pXhAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA596&lpg=PA596&dq=Routledge+Achaea+Kosso&source=bl&ots=olMvChUKke&sig=ACfU3U2Do7uUc9WCQqgg6KOYtivUQQTTfQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwikj7LyrprpAhWkhOAKHXBpABYQ6AEwAHoECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=Routledge%20Achaea%20Kosso&f=false

McIntosh, M. 2019. The Achaean League: The Best Effort at a NATO in Ancient Greece. [Online] Available at: https://brewminate.com/the-achaean-league-the-best-effort-at-a-nato-in-ancient-greece/

Plutarch, and Perrin, B. (trans.). 1926. Plutarch, Parallel Lives: The Life of Aratus. [Online] Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Aratus*.html

Polybius, and Paton, W. (trans.). 1922-27. Polybius: The Histories. [Online] Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Polybius/home.html

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1998. Achaean League. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Achaean-League

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1998. Aratus of Sicyon. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aratus-of-Sicyon

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. Cleomenes III. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cleomenes-III

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. Macedonian Wars. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Macedonian-Wars

UNRV. 2020. The Fourth Macedonian War and the Achaean War. [Online] Available at: https://www.unrv.com/empire/fourth-macedonian-war.php

www.greekboston.com. 2020. History of the Achaean League. [Online] Available at: https://www.greekboston.com/culture/ancient-history/achaean-league/

Comments

The author this article claims “The second Achaean League aimed to expel the Macedonians from the Peloponnese and to restore Greek rule in the peninsula”. This statement implies that ancient Macedonians were not Greeks – a lie.

Ancient Macedonians were self-determined Helenes. This is witnessed by their participation at ancinet Greek only Olympiads, their standardization of Koine Greek language accross their empire, and of course the Hellenistic period where they spread Greek culture – not Slavic.

The job of historian is not to hide their national mistake of bizarrely recognizing modern Slavs as “ethnic Macedonians” – by rewriting history like a propagandist of the Soviet Union. The job of a historian is to report the facts truthfully. It is sad this alleged history website resorts to lying so the author and editors can hide their ill considered recognition of the former Yugoslav republic, homeland of as “Macedonia”.

I