Has Livy’s History of Rome Skewed Our View of the Early Empire?

Titus Livius, or just Livy for short, was one of the most famous historians in all of history. One of the three great Roman historians, his masterpiece, Ab Urbe Condita, made him a legend in his own lifetime. Livy covered the earliest legends of Rome through to the reign of Caesar Augustus, who died while Livy was still writing. Livy’s contribution to the historical record has been instrumental in our understanding of how the Roman people lived and how their empire was created. Here is everything you need to know about one of history’s greatest historians.

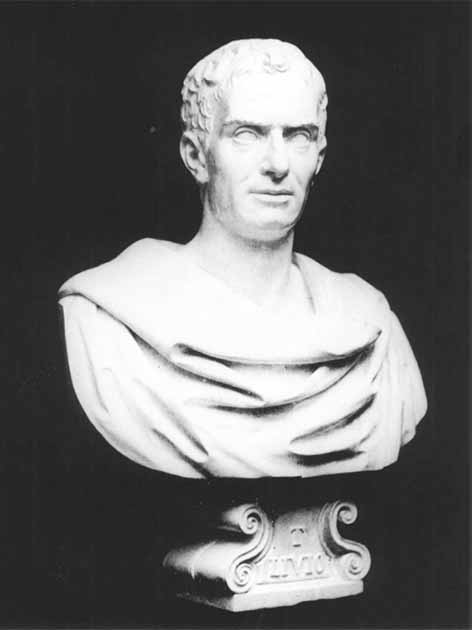

Titus Livius statue at the Austrian Parliament Building in Vienna, Austria. (Acediscovery / CC BY 4.0)

The Early Life of Livy

Although Livy would spend much of his life living in and writing about Rome he was actually born in 59 BC, in Patavium, a town in modern Padua. While small compared to Rome, it was a wealthy town and the second largest in the province of Cisalpine Gaul in northern Italy.

While not initially part of Roman Italy, during Livy’s life, Julius Caesar brought the whole of Cisalpine Gaul into the Roman fold, giving all residents Roman citizenship. Livy was both a proud Roman citizen and a proud Patavium native. The town's traditional, conservative values heavily influenced his later writings.

- Thucydides: General, Historian, and the Father of Scientific History

- Herodotus, Cato the Censor and Josephus: Understanding the Life and Times of Historians of the Ancient World

Pratum vallis Patavii, near Livy’s birthplace (Didier Descouens / CC BY SA 4.0)

Growing up in an affluent town did not make Livy’s life free of drama. He was unlucky enough to grow up during a series of civil wars that threatened to tear the Roman Empire apart. His hometown was caught up in these wars when the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, Asinius Pollio, took the side of Marcus Antonio, a leader of one of the warring factions, against the Senate. The people of Patavium refused to betray the Senate and would not contribute their wealth to the governor or his chosen side.

Pollio responded by attempting to bribe the citizens’ slaves into betraying their masters. The slaves, too, refused. The people of Patavium stood together in supporting the Roman Senate. This all meant that Livy was unable to go to Rome for higher education or tour Greece, as most young noblemen did during this time.

Instead, he received his education in his hometown. He spent his time writing short historical biographies and philosophical works, biding his time until the wars ended and he would be able to leave his hometown.

Besides this, not much else is known about Livy's early personal life. We know that at some point he got married, having one son and a daughter. We know nothing about his parents, except that they were of a high social class but not senatorial.

- The Seven Hills of Rome: Center Stage in Rome’s Eventful History

- Bards, Historians And Historiographers Of Ancient Greece

A bust of Livy, celebrity historian of Rome (Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti / CC BY SA 4.0)

Livy’s Time in Rome

It is believed that Livy finally traveled to Rome at some point during the 30s BC. It seems likely that after arriving, he spent a lot of time in the city, but we do not know if it was his primary residence or if he split his time between Patavium and Rome.

While in Rome, Livy never served as a senator or held any kind of government position. His habit of making basic mistakes when writing on military matters indicates he probably never served in the military either. Unlike most Roman historians of the time, he assumed the role of full-time historian, something his contemporaries criticized him for.

It would not have been easy for Livy to live a comfortable independent life as a full-time historian. There is no record of Livy relying on a donor, so it's believed he must have inherited considerable wealth from somewhere, although the source is a complete mystery. Emperor Augustus was fond of the fact that Livy did not rely on a patron, noting that it meant Livy didn’t really care who he upset.

Livy’s History of Rome ( Ab Urbe Condita)

Livy’s independence from any specific patron allowed him to focus on his magnum opus, his History of Rome. While we cannot be certain, historians believe he began the work when he was around 32 years old, after having moved to Rome. The work was a lifelong project, and he was still writing it when, as an old man, he finally left Rome and moved to Padua during the reign of Tiberius (14-37 AD). The final books of the History of Rome were published posthumously.

He began the project by writing and publishing in units of five books. Each book’s length was dictated by the size of the papyrus roll. He ended up abandoning this approach as his work became more complex. It is believed he ended up writing a total of 142 books, most of which have been lost. Today, books 11-20 and 46-142 have never been recovered.

The writing of the books became an obsession for Livy. He averaged around three books a year. In a letter, Pliny the Younger, a famous Roman author, recollected that Livy had told him he was tempted to give up on his work, but his fascination wouldn’t allow it.

The early books cover the founding of Rome and the sacking of the city in 390 BC, while the later books cover 29 BC to 9 BC. Thanks to summaries and fragments quoted by other historians and authors, we know roughly what the missing books covered, but lack exact details.

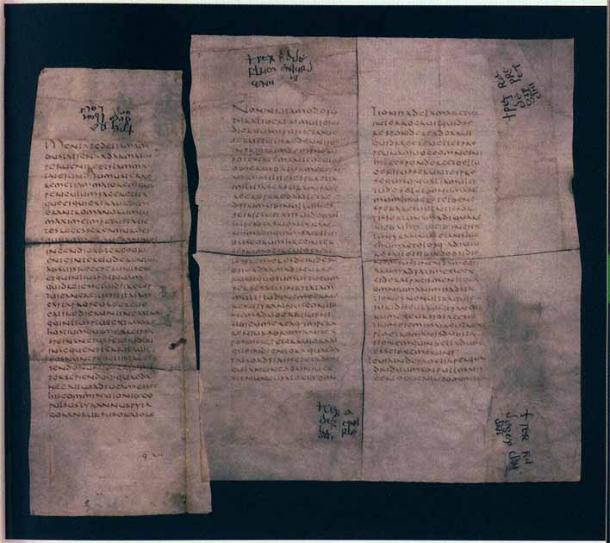

Fragment of a 5th century copy of Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita Libri, held at the Vatican (Public Domain)

Livy’s Approach to History

Livy wasn’t the first Roman historian to attempt a comprehensive history of Rome. The Romans had been at it for over 200 years, with the first Roman historian being Quintus Fabius Pictor.

In Rome, historians usually had two primary motivations, which were often intertwined. The first was a genuine antiquarian interest. As Rome became older, especially after 100 BC, there was an increased interest in the early days of Rome. People wanted to know about ancient ceremonies, religious customs, and the genealogies of prominent Roman families. In short, the Roman people were interested in where they had come from, and were proud of their shared history. This curiosity surrounding family genealogies often had a political side. For example, there were attempts to attach the family heritage of Julius Caesar to that of the legendary Trojan warriors.

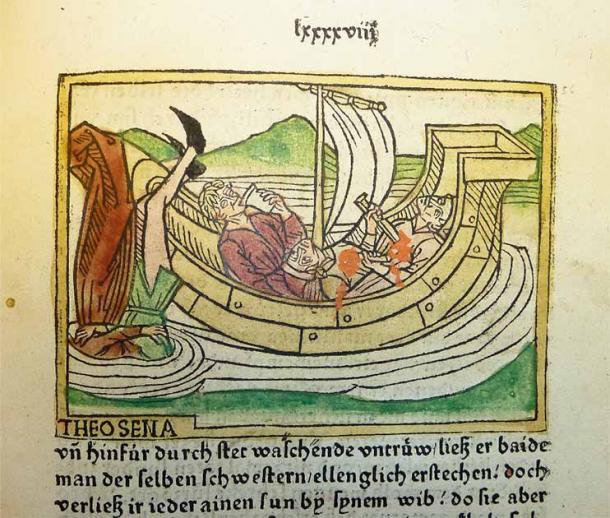

Woodcut illustration circa 1474, of the death of Theoxena, her husband Poris, and his children, as recorded by Livy more than 200 years after the event (Public Domain)

Most historians were public figures who held some kind of office. For example, Quintus Fabius Pictor was an ex-praetor, a high-level official; Cato had been a consul and a censor, and Sallust was a praetor. Rulers such as Sulla and Caesar often acted as amateur historians in their leisure time. In an attempt to justify his actions, Caesar wrote the Gallic War and Civil War. These prominent historians had a tendency to use history as a way to explain, or excuse, their present.

Livy, however, was different. He had never been in the military and had no interest in holding public office. He was driven by a pure passion for history. He was free from political bias and had no benefactor breathing down his neck.

This should have been positive, but it did come with some drawbacks. Livy’s exclusion from the senate meant he had no real-world experience of how the government worked on a day-to-day basis. This lack of knowledge showed itself occasionally in his work. The same can be said about his lack of military experience, which led to some basic errors in his understanding of military matters.

His lack of political access also left him unable to use primary documents, like senate meeting minutes, the texts of treaties and laws, and more. He lacked access to important political materials that would have helped him explain history in political terms.

Instead, Livy wrote about Roman history in personal and moral terms. In his preface, Livy laid out his belief that Rome was experiencing a serious moral decline. His masterpiece was an attempt to show his fellow Romans how far Rome had fallen from its glory days.

Rather than recording history through partisan politics, Livy focused on the morals and personalities of those in power. His work is full of pointed and revealing comments, and Livy never shied away from saying what he thought.

Livy wasn’t the only Roman who viewed history through a moral lens. Indeed, the most prominent Roman, Augustus, did the same. During his reign, Augustus brought in legislation and propaganda that he hoped would encourage a return to old Roman ideals.

It is no wonder that the two men grew close. Livy spent much time with Augustus and the royal family. Whether or not the two could be described as friends is unclear. It is clear Augustus respected Livy’s love of the old Republic and referred to the historian as Pompeian as a mark of respect.

The Roman historian Livy spent a lot of time with Emperor Augustus (Stellc9732 / CC BY SA 4.0)

The downside to Livy’s moralistic approach was that he wasn’t always the most accurate scholar. If he had a moral point to make, Livy was not opposed to bending the facts to suit his needs. Livy has often been criticized for not being an original researcher. He had a tendency to take what those who had come before him had written and shape it to fit his needs. This led to accusations that he was less of an academic and more of a writer.

On top of his poor understanding of military and political matters, his geography wasn’t much better. He also struggled with learning Greek. Despite these technical flaws, Livy’s writing was often seen as top-class. He was an engaging writer, skilled at making history interesting. That is, unless one were to ask Emperor Caligula, who derided Livy’s work as poorly written and without merit.

Receptions to Livy’s Work

Some of Livy’s musings may have proven to be controversial, and not everyone was impressed with his methods, but Livy’s work was a major commercial success. His History of Rome was in heavy demand from the time it was first published until his death. Livy became a celebrity in his own right, and people would travel from all over the empire to visit him and see him work.

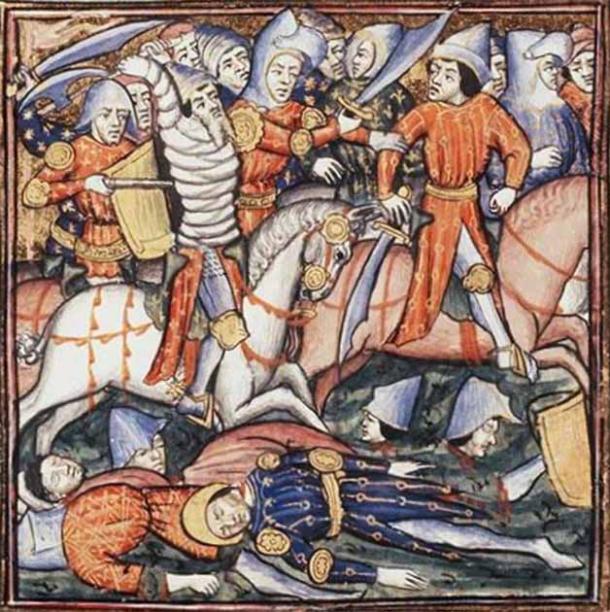

Depiction of the Battle of Cannae, based on Livy’s History of Rome, circa 1400 (Public Domain)

While some historians criticized his moralistic approach and technical shortcomings, his work was a major source of information and inspiration for later Roman historians. His work was influential enough that, following Augustus's death, Livy’s work had a major effect on Emperor Claudius, who enjoyed writing histories in his free time.

Livy’s work remained popular well into the Middle Ages. Sadly, the sheer length of his books meant that by this time, the literate class had grown tired of reading the originals and had opted for reading summaries. As a result, during this time, the original manuscripts were lost and never replaced, the summaries being easier to read and store.

During the Renaissance, there was a realization that Livy’s originals were being lost to history and intellectuals spent vast sums attempting to preserve what was left of his work. Unfortunately, it was largely too late.

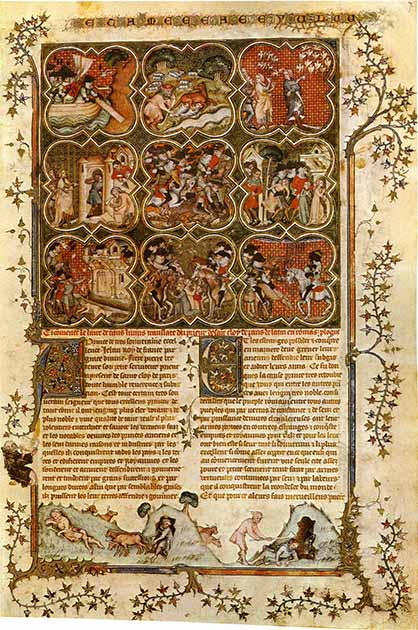

An illumination in a 12th century manuscript of Livy, Ab urbe condita, in the French translation of Pierre Bersuire. The manuscript belonged to King Charles V of France. The illumination shows mythical scenes concerning the foundation of Rome and previous mythical history. (Public Domain)

Conclusion

It is a shame that so much of Livy’s work has been lost. All we have left are a few short fragments of his work, and summaries written by his peers and successors. Livy’s work was enormously instrumental in shaping future understandings of the history of Rome, and we owe much of what we know today to him.

However, this didn’t stop later historians from criticizing him. Much of this criticism was well-earned. Livy didn’t always value accuracy, often preferring to make a point than state an accurate fact. This is a slippery slope for a historian. He also tended to embellish Roman history and exaggerate the moral fortitude of early Roman leaders, in an attempt to highlight more modern shortcomings.

Still, we should not criticize the man too harshly. Livy did what all great historians strive to do, bring history alive for his generation, so that it is not forgotten. Livy had experienced the horrors of the Roman civil wars as a young man and hoped his works would help avoid other such wars. As a historian, he knew that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

Top Image: Montage of Roman Empire imagery including statue representative of Livy. Source: Freesurf/Adobe Stock

By Robbie Mitchell

References

Chaplin, J. 2000. Livy’s Exemplary History. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://archive.org/details/livysexemplaryhi00chap/page/n3/mode/2up

Livy. circa 9 BC. From the Foundations of the City.

Mellor, R. 1999. The Roman Histories. Routledge.

Ogilvie, R. M. 1998. Livy. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Livy/Livys-historical-approach

Wasson, D. March 17, 2014. Livy. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/livy/

Comments

How hard or easy would it be to create a fictitious ancient historian in order to further divert from the truth? Just sayin'.

Nobody gets paid to tell the truth.