“Nefer Say Nefer” - Was Nefertiti Buried in the Valley of the Queens?

She may be ancient Egypt’s most famous face, but the quest to find the eternal resting place of Queen Nefertiti has never been hotter.

Thanks to the now-iconic limestone/plaster bust of her found in 1912 at Amarna, her striking beauty and elegance have captured millions of hearts around the world. However, her final resting place has never been located, and it remains to this day one of Egypt’s most outstanding mysteries. The hunt has even attracted prominent Egyptologists such as Drs. Nicholas Reeves and Zahi Hawass, both of whom believe they may actually find the elusive mummy this year.

Ever since 2015, when Reeves first suspected there were still undiscovered chambers lying inside the tomb of Tutankhamun, possibly housing the mummy of Nefertiti, the race has been on to find what could become the greatest tomb discovery in history. Do the remains of the ancient world’s most famous woman lie concealed in the Valley of the Kings, frustratingly close to the tomb (KV62) of her nephew, Tutankhamun?

- Famed Egyptologist Proclaims Discovery of Queen Nefertiti’s Mummy

- Lady of Interest: Nefertiti Was no Pharaoh, Says Renowned Egyptologist

The Valley of the Kings. Circled in yellow, the area in which the most recent geophysical anomaly was detected in 2020, adjacent to Tutankhamun’s tomb, KV62. (Kingtut/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Or do they lie instead in the Valley of the Queens, a nearby cemetery once used for royal Egyptian women? Could the tomb of Egypt’s most beautiful and enigmatic Queen, wife of that country’s most radical ruler, be really concealed just inches from the most well-known and visited tomb in the world? Why would the burial of Nefertiti even be connected with the tomb of Tutankhamun at all?

Drama Queen

Nefertiti has become Egypt’s most famous Queen, perhaps even more famous than Cleopatra. She was wife to that country’s most revolutionary and bizarre ruler, Amenhotep IV, ruling from ~1354-1337 BC. He became an avowed monotheist and aniconist in his early years as king, and changed his name to Akhenaten in his year five. Evidence from these early years suggests that Nefertiti was just as involved in the new religious cult as her husband, and performed important duties as a high priestess to the sole new sun god, the Aten. Blocks have been recovered from their first temples at Thebes that show Nefertiti acting as priest just as much as her husband.

In the fifth year of his rule, Akhenaten founded a new city half-way between Thebes and Memphis, calling it “the Horizon of the Aten”, Akhetaten, modern Amarna. He relocated his wife, family and royal entourage and lived there for thirteen years before he ultimately disappeared. An inscription from his regnal year 16 describes Nefertiti as his “Great Royal Wife” ( ḥmt nswt wrt), but after year 17, his last known regnal attestation, events become difficult to chart as evidence becomes fragmentary.

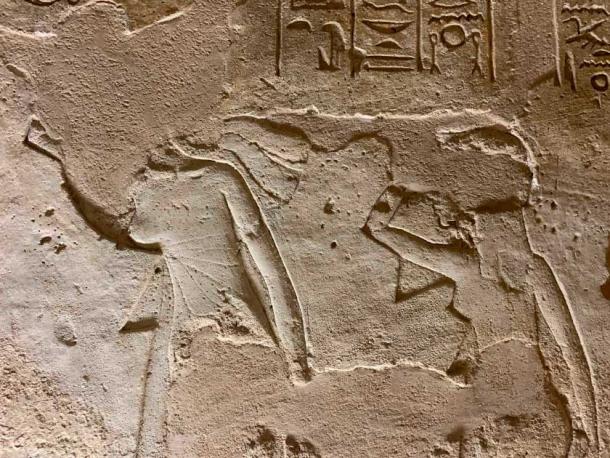

Blocks from Akhenaten’s reign, recovered at Luxor Temple. One shows the hands of Akhenaten and Nefertiti tightly clasped, a common gesture of this loving couple. (Author’s own photo)

The Royal tomb that Akhenaten had excavated for himself and his family appeared as if it was never used, and no remains of the king or queen were ever found there. This is confirmed by Amarna archaeologist Anna Stevens, who explains in her recent book Amarna (2020) that once you enter the main corridor of the Royal Tomb: “around half-way down the corridor, on the right, a doorway opens onto a long string of corridors and chambers, all unfinished and undecorated. This is the suite possibly intended for Nefertiti, although seemingly never used for a burial.”

Long Live the King

This brings us to the question: why would Nefertiti be buried in the Valley of the Kings? Well, there is good evidence that she became Pharaoh of Egypt after Akhenaten vanished, under the name “Ankheperure Neferneferuaten”. Since Nefertiti had always been known as Neferneferuaten during her years as Queen, it seemed logical that she must have assumed the throne in the wake of her husband’s disappearance. There is also evidence that she began to abandon the ultra-strict monotheist program of her husband and return Egypt to her more traditional ways.

- Nefertiti and a Rush of Scans: Race to find Double Burial Gathers Steam—Part I

- Controversy erupts as the Younger Lady is dubbed Nefertiti—Part I

Close-up of Figure 5, showing Nefertiti (left) and her eldest daughter, Meritaten. They are clearly in mourning, since they are putting dirt to their heads in the Egyptian manner to show their grief. Author’s own photo.

Egyptologist Aidan Dodson draws our attention to an important graffito from the Theban tomb of Pairy (TT139). The hieroglyphs comprise a prayer to the high god Amun, the deity previously proscribed by Akhenaten. He notes in his Nefertiti: Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt (2020), that:

“Neferneferuaten’s reign certainly continued beyond her husband’s death, as shown by a graffito dated to … Year 3 of (Pharaoh) Ankhkheperure-mery-A[…] Neferneferuaten-mery-A[…].”

The prayer was written by Pawah, a w’b priest and “Scribe of Divine Offerings of Amun”, and shows, according to Dodson: “priests of that god were once again operating openly.” It also demonstrates that Pharaoh Nefertiti-Neferneferuaten was helping to restore orthodoxy, an orthodoxy she herself had, ironically, helped to undermine with her husband only years before.

The top of the Boundary Stela A at Tuna el-Gebel, showing Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their children worshipping the sun god, Aten. (Author’s own photo.)

Tutankhamun Has a Girl’s Tomb!

Therefore, if Nefertiti became Pharaoh, perhaps co-Pharaoh with a young Tutankhamun, who was only eight when he ascended the throne, and began steering the country back toward orthodoxy, it is very likely that she would have wanted a tomb in the traditional royal cemetery at Thebes, the Valley of the Kings. Could this have originally been KV62, Tutankhamun’s tomb?

It is quite possible that KV62 may, as Dodson states: “have been Neferneferuaten’s resting place, from which she was moved when the sepulcher was requisitioned for Tutankhamun’s funeral.” This is supported by Dr. Marianne Eaton-Krauss, who argues that KV62 was not originally planned for the interment of the king (Tut), but rather that it was suitable for a lesser member of the royal family, such as Nefertiti.

This resolves the unusual feminine air to Tutankhamun’s artifacts, paintings, and tomb. Egyptologist Dr Yasmin El Shazly points out the faces on Tut’s canopic jars - used to store organs removed from the mummy in the tomb - have very feminine faces. Eaton-Krauss further argues in her The Unknown Tutankhamun (2016) that many of the items from Tut’s tomb (canopics, mummy trappings, pectorals, gold bands, etc) originally belonged to a queen who bore the epithet “beneficial for her husband” – Nefertiti’s usual title, referring to Akhenaten.

Statue of Tutankhamun on a panther, recovered from his tomb. It has been suggested, due to the feminine form, that this originally depicted Neferneferuaten, the female Queen who preceded him. (Thesupermat/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Using clues in the tomb’s hieroglyphics, Reeves told The Guardian in 2022: “I can now show that, under the cartouches of Aye, are cartouches of Tutankhamun himself, proving that the scene originally showed Tutankhamun burying his predecessor, Nefertiti.”

This corresponds with other theories that suggest Tutankhamun’s tomb was too small for a royal, and its burial chamber was built to the right of the entrance, not the left, which would indicate a queen. For example, Egyptologist Chris Naunton told Smithsonian Magazine that:

“One of the first things you notice when you enter the tomb - you come down the descending passageway and you need to take a turn right. This is quite unusual for 18th dynasty tombs because in most cases what you would expect of a pharaoh's tomb is a left-hand turn.”

The only other tomb from the 18th Dynasty involvin a right-hand turn was built for Thutmose I and re-used by his daughter, the female pharaoh, Hatshepsut. David Ian Lightbody reminds us that by the subsequent 19th Dynasty, the tomb of Ramesses II (KV7), built a half-century after Tutankhamun, also had a right-hand turn towards its burial chamber.

Throw off the Mask!

Additionally, it has been theorized by Eaton-Krauss, Reeves, Marc Gabolde and W. Raymond Johnson that the famous golden mask of Tutankhamun originally belonged to Ankheperure Neferneferuaten, probably with an epithet Mery Nefer-Kheperu-Ra, or “beloved of Neferkheperure (Akhenaten)”. Evidence includes the fact that the mask is made of many different pieces, including a front and back panel which are of different compositions. Also, some of the hieroglyphics have been re-inscribed.

Reeves demonstrated in 2015 how the present mask was likely made: a new face piece in the image of Tutankhamun was soldered and riveted in place after the original face (and earrings) had been removed. He believes this original face depicted Nefertiti, and he has even reconstructed in his article how it may have once appeared.

Non-Royal Nefertiti

Dodson comments: “given that Neferneferuaten’s burial seems to have omitted all material made for her as king, it would argue against burial in a room showing the funeral of a pharaoh. Rather, it would suggest a very basic interment, perhaps utilizing some material that had been made when she had been no more than a queen, with no attempt (or need) to provide kingly decoration in the place she was laid to rest.”

This would suggest that if she was disinterred, then she may not have been re-buried in the Valley of the Kings, but somewhere else. Reeves notes: “Had this extraordinary woman in the end been “demoted” and buried as an ordinary queen?”

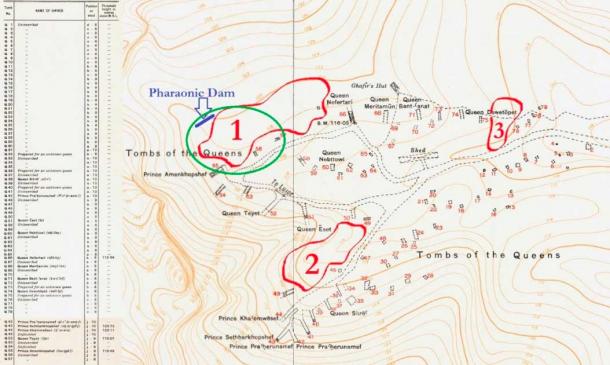

A map of the Valley of the Queens, Egypt, by Survey of Egypt (British Government) – The Theban Necropolis Sheet E-1 Tombs of the Queens. The author has identified three target areas in which to search for Nefertiti’s tomb, and has also marked the location of an ancient Egyptian-era dam built to control flooding in the valley. If flash floods were indeed occurring there, as evidenced by the dam, then perhaps Nefertiti’s tomb is still awaiting discovery right there in the western edge of the Valley, somewhere in the green circle. (Public Domain)

Supporting this idea is Egyptologist Dr. Joyce Tyldesley, who has argued that Nefertiti was never actually a Pharaoh. She has suggested that, because Nefertiti did not hail from a royal class, it would have been nearly impossible for her to assume the throne (Hatshepsut, for example, was a daughter of a Pharaoh, Thutmose I, and eligible for the throne). After the Amarna heresy, the ruling class did not likely want to remember her as a king, for several reasons, including her non-royal lineage.

This meant a big question: where was Aye, the newly declared Pharaoh, to put Nefertiti’s body? It would have been Aye’s responsibility to rebury Nefertiti, raising a further question: why was he willing to disturb the eternal rest of a monarch just to supply a tomb for Tutankhamun?

Musical Tombs under Pharaoh Aye

Most scholars have suggested Nefertiti was Aye’s daughter, but this has been disputed since there is no evidence to support it. Most likely, when Aye assumed the throne after the death of Tut, he realized he needed a tomb and that the original tomb designed for Tutankhamun, in the Western Valley of the Valley of the Kings near that of his grandfather (and role model) Amenhotep III, would actually be a perfect tomb for him! He was already elderly and needed a ready-made tomb, so he must have decided that taking over the WV23 tomb for himself and re-purposing Nefertiti’s tomb for her nephew Tut must have been the most viable and enticing option.

It is likely that the presence of Nefertiti in the Royal Cemetery was anathema to the ruling class of Egypt, since she was a) not of royal blood, 2) a woman, and 3) that Aye wished to instead remember and honour her as a Queen, wife to his nephew Akhenaten, not as a king. Could Aye and the elites have really just wanted to get Nefertiti out of the prestigious Valley of the Kings, since they were trying to steer the country back from the heresy in which it had formerly been engulfed? If true, than Aye would have wanted to rebury her in a place more suitable to what he wanted the nation to remember her as: a queen, not a king.

Since a king had to be mummified and buried within seventy days of his death, to connect him to the rebirth of the star Sirius/Sopdet, it would have been a very rushed procedure to extract Nefertiti from her tomb, re-paint the walls and texts, repurpose her artifacts for Tut and add some new items just for the boy king. This helps explain why the paintings in his tomb appear to have been rushed (there are drips of paint evident near the base of the wall decorations, and extensive mold has grown under the paint, suggesting there was no time for drying before the paint was applied).

There would have likely been no similar rush for Nefertiti, whose mummy, having already been disturbed once, could remain in a temple space until a suitable tomb and items had been prepared.

The Valley of the Queens, West Bank at Thebes, home of the famous tomb of Queen Nefertari, wife of Ramesses II. The author has identified three areas where an undiscovered tomb, perhaps Nefertiti’s, may lie - one of these is circled in red (target area #2). Could Nefertiti have been buried only a stone’s throw from Nefertari, another powerful female with whom she is often confused? (Author’s own photo.)

A Place of Beauty

The Valley of the Queens was known in ancient times as Ta-Set-Neferu, “The Place of Beauty”, and it would only be fitting for Nefertiti to rest here, since her name shares the hieroglyph nefer, or “beautiful/perfect”, and her name means “the beautiful one has arrived”. This cemetery was used early in the 18th Dynasty, two centuries before Tutankhamun, for royal woman such as queens and princesses, as well as high-ranking male nobles. The earliest tomb is QV 47, for Princess Ahmose, the daughter of Seqenenre Tao, a ruler of the late 17th Dynasty (~1550 BC).

A detailed look at the second target area in the Valley of the Queens. What could be under all of that loose rock debris in the foreground? Author’s own photo. (Author’s own photo)

According to the Valley of the Queens Assessment Report Volume 1:

“Unlike the 18th Dynasty tombs in the Valley of the Kings, which have elaborate architectural plans and are extensively decorated with funerary texts and associated images of kings and deities, those in the Valley of the Queens are without any decoration, making identification of tomb owners dependent on the finds.”

It is only with the 19th Dynasty tombs that decorations appear, suggesting that Nefertiti, who died at the end of the 18th Dynasty, may have been buried in an undecorated tomb. It could also indicate that her tomb may have been the first to include decoration, kick-starting an important trend for later dynasties. This would be in keeping with her rebel style.

The author has attempted to further narrow down where within the Valley her lost tomb might be located. 18th dynasty tombs were first plotted, followed by those from the 19th and 20th dynasties. This left three distinct empty areas where no tombs appeared: 1) at the farthest western end of the main wadi, near the gorge leading to the Sacred Grotto of Hathor, 2) in the center section of the western edge, and finally 3) between QV75 and 76 near the valley’s entrance. Further evidence was required to narrow down these possibilities: water flow data.

Looking directly at the western end of the main wadi of the Valley of the Queens, where a prominent gorge is visible. This leads to the “Sacred Grotto of Hathor”, an area of pools sacred to the feminine cow goddess Hathor (due to the gorge’s very feminine appearance in the center of the wadi). Could Nefertiti be buried somewhere in this vicinity? (Author’s own photo)

It All Comes Out in the Wash

It is now recognized that a major flash flooding event occurred in the Valley of the Kings at the end of the 18th Dynasty, not long after Tutankhamun was buried. This concealed the entrance to his tomb with rock debris, helping it avoid detection for over three millennia. Could a similar phenomenon, perhaps even the same flash flooding event, have affected the nearby Valley of the Queens, possibly hiding the entrance to Nefertiti’s tomb?

According to the VOQ Report: “a flash flood at Queens Valley will not only produce rainfall runoff, but a flow of water mixed with mud and rock debris. This has been evidenced by the substantial amounts of flood-carried sediment found in many of the QV tombs when they were cleared through archaeological investigation.”

Fascinatingly, a dam to prevent flooding was built in ancient times, and according to the VOQ Report: “At the western end of the main wadi, during torrential rains the valley of the Grand Cascade feeds a waterfall and pools of water at the Grotto Cascade, which was held sacred during the pharaonic era, and has been suggested to be the reason for the creation of a royal necropolis at this location. Below this feature are the remnants of a pharaonic-era dam apparently built to prevent flooding of tombs.”

Could Aye have chosen a location for the tomb of Nefertiti close to the gorge at the end of the main valley? Could this tomb have then been subsequently covered in flood debris and hidden? This spot corresponds to the first target identified for Nefertiti’s tomb, and the data overlap strongly suggests a possible future discovery there.

The present author wagers that the tomb of Nefertiti will ultimately be discovered in the Valley of the Queens, for as Ancient Origins contributor Natalia Klimczak reminds us: “it is very possible that more new discoveries will appear in the Valley of the Queens than in the Valley of the Kings.”

Top image: Montage showing the famous Nefertiti bust in Berlin, over images of sunrise over the Nile in Middle Egypt, near Amarna, (background), and the Valley of the Queens, West Bank, Luxor. Source: Giovanni from Firenze/ CC BY 2.0, background; © Jonathon A. Perrin

By Jonathon A. Perrin

Jonathon Perrin is the author of four books, including Moses Restored, available in print and as e-books from Amazon. His upcoming book will be a photo journey through Egypt, from Cairo to Amarna to Luxor.

Visit www.jonathonperrin.com for more.

References

Alberge, Dalya, “Tutankhamun’s burial chamber may contain door to Nefertiti’s tomb”, In The Guardian, September 26, 2022, (https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2022/sep/26/tutankhamun-burial-chamber-could-contain-door-to-nefertiti-tomb).

Allen, J.P. (2009), “The Amarna Succession”, in Brand, P. and Cooper, L. (eds.), Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane, Culture and History of the Ancient Near East Vol. 37, Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 9-20.

Balaji, Anand, “Pharaohs and Flash Floods: Was Tutankhamun’s Tomb Saved by an Act of Nature?” Ancient Origins, March 12, 2018, (https://members.ancient-origins.net/articles/pharaohs-and-flash-floods-was-tutankhamun%E2%80%99s-tomb-saved-act-nature).

Bickerstaffe, Dylan, “Tutankhamun’s tomb: How scientists solved the mystery of its hidden rooms”, In ScienceFocus, December 14, 2022, (https://www.sciencefocus.com/magazine/tutankhamuns-tomb/).

Bickerstaffe, D. (2021), ‘Nefertiti? Tutankhamen? KV62, a Tomb Under Interrogation’, KMT, A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt 31.4, Winter 2020-21, pp. 44-54.

Cross, Stephen W. “The Hydrology of the Valley of the Kings.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 94, 2008, pp. 303–10. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40345878. Accessed 21 Jan. 2023.

Dafoe, Taylor, “High-Tech Radar May Have Just Led Researchers to Discover Nefertiti’s Secret Burial Chamber in King Tut’s Tomb”, In ArtNet News, February 20, 2020, (https://news.artnet.com/art-world/discovery-burial-chamber-queen-nefertiti-1782309).

Demas, Martha, and Neville Agnew (Eds.) Project Report: Valley of the Queens Assessment Report Volume 1: Conservation and Management Planning, The Getty Conservation Institute, Aug, 2012.

D.I. Lightbody, ‘The Tutankhamun-Nefertiti Joint Burial Hypothesis: A Critique’, JAEA 5, 2021, pp. 83-99 (http://egyptian-architecture.com/JAEA5/article33/JAEA5_Lightbody.pdf).

Dodson, Aidan, Nefertiti, Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt: Her Life and Afterlife, (American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, Egypt, 2020).

Dodson, Aidan. “On the Graffito in Theban Tomb 139.” Guardian of Ancient Egypt, Studies in Honor of Zahi Hawass, edited by Janice Kamrin, Miroslav Bárta, Salima Ikram, Mark Lehner & Mohamed Megahed (2020): n. pag. Print.

Dodson, Aidan, and Stephen W. Cross, 2016. “The Valley of the Kings in the Reign of Tutankhamun.” EgArch Vol. 48: pp. 3–8.

Eaton-Krauss, Marianne, The Unknown Tutankhamun. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Factum Arte, 2015, http://www.highres.factum-arte.org/Tutankhamun/, with additions, copyright © Factum Arte/Ministry of State for Antiquities and Heritage, Egypt.

Falde, Nathan, “Famed Egyptologist Proclaims Discovery of Queen Nefertiti’s Mummy”, In Ancient Origins, September 26, 2022, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/nefertiti-mummy-0017322).

Fischanger, Federico & Catanzariti, Gianluca & Comina, Cesare & Sambuelli, Luigi & Morelli, Gianfranco & Barsuglia, Filippo & Ellaithy, Ahmed & Porcelli, F.. (2018). “Geophysical anomalies detected by electrical resistivity tomography in the area surrounding Tutankhamun's tomb”, Journal of Cultural Heritage. 36. 10.1016/j.culher.2018.07.011.

Gad, Yehia & Fathalla, Dina & Khairat, Rabab & Fares, Suzan & Gad, Ahmed Zakaria & Saad, Rama & Moustafa, Amal & ElShahat, Eslam & Mandil, Naglaa & Fateen, Mohamed & Elleithy, Hisham & Wasef, Sally & Zink, Albert & Hawass, Zahi & Pusch, Carsten. (2020). Maternal and paternal lineages in King Tutankhamun’s family.

Griffiths, Sarah, “Was Tutankhamun's tomb built for a WOMAN? The chamber's layout and 'feminine features' of the king's death mask suggest he inherited the final resting place”, In The Daily Mail, May 5, 2016, (https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3574648/Was-Tutankhamun-s-tomb-built-WOMAN-Layout-feminine-features-boy-king-s-death-mask-hint-inherited-resting-place.html).

Holloway, April, “Excitement Mounts as New Infrared Scan in Tomb of Tutankhamun Suggests Hidden Chamber”, Ancient Origins, November 8, 2015, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/excitement-mounts-new-infrared-scan-tomb-tutankhamun-suggests-hidden-020612).

Holloway, April, “Tutankhamun Death Mask was made for Nefertiti, Archaeologist says”, Ancient Origins, October 2, 2015 (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/tutankhamun-death-mask-was-made-nefertiti-archaeologist-says-004048).

Klimczak, Natalia, “Ta Set Neferu – A Valley Where Beauties Sleep – Part I”, Ancient Origins, May 16, 2016, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-africa/ta-set-neferu-valley-where-beauties-sleep-part-i-005901).

Klimczak, Natalia, “Ta Set Neferu: Tombs of the Princes and Princesses – Part II” Ancient Origins, May 16, 2016, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-africa/ta-set-neferu-tombs-princes-and-princesses-part-ii-005905).

Lidz, Franz, “King Tut Died Long Ago, but the Debate About His Tomb Rages On”, The New York Times, November 4, 2022, (https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/30/science/tutankhamen-nefertiti-archaeology.html).

Lightbody, David Ian, “The Tutankhamun-Nefertiti joint burial hypothesis: a critique”, In The Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture, Vol. 5, 2021; pp. 83-99.

Luigi Sambuelli, Cesare Comina, Gianluca Catanzariti, Filippo Barsuglia, Gianfranco Morelli, Francesco Porcelli, “The third KV62 radar scan: Searching for hidden chambers adjacent to Tutankhamun's tomb,” Journal of Cultural Heritage, Volume 39, 2019, Pages 288-296.

Manners, Gary, “Lady of Interest: Nefertiti Was no Pharaoh, Says Renowned Egyptologist”, Ancient Origins, January 24, 2018, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/lady-interest-nefertiti-was-no-pharaoh-says-renowned-egyptologist-009489).

Marchant, Jo, “Is this Nefertiti’s tomb? Radar clues reignite debate over hidden chambers”, In Nature, February 19, 2020, (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00465-y).

McDermott, Alicia, “New Evidence: Lost Queen Nefertiti May be Hidden in King Tut's Tomb!” Ancient Origins, February 23, 2020, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/king-tut-tomb-0013327).

Michaelson R., Walker P., 2016, “Tutankhamun's secret? Experts hope new chambers could contain tomb of Nefertiti,” in The Guardian, 18 March 2016.

Miller, Mark, “The Elusive Tomb of Queen Nefertiti may lie behind the walls of Tutankhamun's Burial Chamber”, Ancient Origins, August 12, 2015, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/elusive-tomb-queen-nefertiti-may-lie-behind-walls-tutankhamuns-burial-020482).

Payne, Keith, “Tomb KV64 in the Valley of the Kings: Nefertiti, Queen Tiye, or Weret-Whats-Her-Name?” In Business Trends Around the Globe, (http://heritage-key.com/blogs/keith-payne/tomb-kv64-valley-kings-nefertiti-queen-tiye-or-weret-whats-her-name/).

Reeves, Nicholas, and Peter Gremse. “The Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV 62): Supplementary Notes (The Burial of Nefertiti? III) (2020).” Amarna Royal Tombs Project, Valley of the Kings, Occasional Paper No. 5 (2020): n. pag. Print.

Reeves, Nicholas, and George Ballard. “The Decorated North Wall in the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV 62) (The Burial of Nefertiti? II) (2019).” Amarna Royal Tombs Project, Valley of the Kings, Occasional Paper No. 3 (2019): n. pag.

Reeves, Nicholas, “The Burial of Nefertiti? (2015)”, In Amarna Royal Tombs Project Occasional Paper No. 1, University of Arizona Egyptian Expedition, 2015.

Reeves, Nicholas, “Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered”, In A. Oppenheim and O. Goelet (ed.), The Art and Culture of Ancient Egypt. Studies in Honor of Dorothea Arnold (Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 19, New York) (2015), pp. 511-526.

Romey, Kristin, “It’s Official: Tut’s Tomb Has No Hidden Chambers After All”, In National Geographic, May 6, 2018, (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/king-tut-tutankhamun-tomb-radar-results-science).

Stevens, Anna, (Ed.) Amarna: A Guide to the Ancient City of Akhetaten, (AUC Press, Cairo, 2020).

The Theban Mapping Project Site, 2023, (https://thebanmappingproject.com/valley-kings).